Someday, My Father Will Die. Today, We Are Enjoying Lunch Together.

As my dad faces health challenges, it makes me wonder: Have I valued him enough? Have I shown it?

On Wednesday, two days after a leisurely lunch with my father, my mother called. Her voice was tense and tight. "I'm on my way home — Dad is throwing up, he said he is feeling lightheaded. It's probably just heat exhaustion. You know, after his bike ride."

My dad is an avid cyclist, and he is also 76 years old with a history of cardiac issues. I said, "Take him in! Or call an ambulance. It could be a heart attack." She ended the call with a soft goodbye, and then I waited to hear what had become of my father.

On Monday, two days earlier, I'm with my father at one of his favorite Minneapolis restaurants. Our table overlooks the vastness of Lake Minnetonka and the sky is as blue as I've ever seen it. It is seventy-four degrees and sunny, as beautiful a day as they come.

I sit down in the wicker chair next to my father. He has the glow of a summer tan and looks at home in his collared shirt and sunglasses. His gray curls are just so. "Hi Dad," I say, as I lean over to give him a hug.

Since my daughter Eden was born with a rare genetic deletion, my father has delivered more meals to my family than I could ever count; he often brings dinner multiple times a week.

The breeze rolls through our table and feathers our hair as if we are on vacation. We talk about various life transitions, getting older and his upcoming move to a condominium with my mother. He is leaving my childhood home, his home of 39 years. As we talk, I feel him all there. This is a remarkable trait in a human.

Our Regular Lunch Dates

Throughout most of my adult life, my dad and I have kept a regular lunch date. We used to do weekly restaurant outings, which were almost always a delight. We had some laughs, some conversation about the world, our lives and where we were headed. And since my daughter Eden was born with a rare genetic deletion, my father has delivered more meals to my family than I could ever count; he often brings dinner multiple times a week.

I know I am incredibly lucky to have a dad who is magnanimous with his time, affection and every resource that he and my mother have. He is the kind of person who gives freely, without scorekeeping or expecting something back in exchange.

"Thank you for being so planful," I say. "You've always been so thoughtful about the future." I look at his crinkled brown eyes, bright with love, yet also with a fatigue that I've noticed has increased over time. In that moment I felt the weight of the past, this sparkling moment, and most of all, the uncertainty of the coming years.

I fill him in on my daughter Eden's recent antics, which are always slightly unbelievable. Since Eden's birth, we haven't had as many lunches out together. She lives on a feeding tube and has severe ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder). Her disabilities require around-the-clock care, and care for her is hard to find. It's not easy for me to leave the house, let alone sit around midday to shoot the breeze.

I feel guilty that I have had less time with my dad since Eden was born. And I want to enjoy the hours that we have now. Sometimes I can, and sometimes I long for it, yet the moment feels just out of reach, a box on a shelf that is just too high, even when I stand on my tip toes. I don't know if he knows any of this, my awareness, my hankering.

But the mood between us today is light, and I go with it. I take a bite of bright green avocado from my plate, I look around at the waves lapping up at the shore. I dive into an emphatic story about Eden's deep feelings for the K-Pop group BTS. As I gesture at her dance move, I jut my right hand expressively — smack into my iced tea. The amber liquid cascades over our table. I hear the ice hit the ground with a thin clank.

"Good spill," my dad says lightly. "It didn't even get on your clothes." As I sop up the mess with my cloth napkin, I think about how accepting each other's mistakes is one of the best things we can do.

A Thread of Mutual Appreciation

Taking him in, I see the past more clearly. Back when I was growing up, my father was the primary earner in our family. He had a high-pressure job running a business in the restaurant industry and traveled frequently. My mother did much of the heavy lifting of parenting. One year in the annual family holiday letter, she gushed that I had learned to talk in sentences, including, "Where's daddy?"

Of course, our relationship hasn't been perfect, yet we have settled into an understanding of each other that comes with age. And sometimes, a healthy dose of individual therapy.

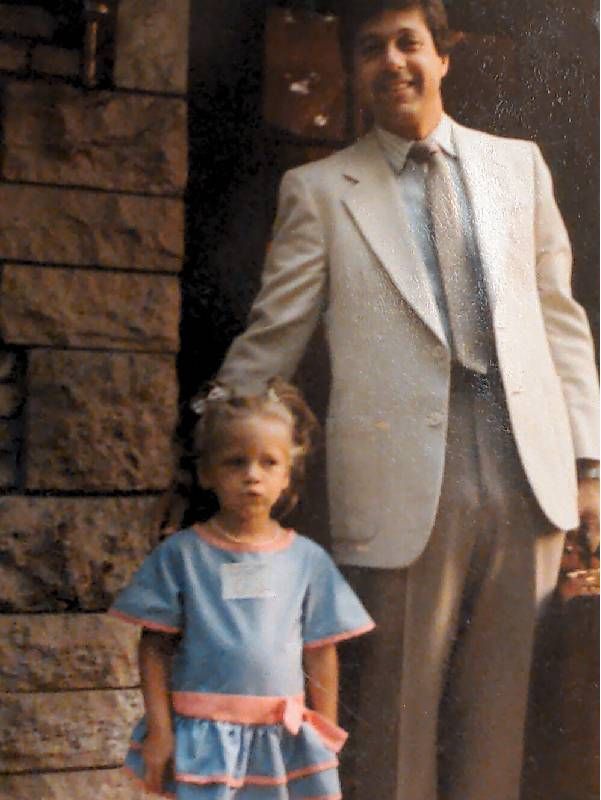

Regardless, my father and I have almost always carried a thread of mutual appreciation. When I was a child, he took me to Mr. Donut in his ruby colored Cadillac every Friday morning on the way to school, and as we sat at the counter together, the rest of the world faded away; all that existed was sugar, flour, butter, and my dad.

Even back then, he asked me for my opinion on things like restaurant policies — I helped him read his customer comment cards. When I offered suggestions about what to do about this complaint or that one (I was nine), he seemed to take my ideas seriously. My father talked to me like what I had to say mattered. He still does.

Even in lighter times, my father talks about death the way some people talk about the Mets —casually and often.

On the afternoon my father is admitted to Abbott Northwestern hospital, my husband Cedar and I wind around the windowless corridors and find him in an adjustable bed, hooked up to chirping monitors, looking still and quiet. After several days and a robust battery of tests, the team of doctors decides that he does not need a stent after all. Thankfully, he leaves with a best-case scenario, a medication adjustment.

A few weeks later, my father lands in an ambulance due to his skyrocketing blood pressure. Again, after fluids, testing and additional adjustments to his med regimen, he is well enough to return home. But I am reminded again of the tentativeness of his health.

I knew that he wouldn't always return to the house that I grew up in, to the life that he knew. My dad has always been so active — in fact, he is a ridiculously vital person — with spin classes and weight-lifting regimens and world travel. Yet it is clearer now than ever, he won't always be this way. He won't always be around.

Facing the Reality Ahead

Even in lighter times, my father talks about death the way some people talk about the Mets —casually and often. When referring to taking a risk, one of my dad's favorite sayings is, "How long are you going to be dead for?" He isn't always so flippant; he and my mother also consider the last chapter their lives carefully, meticulously preparing their health care directives and updating them regularly. I receive new copies in my inbox with subject lines such as Revised 5th Season Thoughts, as if we are planning a leaf peeping trip to Vermont.

But now it feels more real. There is something about the hospital that evokes a seriousness, a finitude. I have watched over my daughter during many harrowing hours in our local children's ward, wondering if she will make it to her fifth birthday or tenth or fifteenth. I am no stranger to the possibility of losing the most beloved.

When I think back to that idyllic lakeside lunch with my dad, I am acutely aware that it could have easily been our last.

As I consider my father's mortality, I wonder how will I ever live without him? What will my days and weeks be like when he is gone, when I can no longer call him for advice, for a chuckle, for anything at all? How will I handle the inevitable onslaught of grief when both of my parents have passed, and I will face this world in many ways, on my own? How do any of us continue to move forward when our parents are gone?

When I reflect on this, it makes me wonder: Have I valued my dad enough? Have I shown it? Does he know that I see how deeply he has been there for me, supporting building a foundation of love so steady that I never once questioned that basic core fact?

I know that I don't have the answers to these questions, and I also know that my father will always be with me, even when he isn't physically here anymore. And while I still can, I plan to sit down with him whenever possible. Yes, just like anyone else, it's easy for me to feel like I'm too busy, that my to-do list is too long to include something that might appear optional, or even frivolous. Yet what I want to give to the people I most love is what I also want to receive — presence. The thing my father has always offered to me.

When I think back to that idyllic lakeside lunch with my dad, I am acutely aware that it could have easily been our last. For this, and countless other meals we have shared, I am grateful. Grateful and still, sometimes afraid, all too aware of the precariousness of our time together. And yet, another way to look at it is this: these complex feelings mean that I am still alive. And miraculously, so is my father. Which means we still have time left to spend together.