Spinal Stenosis: A Painful and Frequently Misdiagnosed Condition

As we get older, this common back problem can get worse. Here's how to recognize the symptoms.

For a decade, starting in his early 50s, John Stanton felt as though he was walking on hot, burning coals. His ankles ached and throbbed, his feet were always tingling and, at times, all his toes felt as if they were being cut with glass.

"For years doctors told me that these sensations were caused by arthritis, both rheumatoid and osteo," says Stanton, a magazine editor who asked that his real name not be used. "To ease the pain, I took Aleve, which helped a little. But as the years went on, the pain became more constant. I felt it more intensely at night, making it hard, if not impossible, for me to sleep."

Stanton also spent 10 years undergoing twice-yearly epidural steroid injections in his lower back that would send cortisone coursing down his legs and to his feet. The shots helped, but they didn't alleviate the condition altogether — and as time went on, their soothing effect lasted for shorter periods.

"I didn't know what to do," says Stanton, who recently moved from Boston to Minneapolis. "I didn't want to go every few months for shots and I certainly didn't want all of those steroids in me."

Discovering the Real Cause of Pain

Looking for another possible solution, Stanton booked an appointment with a neurologist in Minneapolis. After undergoing an MRI, he learned that arthritis, though it existed, was not the primary culprit of his pain. It was due to compression of the spine—a result of the natural aging process. The pain he had been experiencing for a decade was caused mainly by a problem in his lower back called lumbar spinal stenosis.

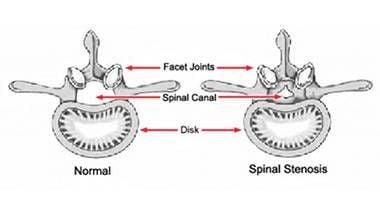

Spinal stenosis is one of the most common back problems of middle-aged and older adults. It involves subtle — and sometimes, not so subtle — narrowing of the vertebral canal that houses the spinal cord, most commonly in the lower back.

"I'd be jumping out of bed every few hours. My social life was suffering, too."

As the nerve roots connected to the spinal cord, or the cord itself, are squeezed, communication between brain and body get distorted or disrupted, so that the brain perceives impulses originating at the site of stenosis as pain signals from the legs or feet. Numbness or muscle weakness can ensue. It can also spark paresthesia, the pins-and-needles discomfort or burning sensation that plagued Stanton's legs and feet.

"Patients with lumbar spinal stenosis often report pain while standing or walking," says Stanton's current neurologist, Mark E. Labenski of Northfield, Minn., the third of three neurologists Stanton consulted in Minnesota. "Their pain is usually alleviated by leaning forward, sitting or lying down."

When spinal stenosis compresses the spinal cord in the neck, symptoms can be much more serious, including crippling muscle weakness in the arms and legs or even paralysis.

The Causes of Spinal Stenosis

It may be a common problem, but spinal stenosis often goes undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. The symptoms are frequently dismissed as part of the aging process, but they should not be ignored. Chronic pain is debilitating. Depending on its cause, stenosis can be progressive, getting worse with time.

"At my last job, it was really hard to work," says Stanton, who points out that he eats right and stays physically fit. "Sometimes when I got up from my desk, my legs would give out and I'd collapse. The condition was rapidly getting worse. Besides the burning pain, my shins and ankles were starting to cramp, especially after I'd fall asleep at night. I'd be jumping out of bed every few hours. My social life was suffering, too. When I'd go to a movie, I'd have to get up and walk around. I couldn't sit long in one position."

There are many causes of spinal stenosis. Spondylitis — inflammation of the body's joints and vertebral tissues — is a common culprit. With age, the cushioning discs between vertebrae can become tattered, a condition known as degenerative disc disease or spondylosis, or discs can herniate or slip out of place.

Subscribe for More Health News

Next Avenue covers the full spectrum of aging, including your health. Subscribe to our newsletter to get articles like this delivered to your inbox.

Bony growths within the spinal canal can also crowd the spinal cord over time. Among older adults, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis of the spine are often associated with spinal stenosis, and in rare cases, spinal tumors. And, of course, falls and accidents can cause back injuries that result in spinal stenosis, as can new bone growth associated with healing after subtle fractures.

More Studies Needed for Treatment

Because symptoms vary from patient to patient, diagnostic medical imaging is crucial, Dr. Francisco Kovacs says.

"To establish the diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis, two criteria have to be met," says Dr. Kovacs, director of the Spanish Back Pain Research Network in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. The patient has to report pain down the leg "and a CT scan or MRI must show that the narrowing of the lumbar canal is compressing the nerve, which corresponds to the anatomical distribution of leg pain," he says.

Clinicians have tried myriad treatments to offer patients relief, but convincing evidence of a proven treatment has been elusive. A recent look at data from 21 clinical studies involving 1,851 patients found only "low quality" or "very low quality" evidence for pain control and improved walking from pharmacological interventions like calcitonin, prostaglandins, gabapentin, methylcobalamin or epidural steroid injections. Evidence is so sparse, the authors say, that specific clinical guidelines cannot yet be recommended. The report also concluded that large, well-designed clinical studies are "urgently needed."

The benefits of spinal or nerve root decompression surgery or the fusion of adjacent vertebrae are "probably marginal," and the effectiveness of intra-discal electrotherapy (IDET), a popular treatment, "remains unproven," according to a 2008 review of the scientific literature by the Cochrane Collaboration.

The Condition Becomes Worse

After visiting his first neurologist in Minneapolis, Stanton underwent a new round of steroid injections — one targeting each leg. "This time the relief only lasted for three days, so I knew I couldn't continue treating my problem with shots," he says.

"I didn't know how mentally and physically exhausted I'd been from the spinal stenosis until I completed the therapy."

This neurologist who gave him the injections told him the time had come for surgery to relieve pressure on the spinal cord and nerve roots. "He held up an X-ray and showed me the inflammation in my spine," Stanton says. Seeking a second opinion, Stanton visited another neurologist, who also said the time had come for surgery. Both the first and second neurologist told Stanton they couldn't guarantee that surgery would be successful. Or how long recovery would take.

"I have a very enlightened GP," Stanton says. "When I told him I had visited two neurologists, both of whom recommended me going under the knife, he said to me: 'Not until you talk to my colleague, Dr. Labensky; he believes in physical therapy for back problems. He'll only recommend surgery if there's no other solution.'"

If you receive a diagnosis of spinal stenosis, Stanton recommends asking your doctor about physical therapy options. He also suggests enlisting the aid of a personal trainer who can put together a back strengthening routine for you at your health club. The National Institute of Health suggests acupuncture and chiropractic as possible non-surgical options. According to the NIH, possible indications for surgery: symptoms that get in the way of walking, problems with bowel or bladder function, and problems with your nervous system.

After consulting Dr. Labensky, Stanton agreed to undergo three months of physical therapy two to three times a week. "I was told this routine works for 90 percent of people with spinal stenosis," Stanton says. "It gets them out of pain and on with their lives."

The therapy, conducted in a hospital clinic, uses Nautilus-like exercise machines to strengthen back and leg muscles. Back exercises help with stenosis and leg pain by working on the soft tissue component of spinal stenosis. "Most patients also have some disc disease, either bulging or frank herniation," Dr. Labenski says. "When this occurs the disc almost always, due to anatomy, pushes posteriorly into the spinal canal, worsening the spinal stenosis."

Strengthening spinal extensor muscles takes pressure off the disc because stronger muscles can handle more of the body weight that discs otherwise absorb, he says.

"Exercise is an evidence-based option for common back pain," Dr. Kovacs agrees. But, he cautions, clinical trials have not been convincingly conclusive. "The available evidence is not enough to affirm its effectiveness on scientific grounds."

How Exercise Worked in This Case

Stanton, however, says he doesn't need to see any scientific papers. "It worked," he reports. "But it wasn't easy therapy. It was really intense. For one exercise, I was strapped into this medieval-looking lower-back machine, like something from a torture dungeon. I had to use my legs and torso to push backwards for 30 reps. The therapists started me with 70 pounds and over three months worked me up to 185 pounds."

By then, "the burning and cutting sensations were practically gone," Stanton says. "My body felt strong and I had energy. I didn't know how mentally and physically exhausted I'd been from the spinal stenosis until I completed the therapy."

But as Stanton found out, therapy isn't something you can just walk away from. "For a few weeks after I completed the therapy I didn't do much. I wasn't doing my at-home back exercises or stretching. And the pain started coming back."

On the advice of Dr. Labenski, Stanton joined a health club — most have Roman horses and other back-strengthening equipment. "It's a big commitment, but I try to go to the gym every day," Stanton says. "The pain is 90 percent gone again. Working out beats being in constant pain — and it sure beats back surgery. Plus, it just feels good to be in shape again. It's amazing how the body can heal itself. I feel years younger."

When conservative approaches like exercise therapy do not work, however, surgery remains the most frequent treatment. Techniques vary and success rates have not been systematically studied, making it difficult to compare outcomes. If patients have sudden loss of strength in one or both legs or lose feeling in their upper, inner thighs or groin, surgery should be seriously considered, Dr. Kovacs says. For patients with vertebral slipping, spinal fusion should also be considered, he adds.

"If the pain ever becomes as intense as it once was, I would consider surgery," Stanton says, "but for now I have my spinal stenosis on the run. I just wish I'd known 10 years ago what the cause of my pain was and where it was really coming from. All those years I was afraid to do intense exercise for fear of worsening my condition — but it's what I needed to do all along."