A Former Playboy Employee Remembers Hef

Working for Christie Hefner colored this feminist's experiences at the company

As a self-avowed feminist not known to mince words or tolerate much from men behaving badly, there are few things I’ve uttered in my life that stopped conversations faster than, “when I worked at Playboy ...”

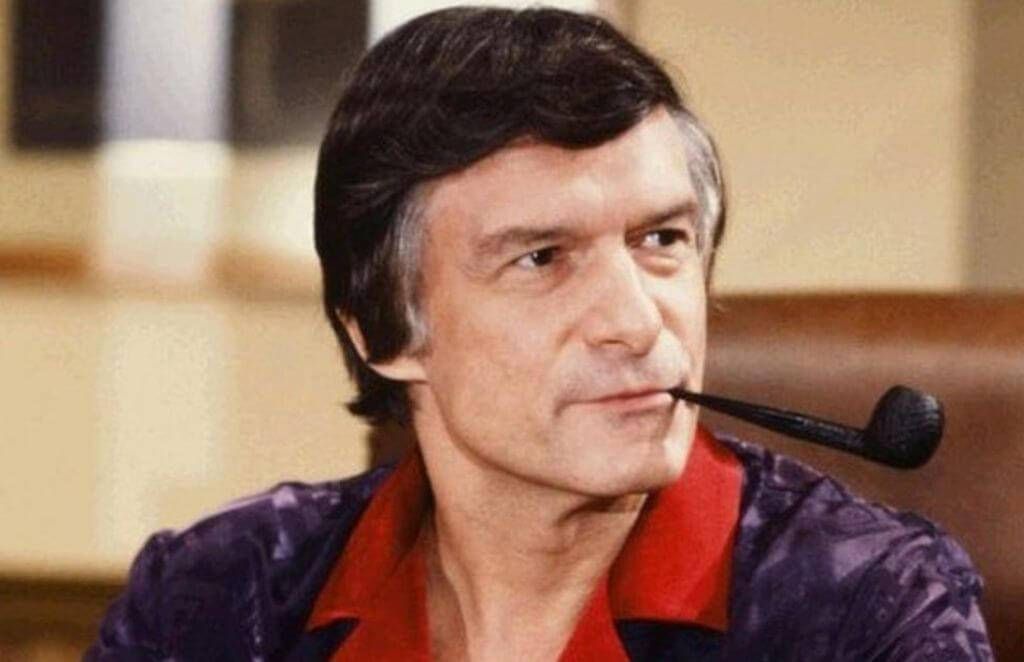

So perhaps it’s not much of a surprise that although I left the House that Hugh Hefner Built more than 17 years ago, his death last week at 91 left me unsettled and reflecting on the influence that Playboy, and by extension, Hef had on my life. Commentary in the last few days tackled the question of whether Hefner empowered or exploited women. The answers have ranged from excoriating (The New York Times) to more expansive (Politico).

As with most notable American figures and institutions, the question is not one that can be easily or patly answered. My experiences at Playboy and their lasting impact had little to do with Hugh Hefner as an individual. (My communications with him consisted of a handful of memos and missives from his more trusted lieutenants.) The significance of my time there instead had everything to do with what Playboy personified to a young woman growing up in the Deep South when Playboy was as its heyday, and with Hefner’s oldest child, Christie, an extraordinary woman with whom I worked on a near-daily basis for the four years I was with the company.

Playboy as My Tool of Reinvention

Hugh Hefner was fond of referring to the times in his life during which he “reinvented” himself — beginning in high school when his first romantic crush chose a friend over him, then in his early 30s when he became the human embodiment of the Playboy brand, and again in his 80s, after his second divorce, when he re-entered the national zeitgeist with three 20-something girlfriends and a hit TV reality show.

Just as it had with Hugh Hefner, Playboy figured prominently in my own reinvention. After early career disappointments and a failed first marriage, I left my city, my job and my dog and returned to graduate school in Chicago. After graduation, I was anxiously looking for a full-time job, barely paying the bills by working at an ill-suited, part-time position with a medical device manufacturer. My university, Northwestern, connected me with a professional mentor who was married to longtime Playboy executive Martha Lindeman, one of the scores of women in the company’s managerial ranks. Playboy was looking for a new director of corporate communications; would I be interested? Although I had worked as a newspaper reporter for 10 years — skills a publishing company like Playboy would no doubt appreciate — my graduate degree in marketing communications and seven months in an entirely unrelated industry in my new field didn’t seem to qualify me for the Playboy position.

But I was bright, quick on my feet, wrote exceptionally well and was fascinated with the pop culture themes that Playboy excelled at chronicling. Lindeman and her boss, Playboy’s Chairman and CEO Christie Hefner, took a chance and hired me. I was 34.

Playboy as a Rorschach Test

Christie Hefner has said over the years that people’s impressions of Playboy are a Rorschach Test of sorts, “a culmination of the dreams and fantasies and prejudices you bring to the table.” I came to the company as a child raised in Alabama in the 60s and 70s. In my world, Playboy represented a mysterious, bordering-on-forbidden level of glamour and sophistication, with a just-barely acceptable level of naughtiness. (It wasn’t acceptable to everyone in my family: An aunt and uncle led a prayer group asking God that I not get the job.) My father wasn’t a Playboy subscriber, but it was nearly impossible to not encounter Playboy when I was young. I vaguely recall catching glimpses of the company’s second TV entreaty, “Playboy After Dark,” a black-and-white variety show considered groundbreaking at the time.

And boys aren’t the only ones who remember when they saw their first Playboy magazine: I recall discovering an uncle’s stash (not the uncle who led the prayer meeting) with a cousin and one of my sisters, in a closet in my grandmother’s house when we were tweens.

I began a subscription to Ms. magazine my freshman year and began reading Gloria Steinem (including her 1963 career-launching expose about working undercover as a Playboy bunny in the company’s New York club), and I was fascinated by the company. I left Alabama for college in Chicago, and still remember the first time I drove south on Lake Shore Drive and spotted the 9-foot illuminated “PLAYBOY” masthead that topped the company’s then-headquarters. While an undergraduate, I attended an ACLU-sponsored lecture by Christie Hefner on First Amendment rights, and I became an immediate fan. She was so articulate and poised, and expressed progressive positions and sentiments I was just beginning to understand and embrace.

Fathers and Daughters

Although we now communicate infrequently, I still consider Christie Hefner a friend. As I expressed to her in an email last week offering condolences on her father’s death, she remains among a handful of people in my work life who simultaneously pushed and supported me to become a better professional — and person — during our time together. She and I were never close enough to delve into the complexities and difficulties she must have faced as Hugh Hefner’s daughter, but I sensed she loved him deeply. She told New York Magazine in 1982 that she thought her considerable drive “came from trying to make my father proud of me.”

So it was not lost on me that one of the first times I felt true approval from my own father (who died this past Father's Day at 83) was when I landed the Playboy job, and began working with such a high-profile female executive. My father even asked for a supply of my business cards, and regularly passed them out to friends and acquaintances, referring to me as “Christie Hefner’s left-hand woman.” (I’m a southpaw.)

Christie joined Playboy in 1975, at 24, planning to work a year or so before going to law school. Five years later, Hugh Hefner named her president of the then-struggling company, telling her, “‘I felt like I had this incredible birthday party and you had to come in and clean up the day after,’” she recounted to The New York Times in 2009.

Christie righted the house that Hef built, becoming CEO and chairman in 1988, and returning the company to profitability through some tough business decisions, including closing the more than 40 Playboy clubs. I left the company in 2000, while Christie stayed in the top spot until 2009, becoming the longest serving female chairman and CEO of a U.S. public company, three times being named one of Fortune magazine’s “Most Powerful Women” in business.

Playboy’s Legacy: Empowering or Exploitative?

Amid the airbrushed centerfolds and Hugh Hefner’s much-publicized sexual exploits, Playboy was among the first mass-circulated magazines to publish notable female authors, including Margaret Atwood (who’s enjoying a renaissance with the Hulu series based on her dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale), Joyce Carol Oates and Germaine Greer Hugh. Hefner’s “Playboy Philosophy” espoused personal liberation, and championed social causes, including gay and civil rights. (The Playboy clubs were among the first to feature black performers appearing before white audiences. Many southern states refused to air the company’s early variety show because prominent black performers such as Nat King Cole and Sammy Davis, Jr., mingled among white guests.)

Playboy supported abortion rights on its pages before it was a legal procedure nationally, and even filed a “friend of the court” brief in the landmark Roe v. Wade case that legalized abortion across the country. The magazine also advocated for sex education and birth control.

Founded in 1964, the Hugh M. Hefner Foundation has provided funding for AIDS research and rape crisis centers. It supported the Equal Rights Amendment and gave $100,000 to the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, eliciting a thank you note from a young Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then an attorney for the project and now, of course, a Supreme Court justice.

That’s not to imply that Playboy hasn’t had its share of scandals and controversies. However, in 32 years of professional work across nearly a dozen organizations, Playboy is one of only two workplaces where I never once felt minimized or compromised because of my gender. Granted, I often worked directly with Christie Hefner, and everyone knew it, which probably discouraged untoward comments or behavior. In addition, I primarily worked in the more button-downed Chicago headquarters, far from the company’s free-wheeling West Coast operations. (One of my favorite Playboy-related quips over the years has been, “Yes, I’ve been to the Playboy Mansion — but only during daylight hours.”)

During the time I worked there, women comprised some 20 percent of the company’s senior executive ranks, nearly 40 percent of its managers and more than half of all employees.

Hugh Hefner’s legacy is complicated and to many, problematic. But his company and only daughter opened a world to me that made me a better person, citizen, spouse and mother. On balance, I think that’s true for our society overall.