Frank Mankiewicz: A 7-Decade Career With Purpose

From RFK adviser to NPR chief, he didn't believe in retirement

Talk about encore careers.

In his just-published memoir, So As I Was Saying, the late famed Frank Mankiewicz explained why at an age when many people begin winding down, he was just revving up — taking the plunge into a new 30-year career that lasted past his 90th birthday, an unconventional coda to a remarkable working life:

I was sixty years old when I went into the public relations business — a normal time to have a brief capstone on one's career before retiring. But the mathematics of life in the United States has changed. With America's new longevity, I stayed in the PR business — and the center of DC action — well into the new century.

One Life in 11 Acts

“Dad didn't have a third act. He had an 11th act. His life was a series of acts,” Ben Mankiewicz, Frank's youngest son and host of TCM’s Turner Classic Movies told me. Mankiewicz’s other son is NBC Dateline correspondent Josh Mankiewicz.

There was no blueprint to Mankiewicz’s career, which hopscotched from national political adviser to National Public Radio honcho. He simply stayed engaged. And whatever he did, Mankiewicz loved doing it. “He never intended to retire. He liked being part of the action,” recalled his widow, novelist Patricia O'Brien.

And Mankiewicz stayed in the thick of the action until a few weeks before he died of respiratory failure at age 90 in 2014. "What a marvelous era we live in when the death of a person in his nineties seems premature,” wrote Joel Swerdlow, Mankiewicz's longtime friend and co-author of the memoir. “Frank was among the New Old."

From Peace Corps to NPR to PR

By the end of his life, Frank Mankiewicz had more notches on his belt than many people have in several lifetimes:

- Regional director for the Peace Corps in Latin America

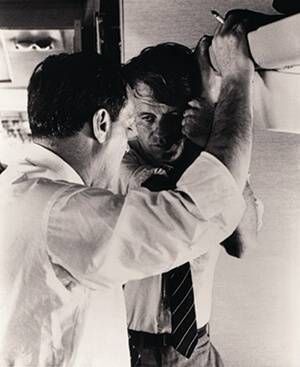

- Robert Kennedy's press secretary during his 1968 presidential campaign (announcing RFK’s death to the world and visiting his grave on each successive birthday)

- Campaign director for George McGovern's presidential quest

- Congressional candidate from Maryland (in 1974)

- President of what is now NPR (then called National Public Radio) where he expanded NPR's listenership and its deficit

- Executive vice president of the public relations and lobbying firm, Gray & Co. and vice chairman of Hill & Knowlton, which acquired it

At NPR, Mankiewicz scored a coup by getting the Senate to allow the radio network the first-ever live broadcast — for the Panama Canal Treaty debates. (Thanks to Mankiewicz, those historic NPR broadcasts first brought me to Washington, D.C. in 1978, where I worked for him and eventually became producer of All Things Considered.)

Given Mankiewicz’s pedigree in Democratic politics and public service, it was something of a surprise in 1983 when, after stepping down from NPR, he was sought out by a prominent Washington Republican.

“Dad phoned me, conflicted, when Bob Gray, who ran a PR agency closely identified with the Reagan White House, offered him a job,” said his son Josh, whose younger brother Ben was a teenager at the time. “Having been in public service, my dad never made any real money, there was no inheritance to prop him up and he never saved a dime. Dad needed to provide for his family. I urged him to take it, he did and it ended up being great."

The Next Job, The Next Challenge

But accepting the public relations position wasn't just about cashing in at the end of a career; he’d been offered and turned down other PR jobs. “It was a lifeline to Dad, an opportunity to utilize a lifetime of being the smartest guy in the room,” said Ben. “For Dad, it was always the next job, the next challenge, the next chapter in a book he had zero interest in finishing.”

Indeed, O'Brien and Swerdlow had long urged Mankiewicz to put his fascinating life between hard covers, but he resisted.

When you grow up in the shadow of Hollywood (the son of Herman Mankiewicz, who wrote the screenplay to Citizen Kane, and nephew of Joseph Mankiewicz, who won an Oscar for All About Eve) and see the likes of F. Scott Fitzgerald and the Marx Brothers at your dinner table, your life story seemingly should begin writing itself.

But Mankiewicz kept procrastinating, almost afraid that by summing up his life he'd be inviting the grim reaper. O'Brien told me: “Frank would say, 'If I write my memoirs, it might be the last thing I do.'”

And sadly, it was.

“Can you imagine how that line came back to me when he died?” O'Brien asked. Mankiewicz died — he detested the euphemism "passed away" — before writing the book’s acknowledgments.

His Views on Retirement and Death

Mankiewicz's theory of retirement, said Ben, is best summed up by his dad’s quotation of one of his many boldface clients, former Defense Secretary Clark Clifford, who worked into his 80s: “I can keep doing new things or retire and sit on the porch and wait to die.”

Frank Mankiewicz never thought he would die. At least, he promised as much to his son Josh after his pet turtle died when he was four.

“Am I going to die?” Josh asked his dad.

“Yes, some day,” he remembers his dad saying.

“Is Mom going to die?”

“Eventually, a long time from now.”

And then he asked his Dad. “Are you going to die?”

“No, no, I'm not.”

That comforted Josh. “And I thought, no matter what happens, Dad will be around.”

It was this eternal optimism that O'Brien believes was the secret to Mankiewicz's 30-year encore career. “He never had the brake on. I think a lot of people as they grow older, start putting the brake on. He wasn't clinging to work. Work was an extension of who he was.”

Concessions to His Age

By his mid-80's, Mankiewicz made a few concessions to age, giving up the car and taking the bus to work in Washington, D.C. But when The New Yorker wrote a piece in 2012 about Walter Cronkite urging Robert Kennedy to run against Lyndon Johnson and questioned Mankiewicz's assertion that he was at that meeting, “Mankiewicz went into a depression for days,” said Swerdlow. “Why does it bother you so much?” Swerdlow asked. “You try being 88 and have someone tell you that you can't remember something,” he shot back.

Mankiewicz concluded his memoir saying that “I have reached my ninetieth birthday in good health and actuarial tables say this means the chance of reaching a hundred in good health is hardly remote.” But his heart had other ideas. He worked on a Friday, was admitted to the hospital the next day and was gone weeks later.

Two days before his dad died, Josh was reading the paper to him in the hospital room, sharing the news that former Washington Post legendary editor Ben Bradlee died. “He said, 'Ben Bradlee. Good guy. Says f*@k a lot,'” said Josh. “A pretty good six-word obit.”

A Fondness for Words

Perhaps more than anything else, Mankiewicz loved words. Watching an NFL game in the early 1980s, he heard an announcer use the term “natural turf.” Wow, he thought, that's what we called “grass.” So Mankiewicz invented the word “retronym,” now in the dictionary, to describe a word or phrase used when societal (or scientific) change makes the original word too imprecise — such as “cloth diaper” or “acoustic guitar.”

When I worked for Mankiewicz, he invented another word: “klong,” defined as “a sudden rush of ___ to the heart.” It’s the feeling you get when you suddenly remember you have dinner guests coming over and you're across town or even worse for me, the feeling you get when you receive word that Frank Mankiewicz died — didn't pass away — but died, after an extraordinary life.