A Call for a Humanitarian Response to Alzheimer's

'The Problem of Alzheimer's' author Dr. Jason Karlawish says it’s time to help caregivers and patients reclaim their lives

"Once upon a time," writes Dr. Jason Karlawish, "Alzheimer's disease was a wild beast. It crept up, took hold of a person and then their family, and it never let them go. It was tireless. Efforts to tame it were futile. But now it is changing. It's becoming domesticated."

The author of the engrossing new book "The Problem of Alzheimer's" says everything changed 20 years ago when for the first time "we could definitively see the disease — and only part of the disease — in a living human, using the biomarker that measures amyloid in the brain." Before that, families of the 6 million Americans with Alzheimer's could only be sure the disease had taken hold of their loved ones after they had died and were autopsied.

"We should expect that Alzheimer's disease will be a disease that's treatable and we can learn to live with it."

Think of research into Alzheimer's as a giant jigsaw puzzle. So, when Eli Lilly announced this month that its experimental drug donanemab slowed cognitive decline in early-stage Alzheimer's patients by six months, it may have found a puzzle piece.

The Alzheimer's Association called the result "encouraging and promising." And Karlawish tweeted out: "This is the beginning of the biomarker-drug redefinition of Alzheimer's disease." [Biomarkers can help target treatments, measure drug response and reduce the risk of adverse drug effects.]

But given the disappointment with many Alzheimer's drugs previously, it will be necessary to validate the data in additional trials that follow more patients over a longer time to determine donanemab's efficacy and safety to preserve a patient's memory.

If the data continue to hold up, Karlawish says, this would be "a big event in the history of the disease."

A physician, writer and med school professor at the University of Pennsylvania,, Karlawish is also co-director of the Penn Memory Center in Philadelphia. That center offers diagnosis and treatment for those 65 and older with mild cognitive impairment or dementia caused by Alzheimer's disease and other age-related progressive memory disorders.

For Karlawish, it's not just advances in Alzheimer's drugs that are the measure of progress. Alzheimer's, he insists, should be viewed as a humanitarian problem where patients and caregivers can improve the quality of their lives — hence, the subtitle of his book: How Science, Culture, and Politics Turned a Rare Disease into a Crisis and What We Can Do About It.

"We knew he had dementia, but ... no one ever sat us down to give us any help for how to manage things."

Next Avenue spoke to Karlawish about his book and why he pursued a career focused on Alzheimer's care and research:

Next Avenue: You had every intention of becoming a critical care doctor but describe in the book how you switched your fellowship to geriatrics in large part because of the way your ninety-year-old grandfather was treated by the health care system.

Dr. Jason Karlawish: He got the best of care, but the worst of care.

Once he had a clearly reimbursable operative problem — a hip fracture — the health care system stepped up with the best of technologies and interventions, but it was never able to care for him.

He developed a devastating delirium and was a victim of the chaos of the long-term care system — the transfers from hospital, nursing home and back. And slowly but inevitably, the American health care system killed him.

We knew he had dementia, but we didn't really get a clear diagnosis. And no one ever sat us down to give us any help for how to manage things. This was back in the nineties. And the sad thing is, is that story is still too common for outpatient diagnostics and inpatient care.

Looking back on your switch to geriatrics, was this a way to honor your grandfather?

He died within a matter of months of that switch. There's no question the grief I felt about what happened to him worked on me.

I'll tell you candidly, two decades later, sometimes in settings where I talk about the experience, I catch myself about ready to sob. I think probably if I start talking about it more, I might do the same thing now.

You talk in the book about how Alzheimer's caregivers are unique, not just in their tasks and the time needed to do them right, but you say in some respects, 'they are controlling the truth,' that they literally become an extension of the Alzheimer's patient. That's an awesome responsibility. Who trains family caregivers to fulfill that role?

You picked up on one of the key insights I made as I wrote this book: Caregiving isn't just tasks. It is this seemingly ordinary, but very morally intense, work of extending the mind of the person with dementia.

And it ups the ante for taking caregiving seriously as a nation and [compels us to] ask ourselves, currently, 'How do we support them? How do we train them?' The average person just sort of stumbles into the caregiving role and is left to figure it out on his or her own.

And, you know, I chronicle how in our memory center, families literally breathe a sigh of relief when they sit down and meet with our social work team and finally get an answer about how to handle the current problems, how to plan for the future, how to effectively communicate with their relatives. So those are all doable things. We just invest in providing those core resources, just like we provide nutrition counseling to people with diabetes.

The Alzheimer's Association says we had forty-two thousand more deaths from Alzheimer's last year during the pandemic. Why does Alzheimer's make you more vulnerable to COVID-19?

Imagine you're a resident of a long-term care facility. You've got a good set of folks who come and care for you every day and periodically, family caregivers come in. Imagine, all of a sudden, half the staff is gone because they're ill with COVID and those family caregivers are locked out. Four or five, six, eight weeks later, you're not eating. You've not gotten out of bed. You've developed, therefore, a weakness. You've developed confusion, and you're just more susceptible to accelerating the pace of your disease.

COVID was proof positive that we need humans to care for humans. It was an awful natural experiment: What happens if you take away humans caring for other humans? From that, I hope that we learn the need to support caregivers better than we had before COVID.

The Food and Drug Administration has not approved an Alzheimer's drug since 2004. When effective Alzheimer's drugs are finally approved, you're concerned that the country won't be ready for them. Why?

We're not ready. What has to happen is the rapid creation of diagnostic and therapeutic centers that can rationally diagnose and prescribe persons who should be getting treatment and care. There are just not enough clinicians to do that. And that's going to require a national network of centers. We're going to need aggressive use of telemedicine and other remote techniques to deliver the services.

Toward the end of the book, there's a somewhat hopeful note when you say that 'biomarkers will redefine when we have Alzheimer's and when we are dying of it.'

I agree 'somewhat hopeful' because I think that we have a lot of work to do about how we're going to treat and respect the minds of persons who are disabled. And I don't think we've arrived at that point. I think we have a lot more work to do as a culture. And I do close the book with a pretty blunt criticism.

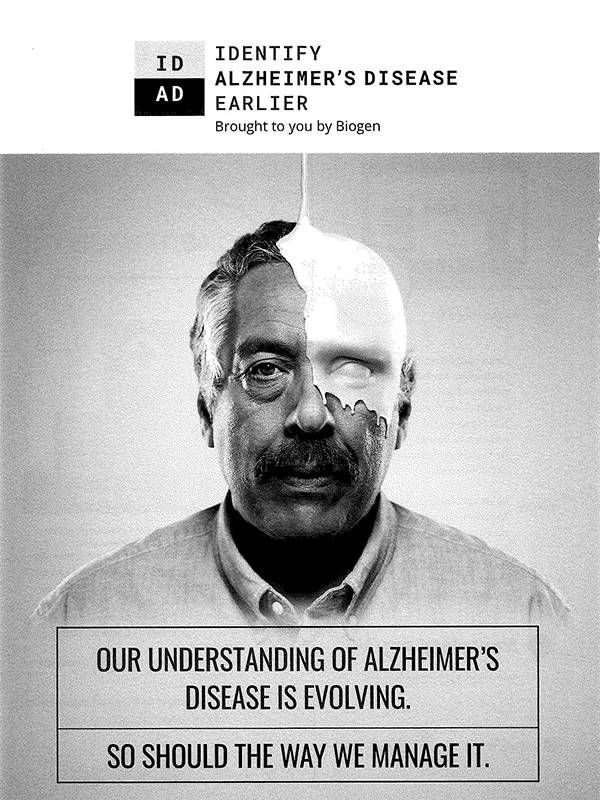

For example, the ad by Biogen that depicts a person with an amyloid image that looks like the living dead, "The Phantom of the Opera," in which half the person's face looks like a skull and the other half looks alive. That's not the kind of imagery that's going to help us respect the person, recognize the mind of the person living with Alzheimer's disease.

Reading the section of your book about stigma and language, I flashed back to a spring break trip to Florida during college when I visited my grandmother who had dementia. I was horrified to see her wandering around her place in a nightgown, not completely sure who I was and remember being ashamed that I told my family that my grandmother looked like a zombie, one of the words you urge people to drop when describing those with dementia.

There are aspects of the zombie trope that do describe living with dementia — wandering, being unkempt, potentially having trouble speaking. You get why the zombie trope is attached to them. But that doesn't mean that we should embrace the fullness of the zombie trope because inherent in it is [the idea] that the person is dead before they're dead.

What's the one takeaway you hope readers of the book grasp?

We should expect that Alzheimer's disease will be a disease that's treatable and we can learn to live with it. That relies on progress in science and in our culture. We need to see this disease as a humanitarian problem.