U.S. Workers Need a Workforce Safety Net

A report from The Aspen Institute 2016 Economic Security Summit

Low-income Americans have the semblance of a safety net stitched together by federal government programs — albeit a frayed one. But after attending The Aspen Institute 2016 Economic Security Summit: Reconnecting Work & Wealth in Aspen, Colo., in October, I’ve concluded that it’s now time for a safety net for the American workforce.

Such a safety net, created by the government and employers, could have three significant effects. It could: 1) help more workers get into, and stay in, the middle class, particularly minorities; 2) better tailor a system of benefits to the 21 century workforce, particularly the growing numbers of independent workers in today’s Gig Economy and 3) reduce Americans’ painful financial insecurity and instability.

“Everybody once had a shot at the middle class. Then something terrible happened. The social contract frayed,” said Heather McGhee, president of the Demos think tank, at the Economic Security Summit, a gathering from The Aspen Institute think tank of roughly 40 experts on work and financial security.

The Precarious Americans

As Holly J. Lawrence recently wrote on Next Avenue, a CFED study just noted that nearly half of households lack a basic personal safety net to prepare for emergencies and that America’s racial wealth divide is staggering and getting worse.

“It’s not clear African Americans ever had a fixed path to the middle class. People say now is the time. It’s been the time,” Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, director of CFED’s Racial Wealth Divide Project, said at the Aspen Institute Summit.

Layer on to all of this the troubling findings from the Pew Research Center’s report, The State of American Jobs: The share of workers with an employer-sponsored health insurance plan fell from 77 percent in 1980 to 69 percent in 2013 and the share of workers with access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan peaked at 57 percent in 2001 and dropped to 45 percent in 2015.

The two-day Summit covered a wide variety of topics, from “The Breakdown of Pathways to the Middle Class” to “Restoring Work as the Foundation for Economic Well-Being." I’ll focus on two needs I heard about: The need for employer-based emergency savings and the need for pro-rated, portable, universal benefits.

As Maureen Conway, executive director of the Economic Opportunities Program of The Aspen Institute has written, “Our laws were made for the industrial age.” They need to be modernized, Conway says, to support “both strong business and strong values about work.”

The Need for Employer-Based Emergency Savings

You’ve seen the startling statistic, perhaps on Next Avenue: 47 percent of Americans would have trouble coming up with money for a $400 emergency, according to the Federal Reserve. (This was the theme of the buzzy Atlantic article by movie critic/journalist Neal Gabler, The Secret Shame of Middle–Class Americans.)

Aspen Institute Summit participant Rachel Schneider, senior vice president at the Center for Financial Services Innovation (CFSI), knows all about this. She’s a principal investigator for CFSI’s groundbreaking U.S. Financial Diaries research study, which collects information about the spending and savings patterns of more than 200 households.

“We used to think of the financial model built around a lifecycle arc: When you were young, you got an education and then a job and your income would grow over time and you would build wealth and spend it down in retirement. With our experience with families, we don’t see evidence of that arc,” said Schneider. “We see rocky roads with people dealing with near-term financial challenges all the time."

Those challenges partly explain why roughly one in four workers with employer-sponsored 401(k) retirement plans tap those accounts for reasons other than retirement.

Breaking Into 401(k)s

“It’s a tragedy for long-term wealth building that when some people are faced with financial hardship, they take out 401(k) loans and stop making contributions,” said Anne Lester, head of retirement solutions for Global Investment Management Solutions, J.P. Morgan Asset Management, at the Summit. ‘They can’t pay back their loan, which they have to do, without stopping their contributions, which creates a huge pothole for future wealth building.”

Employees often go that route because the easiest way for them to save is through 401(k)s, with automatic payroll deductions and, often, employer matches.

Wouldn’t it be great if employees could save for short-term emergencies through their employers this way, too — without fear of IRS tax penalties? I think so.

Some of The Aspen Institute participants thought so, too. But, they said, there are too many regulatory roadblocks. One long-term member of the asset-building field observed there that “a test of the Auto IRA for emergency savings ran afoul of state labor laws and we haven’t figured out a way around it yet.”

Back in 2013, I wrote a Next Avenue blog post noting that the financial wellness advisory firm for employers HelloWallet (now a division of Morningstar) was urging firms to offer emergency-savings plans to employees. I just checked back to see how it’s been going.

“It turned out to be not super-viable from our perspective,” said Rob Pinkerton, Morningstar’s chief marketing officer. None of The Aspen Institute participants mentioned any major employers with short-term savings programs.

U.S. Labor Secretary Thomas Perez spoke at the Summit, too, and since I knew the Obama Administration has made assisting retirement savers a priority (the myRA and the fiduciary standard), I asked him what it was doing to help Americans increase emergency savings. Rather than reducing regulations to permit employer-based plans or creating a savings incentive, he said, “Our strategy is to lift wages” and that the government is “working to address pressure points that lead people to a financial crisis,” such as making it easier to get health insurance through the Affordable Care Act.

“When the pillars are better fortified, you’re in a better position when you have a $400 unexpected payment,” said Perez.

The Need for Portable, Prorated, Universal Benefits

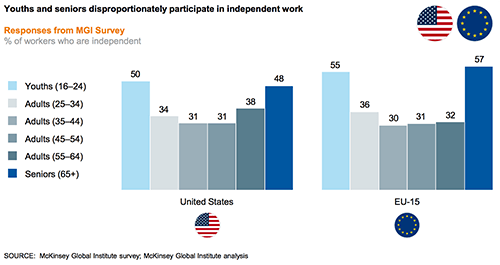

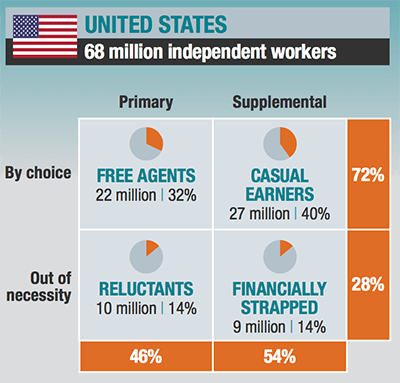

It’s the growing number of Gig Economy independent workers —54 million to 68 million by McKinsey & Co.’s new estimate — who arguably need financial protection the most these days.

Uber drivers, Etsy sellers and the like have income that’s often extremely volatile and no employer providing health insurance, disability insurance or a retirement plan. Increasingly, boomers and Gen X’ers will join the Gig Economy ranks to pick up part-time income in retirement after leaving their full-time jobs.

“It is urgent to consider how to provide low-income independent workers — and, for that matter, workers in precarious traditional jobs — with a greater safety net and pathways to improve their skills,” wrote the authors of the new, important McKinsey Global Institute report, Independent Work: Choice, Necessity and the Gig Economy.

One novel idea I heard at the Summit: Let’s convert the employer-based system of benefits, whose usefulness depends on where you work and how much you work, to a pro-rated, portable, universal system. President Barack Obama and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) have called for portable benefits.

Natalie Foster, an adviser to The Aspen Institute’s Future of Work Initiative, believes portable benefits would help stabilize the otherwise precarious nature of 21-century work. “We need this Uber moment to prototype what this safety net would look like,” said Foster at the Summit. “There needs to be a federal response.”

In their notable 2015 Democracy Journal article, “Shared Security, Shared Growth,” Nick Hanauer and David Rolf devised what they called a “twenty-first-century social contract.”

Under their Shared Security System scenario, every U.S. worker would have a Shared Security Account with “basic employment benefits necessary for a thriving middle class.” You’d be able to take your benefits from one employer to another. You’d also receive a pro-rated portion of them based on the number of hours you worked; that way, part-timers and independent workers would receive health insurance and could contribute to retirement plans.

“We need to think beyond the words ‘employer’ and ‘employee,'” said Summit participant Althea Erickson, global policy director at Etsy, the online marketplace for buying and selling handcraft goods. All workers, Erickson said, need “a single place to manage benefits regardless of where they are earning income. A federal benefit portal similar to the federal exchange in the Affordable Care Act, but for all benefits.”

A year ago, 40 labor leaders, political people and marketplace CEOs from places like Lyft and Etsy got together to design principles for a portable safety net. “For the first time, labor and companies said: ‘We have to create something for the future,’” said Foster.

You can read the first pass of it in Portable Benefits in the 21 Century, a report from The Aspen Institute’s Future of Work Initiative. And kudos to Etsy, which just came out with its own thinking in Economic Security for the Gig Economy: A Social Safety Net That Works for Everyone Who Works.

Both are worth reading, I think. Clearly, there's a ways to go to make this idea a reality. But I hope that policymakers, employers, benefits firms, Gig Economy companies and the next President of the United States read the reports and get to work before what passes as a safety net frays even further.