A Chat With 2 Creative Superstars in Their 70s

Novelist Judith Freeman and her husband, photographer Anthony Hernandez, on their work, their lives and their loves

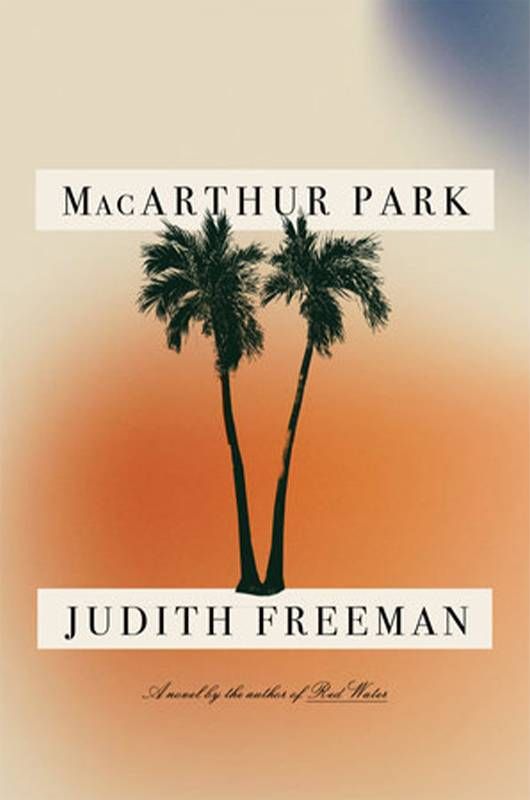

The narrator of Judith Freeman's new novel, "MacArthur Park," has a lot in common with Freeman, 75. She is a prominent writer (author of eight books), a longtime resident of Los Angeles and for many decades, the wife of an accomplished creative professional. Freeman herself is married to internationally known photographer Anthony Hernandez, 74, famous for work that ranges from street photography to abstract compositions.

In "MacArthur Park," after her 20-year marriage falls apart, Verna, the book's narrator, flees her small town in Utah and heads to L.A. There, in her late 30s, she reconnects with a childhood friend, Jolene, now an important feminist artist. The novel looks back at 30 years of Verna's life, including her second marriage to a man once married to Jolene as well as Jolene's terminal illness and end-of-life plans.

I asked Freeman and Hernandez to talk about "MacArthur Park" and to chart their lives together, from their first meeting to their decades as successful, sometimes provocative artists.

"I felt nervous using so much of my own experience to write this novel."

M.G. Lord: How would you describe 'MacArthur Park?'

Judith Freeman: I suppose 'MacArthur Park is a 'bittersweet novel,' like life itself. But especially life as viewed from the perspective of maturity.

When we reach a certain age and look back at our pasts and all that has happened, we often feel nostalgic for the things we miss or wish hadn't changed so much. For instance, I miss writing and receiving letters, as does my character Jolene, who feels an entire history of an era is being lost, for who saves emails?

Like you, the narrator of 'MacArthur Park' wrote a nonfiction book about Raymond Chandler. You named her Verna, after the narrator of your first novel, 'The Chinchilla Farm.' Even her cats share names with your cats.

Judith Freeman: I felt nervous using so much of my own experience to write this novel. For instance, Verna and her husband are evicted from an apartment where they have lived for many years, tricked by an evil new landlord who lies and cheats to get them out. Tony and I also lost our much-loved apartment in MacArthur Park in L.A. under similar circumstances.

"I taught myself to write the way writers have done for eons, by studying the work of writers I admired."

It's extremely painful to lose a home where you've lived for over forty years — even if that home is a rented apartment. But even more convulsive when one is forced out through dishonesty and intimidation.

I wanted to write about that experience, in part because so many people are struggling with housing today: it's a great crisis. But that often means delving into very personal issues where I know I'll feel exposed. And I also might expose people who I'm very close to, in this case my husband.

But I remember what [author] Joan Didion once said in an interview when she was asked how her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, might feel about her writing about their marriage, even when fictionalized and whether that had been a problem. She said as writers they both understood they had a right to use their own lives in their work. I think Tony understands this as well, because he is an artist.

Anthony Hernandez: Living with another artist means sharing everything. And the work, whatever it might be, is the life lived. And that's the art that must be respected.

How did you and Anthony meet?

Judith Freeman: Tony and I met a museum opening in L.A. in 1985. We were both thirty-nine. I had not yet published a book and Tony didn't have a gallery yet. When we met, we decided that we wouldn't take jobs, but try and live off our art. And somehow, we were able to do that, with the help of cheap rent.

Had you planned careers in the arts?

Judith Freeman: Books didn't figure into my childhood. I was much more interested in the outdoors and animals — the horses and dogs I loved and exploring the mountains and woods where we lived in Utah.

I got married at seventeen, and had a child at eighteen, a son [Todd] who was born with a serious congenital heart condition and who endured two heart surgeries before he was three.

The second operation took place in Minnesota, and I ended up on the campus of Macalester College where I could take a few classes. I enrolled in a literature course and discovered great writers — Hardy, Lawrence, Cather, and James — and at that moment, at the age of nineteen, I decided I wanted to be a writer.

I taught myself to write the way writers have done for eons, by studying the work of writers I admired.

Anthony Hernandez: I was born and raised in East L.A. My parents were from Mexico. Growing up, I had no idea about art.

After high school, I took a couple classes in photography at East L.A. Junior College. I thought I might become a fashion photographer. But I discovered the work of Edward Weston and that changed my idea of photography.

I knew I wanted to be an artist. I dropped out and started taking pictures.

The draft interrupted those plans.

Anthony Hernandez: I spent fourteen months in Vietnam as a medic. When I got back, I started taking pictures again — black and white street photographs in downtown L.A.

You also made an unforgettable color portfolio of Beverly Hills in the '80s. Yet Judith's work gained popular acclaim before yours did. Was that ever an issue for you as a couple?

Anthony Hernandez: Everything we have is through our work. Judith getting a Guggenheim Fellowship early on, in 1996, was great. And my getting one late, in 2019, was okay because it's better late than never.

But it also coincided with many good things happening for me — my retrospective at SFMOMA in 2016 and being included in the Venice Biennale in 2019.

In 'MacArthur Park,' Verna's childhood friend accepts life's last chapter — death — with both defiance and acceptance. Was this difficult to explore?

Judith Freeman: 'MacArthur Park' was a hard-earned book. In the middle of writing it, my son, Todd, died. He was fifty-three, a schoolteacher and simply a wonderful person — my only child. He suffered a sudden heart attack and was put on life support for five days before it became clear we had to let him go.

This happened at the beginning of winter. We had just lost our apartment and moved everything up to our little farm in Idaho. He died in Boise, and afterward we came back to the prairie and spent a very long, cold, difficult winter here, isolated from our friends and family in L.A.

I felt such deep grief I couldn't write, couldn't go back to work on 'MacArthur Park' or even read or do much of anything at all. The sadness seemed paralyzing.

And then after a few months, days that felt so baggy and formless and sad, I realized I needed to go back to work, and I began writing again.

I feel the novel saved me. It brought me back into the world by allowing me to disappear each day into the world I was creating.

I think I always knew that Todd might pass before me, we knew he had a fragile heart — he had survived longer than any other adult who'd had the early experimental surgery as a child — and yet he lived such a full life, without fear, always giving so much to his students and family.

I finished this book for him, with the example of his lifelong courage always before me.