Inside the Smithsonian's New African American Museum

This national treasure has special significance to people who lived through the '60s

Late last week, just eight days ahead of its official opening, the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture, was still surrounded by a chain link fence. Workmen were in a mad dash, putting the finishing touches on the $540 million, 400,000 square-foot African-American museum — the 19th bearing the Smithsonian brand.

Inside, drawings, photographs, spoken word and video tell the African-American story, delving into a breathtaking 600-year history that is both jarring and inspiring.

1 of 6

Ten shards of stained glass from the 16th Street Baptist Church (1963)

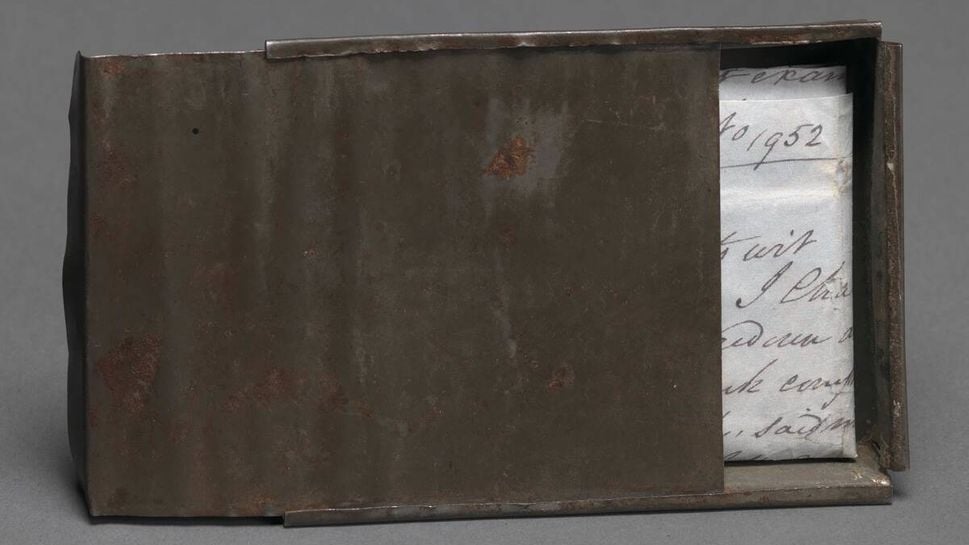

Freedom papers and handmade tin carrying box belonging to Joseph Trammell (1852)

Cabin from Point of Pines Plantation in Charleston County, South Carolina (1800-1850)

Felt hat with medallion worn by Bo Diddley (1992)

Cradle made by an enslaved person

Couch from the set of The Oprah Winfrey Show in Harpo Studios (2002; reupholstered 2015)

Outside, John Franklin — a Smithsonian veteran who's worked on this project for 11 years — greeted me with historic maps that told the story of the ground we were standing on: five acres that were once occupied by a Maryland plantation, complete with slaves. The White House is just a few blocks away.

A hundred years in the making and smack in the middle of the National Mall, this stunning structure boasts one of the most prominent addresses in the U.S. capitol: 1400 Constitution Avenue NW. Enveloped by cascading tiers of bronze-tinted metal latticework, the museum is just yards from the Washington Monument, centered between the Lincoln Memorial (site of the 1963 March on Washington and Martin Luther King's "I have a dream" speech) and the U.S. Capitol (where the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act were hammered out 50-odd years ago).

"I like to say we're not between 14th and 15th streets, but between the 14th and 15th Amendments," Franklin says, referring, respectively, to The Equal Protection Clause and the prohibition against using race to exclude people from voting.

To underscore the museum’s proximity to power, Franklin mentions that the Obama family had an even earlier peek inside the museum. As if on cue, the president's motorcade, sirens blaring, whizzes by.

Not So Long Ago

The hope of Franklin’s father, the late John Hope Franklin, a celebrated historian who chaired the museum's scholar advisory council, was that the museum would tell the "unvarnished truth" about the African American experience. He needn't have worried.

Inside, you’ll find a slave cabin from a South Carolina plantation, a segregated rail car, the guard tower from Louisiana's notorious Angola Prison and the casket that carried the body of 14-year-old Emmett Till, lynched in 1955 for whistling at a white woman — to name a few of the 3,000 objects on display in the inaugural exhibits.

Like many born in the early to mid-1950s, Franklin and I share a timeline, a coming of age during the height of the Civil Rights protests, a period that also saw the assassination of a president, a civil rights leader and a presidential candidate. But our experience differs.

Franklin is black, and I'm white. And until he shared his own “unvarnished truth,” I wasn't fully prepared for just how intertwined his life would be with many of the exhibits we were about to see. As we toured the museum, he related personal experiences:

- "When my father was a professor of history at Howard University in the 1950s, we would leave Washington to visit my grandparents in North Carolina and my parents would call ahead to friends in Petersburg, Va., and Raleigh, N.C., so we could use their bathroom. Gas stations wouldn't let us use their bathrooms, but we could buy their gas."

- "When my father became chairman of the history department at Brooklyn College, the first African American to chair a department in a historically white university, it was front-page news in The New York Times, but no bank in New York would loan us money for the house we wanted to buy."

- "My mother wasn't permitted to try on clothes in the Washington department stores."

- "The National and Warner Theaters down the street... We couldn't attend those theaters."

- "My parents and grandparents couldn't swim because there were no pools at the black schools they attended."

Each of Franklin's stories — and there were many others — is part of this museum's raison d'être. "It's very difficult for young African Americans today to realize that not so long ago we couldn't go anywhere we pleased in the nation's capital," he says.

Uplifting and Emotional Exhibits in the African American Museum

In addition to acknowledging such grim facts, the museum also celebrates African American achievements in the arts, sports, music, literature and politics.

After watching an orienting film by Oscar-nominated cirector Ava DuVernay (Selma) in a theater off the lobby, Franklin tells me, "museum visitors will take an elevator from the present and travel underground to 1400 A.D. when slavery existed in Africa, even before the first crossing to this territory.”

They will then work their way up the building — in a kind of uplifting movement — through segregation, the civil rights struggle and eventually, the election of the first African American president and beyond. Barack Obama will participate in the opening ceremonies, Saturday Sept. 24, a fitting gesture at the end of his second and final term.

No matter how many times Franklin has been through the still unfinished exhibits, he says, it’s an emotional experience. We see the original black and white dolls from the famous Kenneth Clark 1940s experiment, in which Clark asked children: Which is the nice doll? Which is the pretty doll? (African American children didn't pick the black doll, which led Clark to conclude that discrimination hurt their self-esteem.)

In the the 1960s section, we see one of the original Woolworth lunch counter stools from the Greensboro sit-ins. Next to it, there's a long interactive lunch counter where visitors can call up information about the Freedom Rides or Colored Waiting Rooms and other important pieces of history of that period.

At the photograph of civil rights leader Medgar Evers, Franklin stops to share a story:

"Just a few years ago, I met Myrlie Evers, Medgar Evers' widow, at the same home (now a museum) where in 1963 she's sitting on the bed with her children, waiting for her husband to arrive. The children recognize his car, say 'Daddy's home!' and then they hear the gunshot. They go to the ground because they know they're under fire. Myrlie tells me the children say, ‘Daddy, get up! Get Up!’ But he's dead. Every day, she tried to scrub the blood off the driveway, but it wouldn't go away. The bullet went through the kitchen window and hit the door of the refrigerator, that is still on display. More than 50 years later, she's telling me 'I'm surprised I'm getting emotional about this.’ And I say, 'You witnessed the assassination of your husband and you're recounting this in the location where it occurred. Of course you're going to be emotional.'"

A Personal Connection

As we walk past the museum's Contemplative Court, which will feature a ring of water showering down to a pool, Franklin points out the honor bestowed on his father. An inscription on the wall reads, “In Honor of John Hope Franklin.” “That's my dad’s name. That’s my dad," he says, proudly pointing it out to construction workers.

A video of John Hope Franklin greets us when we duck into the room housing the exhibit recounting the Tulsa race riots (Franklin prefers the term “massacre”) of 1921, where 300 died. Franklin's grandfather lived through the riots. And his dad testified on the devastating impact of the riots on the city. That event, he wrote, “turned Tulsa's African American district into a scorched wasteland of vacant lots, crumbling storefronts, burned churches and blackened, leafless trees."

We poke our heads into the 350-seat Oprah Winfrey Theater, named for the museum's biggest donor ($21 million). Winfrey was born into poverty to a teenage mother in rural Mississippi. At the museum, visitors can see the iconic couch from her long-running afternoon talk show. It’s a fun piece of pop culture. But Winfrey is serious about the important role the museum will play in helping future generations understand African-American history.

"My generation failed — capital F — for not passing on to the children a sense of knowing from whence we've come,” she told Washington Post Magazine recently. “They only pay lip service to it, and it's not honored and valued and treasured."

Winfrey had an aha moment when young people — both black and white — saw the film Selma and asked "Did that really happen?” She said: "The museum will stand as a living, ongoing, evolving testimony that yes, that did happen and how important it was that we acknowledge the fact."

As we head for the exit, Franklin channels his father and echoes that statement: "The African American story is an extremely complex story, and it's a story we have been taught in a rather simplistic manner, that has nuances — a range of achievements and defeats,” he says. “You have to let people know some of each."

(All Smithsonian museums are free, but demand for tickets to the National Museum of African American History and Culture is so great that timed passes are distributed online. September and October tickets vanished quickly. Currently, only weekday passes are available for November and December.)