A Visit with Officer Clemmons from 'Mister Rogers' Neighborhood'

Singer François Clemmons says he learned about unconditional love and trust from his friend, Fred Rogers

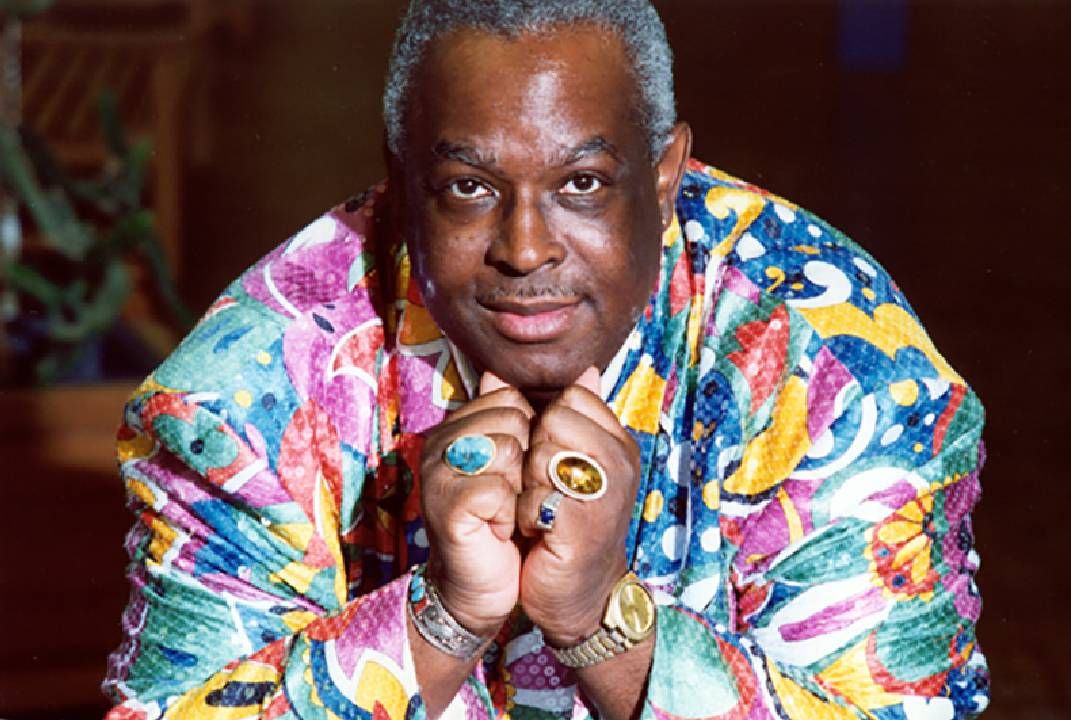

You may remember the character of Officer Clemmons, the police officer/singer who was a friend of Fred Rogers on the beloved PBS TV show, "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood," from 1968 to 1993. But Dr. François S. Clemmons and Rogers were close friends off the stage of the children's program. In fact, Clemmons grew to view Rogers as a father figure throughout his adult life.

Clemmons, 77, earned a Bachelor of Music degree at Oberlin College and continued to Carnegie Mellon University, completing a Master of Fine Arts. He won a Grammy for his recording of "Porgy and Bess" in 1973, and in 1986, Clemmons founded the Harlem Spiritual Ensemble.

Clemmons always had a love of singing, and his grandfather shared ancestral stories with him using his cane as a narrating voice.

He left "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" in 1993, going on to direct the Martin Luther King Spiritual Choir at Middlebury College in Vermont, and holding the Alexander Twilight Artist in Residence until 2013. He received an honorary doctorate from Middlebury College in 1996, and Vermont's Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts in 2019.

In his memoir, "Officer Clemmons," Clemmons writes not only of his relationship with Rogers and his time during the airing of the show, but he also offers a raw, courageous look at what it was like for him to live as a gay Black man during the '60s and '70s.

Songs of Childhood

Clemmons always had a love of singing, and his grandfather shared ancestral stories with him using his cane as a narrating voice.

"Granddaddy Saul was the caretaker for me, and he would be the voice of the cane. As a young child, I just thought that was the most wonderful, magical thing that could happen to a person. The cane would sing to me and my granddaddy, and those few times when I mentioned it inadvertently, the rest of the family would poo-poo it and say 'you know that's not true. That cane doesn't sing,'" says Clemmons. "I would hear them fussing and I'd say, that's our secret. Nobody else knows the cane can sing but me and Granddaddy. That was one of my absolute pleasures."

After Clemmons' parents separated, he moved with his family from Alabama to Youngstown, Ohio, in an area called "The Bottom." Clemmons, traumatized by the death of his grandfather and the violent end to his parents' relationship, grew to call the area home.

"When I was in pre-K, the schoolteacher sat with me and sang songs, and she pretty much ignored my silence. I saw the other kids with her, and they were having so much fun that I felt I wanted to be a part of it and that's when my singing became public," says Clemmons. He quickly learned which areas of the town were safe for a young Black boy, and which churches welcomed him and encouraged his love for music.

A Connection Through Music

Clemmons earned a spot in the choir at Third Presbyterian Church. Fred Rogers' wife, Joanne, was also a member of the choir, and they struck up a friendship.

"Joanne was so much fun. There was something about being around her that was very positive. I sat near her in the choir, and she'd say you've got to meet my husband," he recalls. "I would say, 'I don't need to meet your husband. I like you. I'm glad to be here with you.'"

But it was meant to happen. The choir participated in a concert of spirituals at Third Presbyterian Church. Clemmons says, "Everybody came up to say, we're very glad that you're now a part of our church and our choir. The last person in line I almost ignored — he was so self-effacing. He was so quiet. I thought, he is probably too shy to say anything. I was ready to leave, and Joanne said, 'You can't leave yet. You must meet Fred.' I was still in the sanctuary when he greeted me. The look in those eyes had a gift, and he had a purpose."

A Helper in the Neighborhood

The two men connected. "Now that I'm 77 years old, I understand the effects of looking upon someone and the blessing, the anointment, that he gave me on the spot," says Clemmons. "He saw something. And so, he invited me out to lunch, and I made a big joke about not wanting to go to have lunch with an old man unless he was paying for it. And I went to lunch with him and as the saying goes, I never shut up and he never stopped listening. I learned a lot about listening from him, and the importance of being able to listen."

Rogers asked Clemmons to play a part in his children's program, which eventually became a regular role as a police officer.

"He said to me, you will become a helper, and maybe you can help us change that image of the policemen that you have."

"I was so shocked. How could he ask me to be a policeman when I grew up in a neighborhood where policemen were not very nice. I had seen things," says Clemmons. "But he said to me, you will become a helper, and maybe you can help us change that image of the policemen that you have. Because when people get lost, they'll turn to you. In the neighborhood, if somebody wants a special fountain, a special song on occasion, you'll come, and you will bless them with your singing."

He continues, "The thing that convinced me is three-pronged. He said I would be a helper. It was going to be a job and I could make a living. And I was beginning to feel a kinship to this strange man who was so kind and so patient and so caring to me."

In the Pool with Mister Rogers

On his show, Mister Rogers often addressed problems that children may face in their lives. He brought up difficult, sometimes traumatic issues, such as death and racism. As an ordained minister, Rogers had honest, gentle conversations about these topics.

One memorable episode involved Clemmons, and a still of that episode is the photo on the cover of Clemmons' memoir. The episode aired in 1969 during a time when pool segregation policies accompanied civil unrest.

"I was very upset that they were putting chemicals in swimming pools in urban centers to keep Black children from swimming," says Clemmons. "There were a significant number of white people didn't want them around and felt that they were a negative presence, and all I could think about is it's like a wound. How do you do that to a child? I went to Fred, and I was absolutely incensed. Inconsolable."

A few weeks later, Rogers approached Clemmons with a script. At first, Clemmons felt the script was not strong enough in its message, and he discussed his feelings with Rogers.

"He said in doing that episode, he felt more forgiveness for those that would do such a cruel thing than he felt anger or wanting to punish them. Well, I was not ready for that kind of altruism, that love," Clemmons recalls. "I'm writing my second book and I talk about unconditional love, which he taught me. Unconditional trust, which we learned together. That I could trust him."

A second pool scene with Clemmons was aired in 1993 on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." Clemmons sat down with Rogers to cool his feet, and sang a song, "There are Many Ways to Say I Love You." Rogers shared his towel with Clemmons and helped him dry his feet.

Different and the Same

In his book, Clemmons shares that throughout his life, he had to hide his sexual preference out of fear for his livelihood and his life. When Rogers discovered that Clemmons was gay, he asked Clemmons to keep his personal life quiet. Clemmons says in his book that Rogers told him that "many of the wrong people will get the worst idea," and he was concerned that Clemmons would be targeted. Clemmons writes that he felt betrayed by the man he looked up to. But he also understood that Rogers was being honest with him about what was then a societal truth.

"When I was young, we had no [role models]. How do you be gay? What is being gay? How is it different? But I didn't know whom to ask."

"When I was writing the book and thinking about a young Black person in 1950, when I was young, we had no [role models]. How do you be gay? What is being gay? How is it different? But I didn't know whom to ask. I didn't have anyone when I wanted to say I don't know what I'm doing. I don't understand this," says Clemmons.

"I wanted a story that was serious, and honest, and loving and positive so it could be an example to a gay fellow whether they're Black, Asian or white," he continues. "I want a young Black fellow to be able to pick up "Officer Clemmons" and say 'oh, he's just like me.' You can live a life of integrity, a life of meaning and caring and be gay."

He listened to Rogers say "You make every day a special day just by being you, and I like you just the way you are" at the end of every show. But in one particular poignant moment, Clemmons knew those loving words were directed to him.

Clemmons is currently working on a second book, and still resides in Vermont. His Kickstarter project will fund an album of American Negro Spirituals, bringing to light the artistic language of his ancestry.

"If we bring love to the table anytime we're negotiating or discussing, we can always solve what looks like a problem or seems like a difficulty if we understand that we are one," says Clemmons. "We're the same."