A Daughter's Story of Her Father's Alzheimer's Disease

Along with neurologist Dr. Bruce Miller, author Cindy Weinstein examines the art and science of the disease that took away her late father's words

For English professor and literary critic like Cindy Weinstein, language means livelihood. Language also means illumination found in the stirring words of her favorite works of literature, such as Herman Melville's "Moby Dick" or the stories of Edgar Allen Poe.

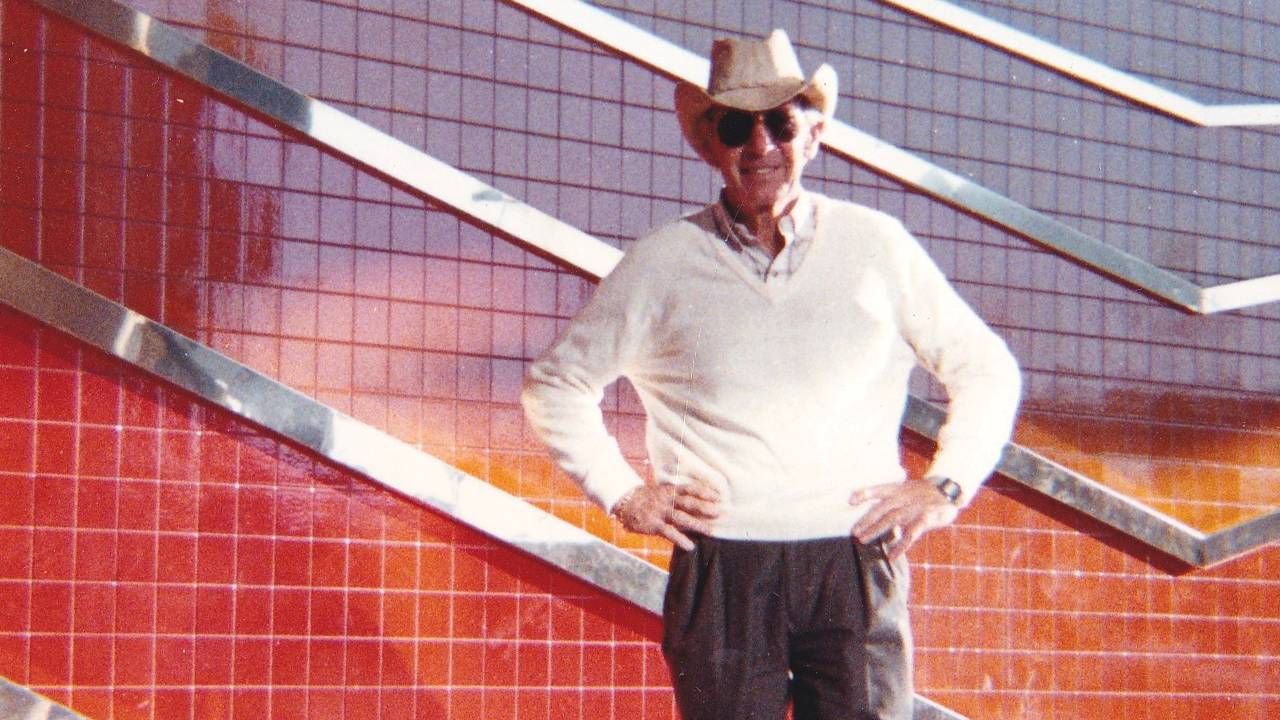

When she was a 25-year old grad student at UC Berkeley, formally pursuing her love of language, Weinstein saw her beloved father Jerry losing the ability to effectively use his own. At 58, he was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer's disease with the logopenic variant, meaning words were literally failing him. His condition grew progressively worse over the course of a dozen years. He died in 1997 at age 70.

Weinstein's new book, "Finding the Right Words: A Story of Literature, Grief and the Brain," was co-written with Dr. Bruce Miller, a neurologist and founder of the Memory and Aging Center (MAC) at the University of California, San Francisco. To write it, Weinstein, who's now 61 and teaches at California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, spent a year immersed in the study of neurology at MAC. And to fully tell the story, she knew she needed an expert, which is how the partnership with Miller (also an avid reader) happened.

"Words were like a colander for him — everything was slipping through the holes and words were going down the drain."

The narratives of the authors alternate in the book. Weinstein tells the story of her father's illness, and how 30 years ago scant information was available to families about this vicious disease. She also tells the story of his life, and along the way, weaves in observations about literature and the insights she has gained from her favorite books.

Miller takes over certain sections of the text offering in-depth explanations of the science behind neurological topics including the brain, Alzheimer's and language.

Next Avenue spoke with Weinstein about this project and about the experience of revisiting memories about her father's life. Following the interview is an excerpt from "Finding the Right Words."

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Next Avenue: You are an English professor and one of your father's first symptoms of Alzheimer's was a loss of language. Did that change your perception of the power of words?

Cindy Weinstein: While it was happening to my dad, all I could do was gnash my teeth. Words were like a colander for him – everything was slipping through the holes and his words were going down the drain. At the time, I thought I could get them back by reading as many books as I could, accumulating as many words as possible.

When I was spending the year at UCSF, I met all of these dancers and photographers who were thinking about dementia in such different terms than had been the case when my dad was diagnosed thirty years ago. There are still ways to access parts of the brain without words. I learned about the power of dance, of music, through muscle memory. The research that is happening in the creative arts relative to dementia gives me hope.

You describe Dr. Miller as someone who studies 'empathy and the brain.' Why is empathy such a valued characteristic for physicians working with Alzheimer's patients and their families?

The person with dementia is the primary sufferer – their family and friends are collateral damage. And it's the primary caregiver who is the one to tell the story. One of the things that goes along with empathy is to listen to what caregivers say. When I was at UCSF, I was able to shadow doctors who were seeing patients with their families and [the doctors] were so responsive — no question was too small or too big. Thirty years ago, we just heard 'goodbye and good luck' from my dad's doctors.

We tend to think of empathy in relation to emotions and feelings, but one of the most empathetic things doctors can do is answer questions. To share knowledge is an act of empathy.

You write about how your father's sickness was 'so loud and awful' and you had to 'drown it out' with (Emily) Dickinson, (T.S.) Eliot and Poe. How did literature soothe you as your dad's condition progressed?

It soothed me in the moment, but there was hell to pay later. I would just sit in the library for hours and hours reading about other people's pain so I didn't have to think about my own. I compartmentalized. It was a winning recipe for doing well in grad school (laughs). It allowed me to keep my mind from thinking of my dad, but that wasn't a good thing.

Tell us about the breakfast that you and your parents shared during a trip to Las Vegas.

My mom and dad used to love going to Vegas. I drove from Berkeley to meet them there for a weekend at a time when my dad was getting worse, before he ended up in a nursing home. He ordered pancakes and the maple syrup arrived in one of those plastic containers with the foil top; he kept turning it upside down, never realizing that he had to open the top.

Time froze. It was such a clear example of what was happening in his brain. I was devastated. I just wanted to burst into tears, but I knew I couldn't lose it. I just helped him open it and moved on.

You compared the process of writing this book as 'sitting shiva' for your father again [a Jewish tradition where friends and family members get together to remember a loved one after a death]. How so?

I had written all my sections of the book except for the introduction – I wanted to take a step back and look at everything. And I realized how much I had forgotten, or refused to look at, over the years. The first shiva we sat for my father after he died was really broken. The rabbi was uninspiring. When you sit shiva, you go around and tell stories, but at that time, it was hard to share happy memories of my dad before he'd gotten Alzheimer's.

I'm not a religious person, so writing this book was like sitting shiva for me, thirty years later. I could tap back into all of the memories of my father and his life.

Editor’s note: This excerpt from "Finding the Right Words" is from a chapter entitled "In Memoriam: Jerry Weinstein."

In the poem “Song of Myself,” [Walt] Whitman famously includes catalogs of things, people, experiences, and visions. Here’s my catalog for Dad.

He smelled of Old Spice. His favorite alcoholic drink was vodka with grapefruit juice. He loved coffee cake. When people asked him his name, he would always say, “Jerald, with a J, not a G.” He was a really good whistler.

On Monday nights, I would go to the bank with Dad. He had these accounts called Christmas Clubs, which I never really understood because we didn’t celebrate Christmas. Sometimes I got lucky, and we got to do my favorite thing at the bank, which was entering the vault.

The woman in charge of the vault would open it and there would be rows and rows of narrow drawers, each containing someone’s special possessions. Dad would have a small key to our drawer and the woman would have another key, and both keys would open the drawer that belonged to our family. A long rectangular box would be removed, and Dad would look through it. I didn’t say anything, just watched. The hush of the place and Dad’s seriousness as he went through the papers lead me to believe that this was all really important, and silence was the appropriate response.

… Here’s more. When my sister and brother got concert tickets to Sly and the Family Stone, he instructed them to get him one too. He didn’t want them to be in Madison Square Garden listening to “I Want to Take You Higher” without being present to somehow ward off incoming dangers—aromatic or otherwise. The way they told it, all of the concertgoers with the exception of my father were standing and screaming to the music, while Dad sat quietly on guard.

He liked “Let It Be,” up until the part when John starts screaming. In the ’60s, at the same time that he started telling people he opposed the Vietnam War, he let his hair grow out, which he had worn in the crew-cut style since serving in the navy during World War II. He took many vitamins and supplements, stopped eating red meat after reading an article on the use of antibiotics in cattle, and ran three miles in Verona Park every day.

He learned how to drive a stick shift when his grade school friend, Hatzi (pronounced Hotsy), told Dad to get in the car and drive. He smoked a lot when he was young, started coughing blood, and quit the habit by throwing his last pack of cigarettes out the car window...

He didn’t like when Mom and Grandma Sarah would be on the phone, and they would suddenly start speaking Yiddish. He felt left out.

He loved Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney movies. Sophia Loren was his idea of the perfect woman. He hated fakers.