10 Years After Alzheimer's Report: Any Progress?

What those who wrote the report and other experts say

Navigating the chaos inside our garage this winter, I stumbled on a box brimming with artifacts from my 40-odd years as a Washington journalist. Staring back at me was the cover of one of those blue-ribbon commission reports, the kind that are collecting dust all over the nation’s capital. But this one, A National Alzheimer’s Strategic Plan: The Report of the Alzheimer’s Study Group. released 10 years ago today, was different. It not only set in motion some important policy changes; it was very personal.

My dad and his mother succumbed to Alzheimer’s, now the most feared disease among people over 65 and second most (after cancer) by all Americans. Naturally, my sister and I, like millions of others in an Alzheimer’s family, have been mindful of the possible genetic links to dementia and whether effective treatments and a cure are on the way.

A Fresh Look at the Alzheimer's Report 10 Years Later

Rereading the Alzheimer’s Study Group (ASG) report made me wonder how much progress had been made since 2009. So I looked into efforts by drugmakers and the government since then and spoke with Alzheimer’s experts, including two members of the report’s blue-ribbon panel, to hear their insights.

Now 10 years after the report’s release, treatments and a cure for Alzheimer remain somewhere in the distance, in part because of two words: “woefully underfunded.” That’s how the report described the federal research investment in Alzheimer’s, which in 2009 was already the nation’s third most expensive disease. At the time, it cost the federal government $100 billion a year.

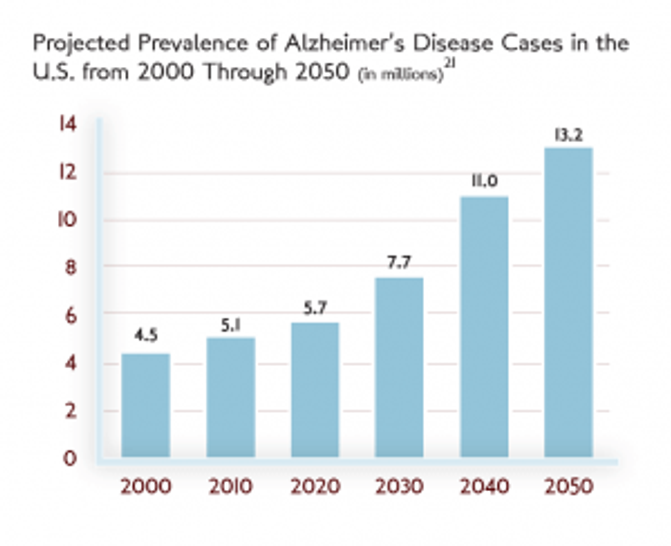

And the report offered this alarming prediction: “If we fail to ...disrupt current trends...over the next 40 years, Alzheimer’s disease-related costs to Medicare and Medicaid alone are projected to total $20 trillion in constant dollars, rising to over $1 trillion per year by 2050.”

With boomers’ aging — the oldest is now 73 and the youngest is 55 —the number of Alzheimer’s cases was projected to jump from 5.3 million in 2009 to 14 million in 2050, threatening to bankrupt the health care system. (When the ASG report was written, the 2050 projection for Americans living with Alzheimer's was lower, at roughly 13. 2 million.)

Putting All the Chips on a Theory

Robert Egge, then the executive director of the ASG and now chief of public policy at the Alzheimer’s Association, says the lack of funding forced researchers to “put all their chips” on the best understood Alzheimer’s theory at that time. That theory: a buildup of beta-amyloid plaques and tangles that are the main brain changes in the disease.

But time and again, all the attempts to convert research into effective drugs to combat or prevent Alzheimer’s didn’t pan out.

“All the pharmaceutical failures we’re seeing are from those bets,” Egge said.

A huge setback came last week. Drugmakers Biogen and Eisai said they would end two late-stage clinical trials of their Alzheimer’s drug aducanumab. The companies concluded that what was hoped to be a promising treatment to slow down the progression of Alzheimer’s wouldn’t help patients.

Doubt on a Leading Alzheimer's Theory

Their decision casts further doubt on the theory that Alzheimer’s is caused by the buildup of beta-amyloid, dashing the hopes of many, including the Alzheimer’s Association, which expressed “disappointment” but tried to put the best face on the news.

“Much of the knowledge we have gained about potential new treatments, and how to properly conduct clinical trials in people with and at risk for Alzheimer’s disease, has been from clinical trials that have not met their endpoints,” the group said in a statement.

Last year, drugmaker Pfizer abandoned its research efforts to discover new Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s drugs and laid off 300 employees. But other companies continue to work on treatments that focus on targets beyond beta-amyloid, such as the protein tau that is also found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients.

Ironically, the same day the dispiriting news broke that the clinical trials of aducanumab failed, there was an optimistic note about Alzheimer's in a Pew Research Survey. More than half of Americans surveyed expect a cure for Alzheimer’s by 2050.

Looking Into Lifestyle Changes to Help Prevent Dementia

In the past decade, while scientists were working on a breakthrough Alzheimer’s drug, there has been a new emphasis on lifestyle changes as one means to help prevent dementia. They include: avoid brain injury, get quality sleep and participate in formal education at any age.

In that spirit, Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine), co-chair of the Congressional Task Force on Alzheimer’s and chair of the Senate Aging Committee, introduced the bipartisan Building Our Largest Dementia (BOLD) Infrastructure Act that was signed into law at the end of 2018. It will establish Centers of Excellence to educate the public on Alzheimer’s, cognitive decline and brain health. The law also directs the federal Centers for Disease Control to award funding to local health departments to support Americans living with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers.

“It’s an attempt to look at Alzheimer’s from a public health perspective, not simply look for a pharmaceutical solution,” Collins says. “They’re both important. But this is an approach to reduce cognitive decline through lifestyle factors and supply more support for families and caregivers.

Betting on New Theories for New Medications

What scientists have learned since the ASG report is that Alzheimer’s disease begins 15 to 20 years before symptoms and that may call for a different strategy than what the blue-ribbon panel laid out.

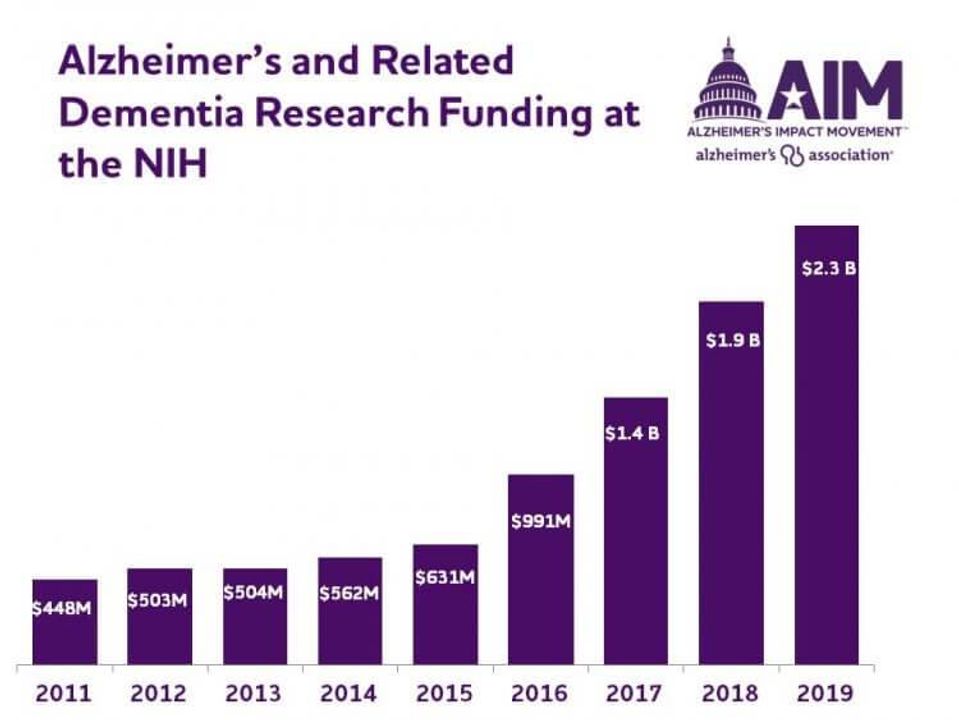

And with National Institutes of Health (NIH) research budgets for Alzheimer’s and related dementia quintupling from 2011 to 2019 (bar chart), Egge says scientists now have enough chips to bet on a whole host of theories increasing the odds of that miracle medication. NIH research funding for Alzheimer's and related dementia research for 2019: $2.3 billion.

The ASG report was released with this warning: “Alzheimer’s disease poses a grave and growing challenge to our Nation. We must act now.” And new statistics from the National Center for Health Statistics only confirm that alarm today: The rate of dementia deaths in the U.S. has more than doubled in the past decade.

What Worries And Encourages Alzheimer's Experts

So, 10 years later, here’s what some of those who’ve been engaged in the Alzheimer’s battle, including ASG panel members, told me are the things that worry them most and where they believe there’s a glimmer of hope:

Former Nebraska Democratic Senator Bob Kerrey, co-chair of the Alzheimer’s Study Group and now Executive Chairman of the Minerva Institute:

“The disease doesn’t get the respect it deserves. There’s one piece I couldn’t get into the report that I believed would be a good thing to do — add a dollar a month to Medicare Part B premiums and dedicate it all to Alzheimer’s research. That would have meant hundreds of millions of dollars. It was seen as a tax increase, so we couldn’t get it done.

The challenge is, given the tsunami of retirees — ten thousand every day turning sixty five — once that cohort reaches eighty, the number of cases and costs could go up sharply.

But I’m hopeful in the enthusiasm I see among researchers at places like Rockefeller University who are trying to find an answer as to what is causing this disease.”

Dr. David Satcher, a member of the Alzheimer’s Study Group, former Surgeon General under Presidents Clinton and Bush and now founding director of Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine. His mother-in-law died of Alzheimer’s and his wife is in hospice after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s 18 years ago:

“I’m worried that not enough people know we have three hundred thousand kids come to the emergency room each year, diagnosed with concussions. We have to realize there’s a relationship between concussions and dementia, not just in professional football but in children. I don’t think we’re giving enough attention to brain health, that includes dementia and Alzheimer’s.

I’m hopeful that attitudes are changing. When NFL players are put out of the game for intentional targeting, this is serious business. But health care providers need to test their patients for memory loss.”

Sen. Susan Collins, who represents the state with the oldest median population and therefore a high incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Collins, a former Next Avenue Influencer in Aging, lost her father to this disease a year ago:

“If we don’t get a breakthrough, I believe the trajectory of this disease is frightening. What it will do to the Medicare and Medicaid programs is equally devastating. Even if one is not moved for humanitarian reasons, Congress should be very concerned about the financial implications.

“What gives me the most hope is the change in public attitudes. Ten years ago, people were still fairly reluctant to talk about Alzheimer’s disease, as though there was shame. It reminds me that people wouldn’t say ‘cancer’ when I was growing up. They called it the “C-word.’ [Public discussions of Alzheimer’s is] an enormous breakthrough, because when people start talking about the disease it helps us advocate for more money that I believe is essential for a breakthrough.”

Dr. Maria Carrillo, chief science officer for the Alzheimer’s Association and former assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center:

“From a scientific perspective, my biggest worry is that across the country, underrepresented populations are not being studied. There are just not enough people of color going to tertiary memory clinics. They stay at their primary care physician... Not only are they not seeing a specialist, but they’re not being referred to clinical studies so we can better understand what’s happening in the disease.

“However, there is a bright side and a huge opportunity. For black and Latino people who have more cardiovascular risk factors, even with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, you can start tackling lifestyle [habits] with high blood pressure, cholesterol and healthy eating, so you may be able to delay or even prevent much of that dementia. That’s exciting and gives me great hope.”

(To learn more about Alzheimer's and get resources that could help you or your family, call the Alzheimer's Assocation's 24/7 hotline: 800-272-3900.)