Can Any Good Come From Alzheimer's?

Some find that relationships among family members heal and deepen

The truth: Alzheimer’s and other dementia diseases are always a burden on loved ones. The lesser-known truth: Dealing with the diseases can provide positive impacts of a temporary or even lasting nature.

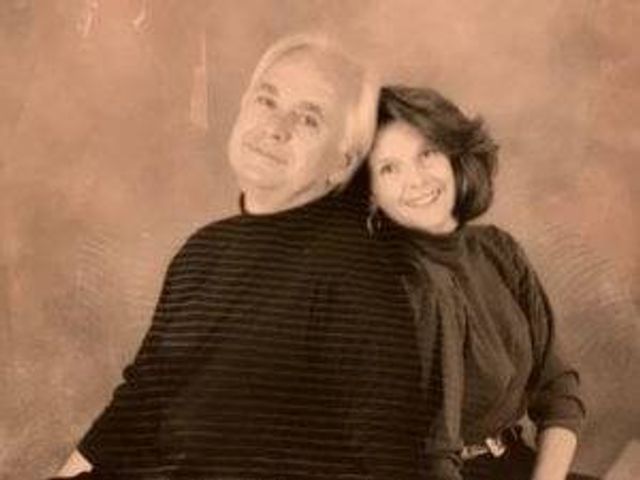

Two sisters, Heidi O’Neill and Amy Springer, both called their late father’s Alzheimer’s “a gift” for the way it repaired and enriched relationships between the two of them and both parents.

“Yes, it’s extremely hard — I’m not going to put lipstick on it,” says Springer, a family-law attorney in Denver. “There were moments when he was frustrated, moments when he was catatonic and he would say he didn’t have anything to give you. But then he would be the kindest, most generous life form I’ve ever seen. I saw my father experience joy every single day, and he fell in love with people and they fell in love with him.”

Before their father, Mickey Mandel, 78, died, in February 2011, O’Neill traveled frequently from her Nashville home to Denver to see him. It was during those visits she experienced first-hand the healing of family rifts — Springer and another sister versus O’Neill and their mom, Springer versus her mom, etc. — that went back to childhood.

"There are two opposing truths: One is that the disease has a very sad end, and the other is that (the patient) can have a full, meaningful life."

“The moment-to-moment love we got to share, just being accepting to where he was [with the disease] allowed us to super-bond,” O’Neill says. “It was just pure connection. Relationships were forever changed and forever better as a result of that. There was clarity and more of a like-mindedness. I don’t feel like we’re coming from two different places anymore.”

For other caretakers, it’s moments that linger.

Katherine Letterman, also of Nashville, experienced her husband, Greg, his mother and both of her parents die of Alzheimer’s within 15 months of one another. But what she took away from all that was almost entirely benevolent, in part, because “there really weren’t unresolved issues (among the family members),” she says.

Still, Letterman found “an opportunity to express love [with her parents] that we knew was there, but was never expressed when I was growing up,” she says.

She also took solace in having her father give up his autonomy and let her care for him, “the true reversal of the parent-child relationship,” she says. “With both Greg and my parents in their decline, I knew the sweetness at the time. It was like watching your children grow up and wanting to cling to every moment because you knew it wouldn’t last forever.”

The Alzheimer's Stigma Can Be Pervasive

Granted, such beneficial outcomes are likely more the exception than the rule. But increased awareness and improved communication around these diseases are helping many spouses and children cope, and sometimes find some light in the darkness.

“The thing with Alzheimer’s is that it’s here, and to be wringing our hands and really focusing on the loss is an absolute disservice and doesn’t provide the caregivers an opportunity to [connect],” says Megan Carnarius, a registered nurse, owner of Memory Care Consulting in Boulder, Colo., and author of A Deeper Perspective on Alzheimer’s and Other Dementias: Practical Tools With Spiritual Insights.

“Yes, it’s difficult. And there are emotions that need to be supported. But [loved ones should] also focus on ‘what can a person still do?’ to be really present rather than getting into anticipatory grief,” Carnarius says.

That grief is an almost automatic response for many people, after hearing what others have said about dealing with Alzheimer’s — generally, it’s had “horror show” written all over it.

That’s unfair to the patient and unproductive for family members, says Leah Challberg, senior program manager at the Alzheimer's Association’s Minnesota-North Dakota Chapter.

“We have a long way to go because of the stigma,” Challberg says. “This is the most feared disease. People (think) immediately (about only) the late stages. The thing I’m always very careful about is to make sure people know that when they are starting to deal with this, there are two opposing truths: One is that the disease has a very sad end and the other is that [the patient] can have a full, meaningful life.”

Working Through the Fog

There’s another two-pronged aspect of Alzheimer’s and other dementias: On the one hand, “One needs to separate that the behaviors are not the person. They are emanating from the progression of the disease,” says Joseph Hunziker, the longtime senior services supervisor at the Magnolia Senior Center in South San Francisco, Calif.

The other aspect, Hunziker says, is that the loved one with the disease really is “in there,” even when confusion and anger are temporarily reigning. The fog of dementia often means low visibility rather than no visibility — and that fog can break at any moment. As Challberg also notes, “the brain’s ability to transmit who they are is always there.”

That’s why, Carnarius says, “holding in mind the whole person is important because people have lucid moments when you go, ‘Oh, it really makes a difference in what they show you.’ They’re trying to tie things together before they go, trying to reflect from different eras and deal with unresolved things.

“It’s so important that the person being around [the patient] not be dismissive,” she adds.

That can be exceedingly difficult when dealing with the frequent irritation or outright ire from the Alzheimer’s sufferer, not to mention what Hunziker calls “watching your loved one fall apart in front of you.”

Still, there are those moments. “Sometimes people have found that the gruffness goes away, and they can connect more with the tender side of their parents than they ever have,” Challberg says.

So, it’s important to stay in the present. That was key for the positive experiences O’Neill and Springer shared, growing closer to both parents and each other.

“It would have been horrible,” Springer says, “if every day my mind circled back to how he used to be. There was not a moment of that.” Instead, she says, she reveled in her father’s state of mind, even as his mind was fading.

“He experienced joy every single day, and I got to be there,” she says. “I was surprised I never got a speeding ticket when I went down to see him because I was so excited.”

4 Tips for Loved Ones

- Get some backing: “The people I meet with who are best able to deal with this have put together a significant community of support,” Challberg says. The Alzheimer’s Association also has support groups and community-education opportunities.

- Practice loving kindness: “You need compassion, forgiveness and the ability to be respectful when dealing with a person screaming, hitting at you, lashing out,” Hunziker said. “It sounds simple, but in the moment, it’s not easy.”

- Look for the levity: Challberg has observed people being “able to laugh with the person about how bizarre and silly something is. They can have some moments of playfulness and joy and fun even as the disease progresses,” she says.

- Be attentive: “How do we train our eye to see the things that are positive? If you’re ready for it, you see it,” Carnarius says. Adds O’Neill: “The miracle of this disease, the thing that people with dementia never lose, is the ability to connect with the person in every moment.” As Challberg notes: “They’re always communicating.”