Finding Healing After a Spouse’s Death

‘The Widower’s Notebook’ examines the impact of his wife’s sudden death on his life

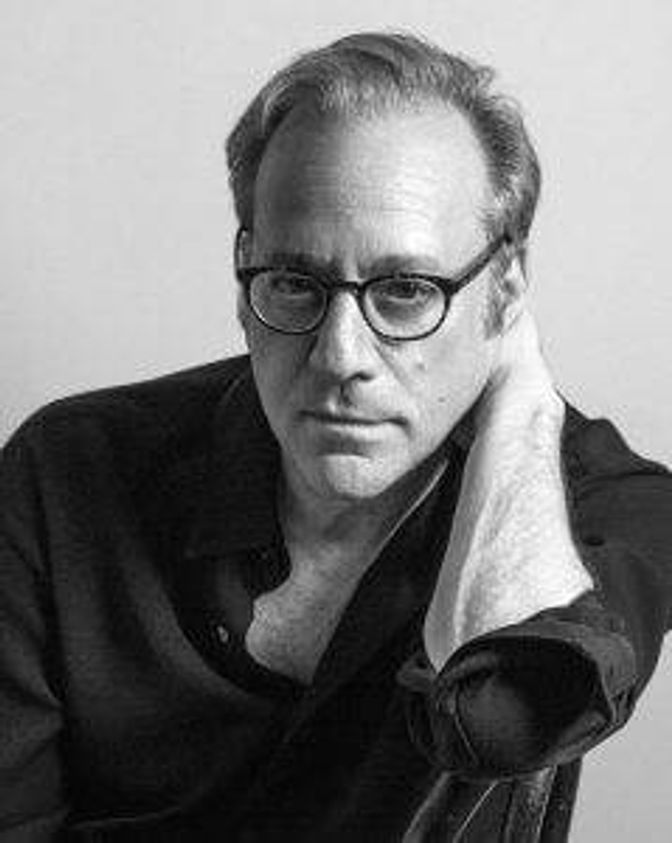

Before "The Widower's Notebook" became an eloquent and poignant memoir, it was six composition-style notebooks filled by the novelist and artist Jonathan Santlofer in a nightly practice which he says "kept him grounded" at a time when he felt wholly "disconnected" and submerged in grief.

Santlofer, the author of crime novels including "The Anatomy of Fear" and "The Death Artist," had never kept a journal, but found himself leaning on those pages to record, by hand, his overwhelming feelings of sadness, loss and loneliness in the wake of the sudden death of his wife, Joy, in August 2013, just a day after her outpatient surgery for a torn meniscus.

Joy had reported feeling feverish and "congested" to her doctor's office, and the staff seemed unconcerned; she was simply told they'd see her at a follow-up appointment in a few days. But just hours later, Santlofer's world was irrevocably changed amidst a chaotic scene in their New York City apartment when paramedics arrived following a frantic 911 call after Joy lost consciousness.

He writes: I watch, a helpless man observing from the sidelines, though I see it in detail, every second of it becoming etched in my mind's eye, an endless movie loop, which later will become readily accessible at the flip of a synaptic switch, never something I do voluntarily but always with me and playing too often.

On that devastating day, Santlofer, now 72, became a widower and embarked on an emotional journey that he never expected.

'Someone Who Didn't Need Help'

"Before Joy died, I always felt I was a cool, independent guy," said Santlofer in a recent interview. "I discovered I wasn't that guy I thought I was."

Growing up with "a post-war, very tough" father, Santlofer admitted he generally found it hard "to ask anyone for anything, in an almost extreme way" throughout his life.

"People always perceived me as someone who didn't need help. But it's a bad thing for people to assume that, and it took me a while to figure that out," he said.

And in the years Santlofer has spent slowly making his way through grief, he has discovered this is a common trait among men who don't know how to ask for help as they struggle with loss.

"[Since the book came out], I hear from strangers almost every day, and more than half are men. They'll write something like 'Thank you for finding the words to write that I could never say,'" he said.

The Role of Friends

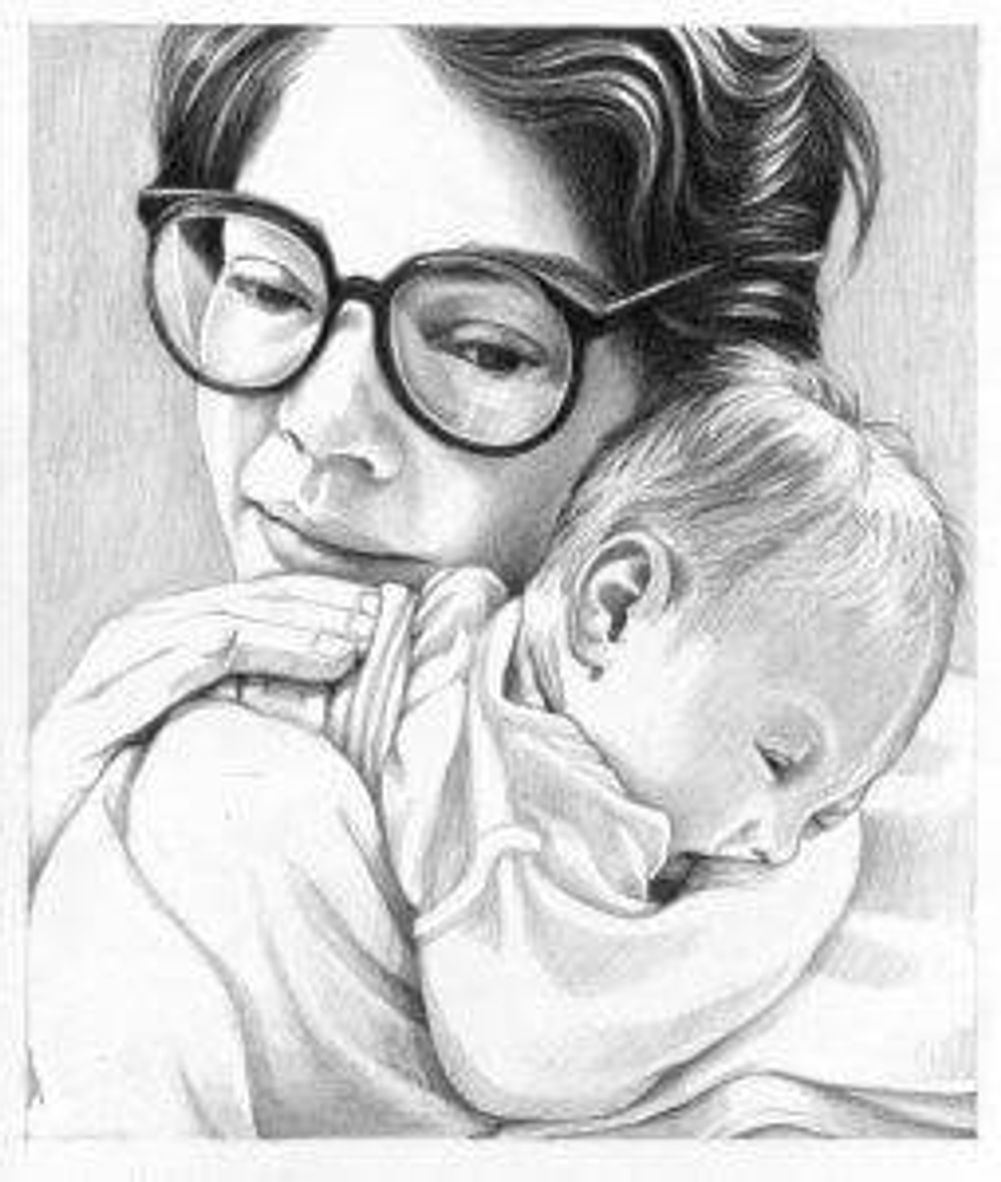

"The Widower's Notebook" details topics ranging from Santlofer's sleepless nights for months after Joy's death to happy memories of their 40 years together and of their daughter Doria (including the course their father-daughter relationship takes without Joy). Santlofer also writes about the pain of living alone, how he and Joy's cat, Lily, finally made peace, the heartbreak of cleaning out Joy's closet and the frustrating runaround trying to get information about the exact cause of her death.

Santlofer also examines the role that friends played as he tried desperately to adjust to his new normal.

"The friends I expected to rally around me in the best possible way didn't," Santlofer said. "Some of Joy's and my friends disappeared completely on me."

Others approached Santlofer's new status as a widower in sometimes shocking ways. He relayed a conversation with a now-former friend, who asked him point blank, a year after Joy's death, "Haven't you gotten over that yet?"

In talking with other men and women who have lost a spouse, Santlofer has learned unexpected reactions from friends aren't uncommon. But as the months after Joy's death went on, he was also surprised to discover that widows and widowers are treated very differently in social circles.

While widows he knew also reported being routinely "dumped" by other couples, Santlofer was frequently invited to social events where he was obviously being set up for dates, without his knowledge; a practice he called "flattering, but weird" and generally unwanted.

In his book, he writes: Losing your partner is a litmus test. It brings out the best and the worst in people; it provokes good, bad and unpredictable behavior. I have seen it make people sad, scared and incredibly insensitive. Odd, that at the moment when you are at your most vulnerable, you are subjected to other people's fears and their vulnerabilities.

As he says now, "At this point, I forgive everyone. What I tried to impart in my book is just how important it is to show up for someone."

The Power of Drawing

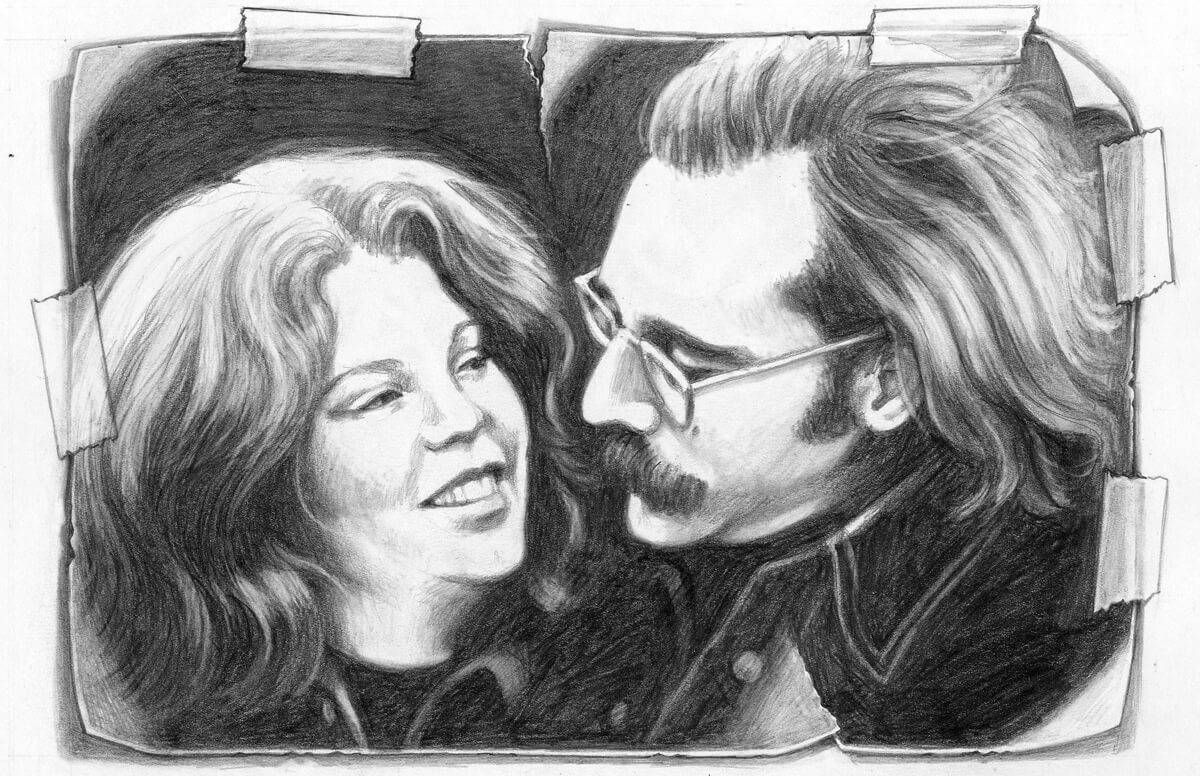

The illustrations in "The Widower's Notebook" are just that; Santlofer's sketches of Joy, the two of them together and their daughter, which illuminate the text in an especially meaningful way.

"It was very important to me not to use photos in the book — I felt very strongly about that," said Santlofer, who began his career as a visual artist, and has had his work in many public and private collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

In the book, Santlofer writes about putting away photos of Joy because, initially, they were too painful to look at. Slowly, he begins to want to draw again and starts with a printout photo of Joy that he finds on her computer (she was finishing her own book, "Food City: Four Centuries of Food-Making in New York," at the time of her death, a book that Santlofer and others shepherded to publication and was a 2017 James Beard Award nominee):

I am able to draw my wife because drawing is abstract, because you can't really draw something until you stop identifying it…Drawing has made it possible for me to stay close to Joy when she is no longer here. It is a way to create a picture of her without feeling weird or maudlin. I am not sitting in a dark room crying over a photo of my dead wife, I am at my drawing table, working.

Santlofer says having that creative outlet was a balm during those first years. "I did almost 80 drawings. Some I crumpled up and threw away. I drew almost every day and it was very helpful to me," he said, adding that his publisher chose the ones featured in the book.

Grief Is Universal

Santlofer has come to realize that grief "is a permanent part of who I'll always be." From the first year spent in "a cloud of fugue" to the second year, which he found to be even worse, Santlofer thinks he has finally arrived at that new normal.

"I write about this in the book, but I had a friend who, more than three years after Joy's death, referred to me as 'full spectrum Jonathan,'" Santlofer says. "But really, I'm a new full-spectrum. I don't think I'll ever fully be the same person I was. I have been affected by Joy's death in profound ways that have changed me."

Although initially concerned about the emotional toll it would take to promote The Widower's Notebook in appearances across the country, Santlofer now calls meeting so many readers who could relate to his experience "remarkable."

From a bookstore event in Phoenix, where a hospice director and a rabbi brought their staff members, 150 total, to hear his presentation, to quieter interactions where "people would fall against me, crying," Santlofer has seen first-hand how his personal story of one man's grief is a universal one.

"I hear from people all over the country who are telling me intimate things about their own lives and their own loss," he said. "This is not just a book. We've become correspondents, and I feel that there is something beautiful in that."

Santlofer is currently finishing a novel, and is working on nonfiction proposals, including a book on men and friendship.