How an Autism Diagnosis as an Adult Can Change Everything

After years of confusion and hardship, the news puts much into perspective

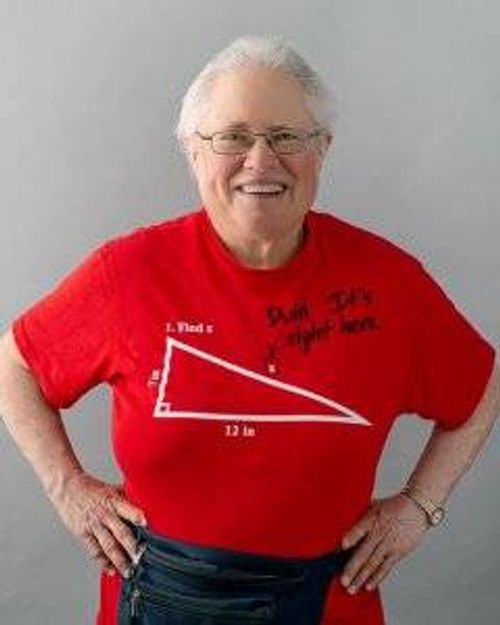

Relief. That’s a common reaction among people who are diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) when they are adults. Assessed in her late 40s, graphic artist Barbara Moran, of Topeka, Kansas, says her diagnosis finally explained why her life had always seemed so “out of sync” with others.

Moran, now 67, tells her story in Hello Stranger: My Life on the Autism Spectrum, a book based on conversations author Karl Williams had with Moran and her family. In an interview with her publisher, Moran says that for years, she had felt shame.

“Being diagnosed with autism was like being forgiven,” says Moran. “My problems weren’t character faults; they were legitimate complaints. It was like the ugly duckling learning he was a swan.”

Dr. Marjorie Solomon, professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of California-Davis, gets that. “People who never felt like they fit in, people who have been considered weird or quirky or who had what they thought was a personality disorder so often have a sense of relief when they find a label that fits them,” she says. “A diagnosis of ASD helps explain a lot of mysteries, makes sense of pieces that never fit together before.”

Solomon also is a faculty member at the university’s MIND Institute, an international research center in Sacramento, Calif., that investigates neurodevelopmental disorders, and teaches in the postdoctoral autism research training program.

‘A Lot of People Have Gotten Lost’

“When I started working in this area 20 years ago, the thinking was that 75% of people with autism had mental retardation,” Solomon says. “Now, that percentage has flip-flopped and we say these individuals have ASD. In the course of the switch, a lot of people have gotten lost.”

Moran was “lost” for several decades. Repeatedly defined as “undisciplined” by her teachers, in 1961, she was sent to live at The Menninger Clinic, then located in Topeka (it is now located in Houston). There, because doctors did not yet know that ASD is a brain development disorder, the 10-year-old girl was told that she had made a choice to be mentally ill.

The term “autism” was first used around 1911 to describe symptoms of schizophrenia. In 1943, Dr. Leo Kanner adopted the term to describe children with a range of behavioral problems recognized today as typical of ASD. By the 1950s, Dr. Bruno Bettelheim began to publicize Kanner’s work, blaming autism on “absentee parenting.”

At the time of Kanner’s work, Dr. Hans Asperger also was studying children with behavioral problems, but his research was overlooked for three decades. (For more on the history of the disorder, see Steve Silberman’s book Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity.) In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association combined subcategories of autism and related conditions into one unified category: ASD.

Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder

High-functioning adults with undiagnosed ASD often develop compensatory social skills so they can behave more typically in public. ”But when pushed into situations where they can’t navigate, when they are under extreme stress and their abilities are overtaxed by environmental demands such as a new job, getting a divorce or being fired, eccentricities may come forward that indicate hidden ASD,” Solomon says.

Those behaviors could include:

- Difficulty with social relationships

- Inability to see others’ perspectives

- Sensory issues with sounds, smells or being touched

- Physical tics

- Intensely focused interests

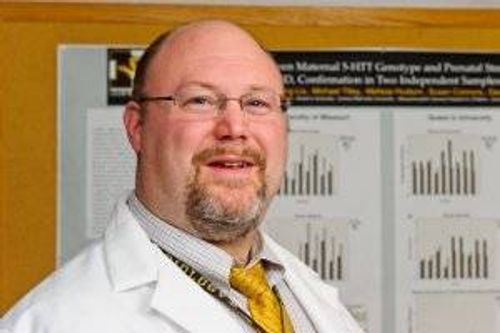

Neurologist Dr. David Beversdorf recalls a couple in their mid-60s who met with him after the husband retired and the wife noticed some odd behavior patterns. “I told them I thought he likely was a high-functioning individual with ASD, and I recommended counseling so the wife could better understand her husband’s situation,” Beversdorf says.

He teaches at the University of Missouri’s Thompson Center for Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Columbia, Mo., where his research focuses on autism, dementia and the cognitive effects of stress. Beversdorf is affiliated with Autism Speaks, an advocacy group that offers a tool kit to help adults determine whether to make a doctor’s appointment for an assessment.

Undiagnosed, Life Can Be ‘Frustrating and Depressing’

The tests for autism, Beversdorf says, are designed for children and do not always transfer well to adults. “It’s tricky, because this is a new area of study, and there are only a handful of things out there in regard to adult diagnosis and management,” he says.

He adds, “There is some evidence that a large proportion of increased diagnoses among adults is not an indication of increased incidence, but to a large proportion, one of recognition. When ASD is unrecognized, individuals’ lives can be frustrating and depressing, and they don’t understand why — and that’s hard.”

That was the case with Peter Street, who was diagnosed with ASD at 67. He says his reaction to his diagnosis was one of “enormous relief” because “all my life suddenly made sense.” Street lives in the Lancashire town of Wigan, in England, and his story was reported in a 2016 article by John Harris in The Guardian, an international publication.

In the article, the National Autistic Society estimates that some 700,000 people are living with autism in the United Kingdom, or more than one in every 100. “The British Health Service’s statistics may not apply to the U.S.,” Beversdorf says, “but probably the number of people living here with autism is not a small percentage. It’s not infrequent that I stumble across someone who has never been assessed.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that more than 3.5 million Americans live with ASD.

Finally, 'A Better Life'

Eventually, Barbara Moran was recognized by her health care providers at The Menninger Clinic as a “high-functioning” individual and was allowed to attend public school. Later, she was placed in foster homes with families hired by Menninger’s. Today, she lives on her own. She has spoken at autism conferences, and her artwork has been exhibited in several shows.

“At Menninger’s, I was in the best place as far as institutions are concerned, but mental patients are not listened to. They are told what is best for them,” Moran says. “Today, autistic people can have a better life if they get the kind of help they need.”