Being Atticus Finch

A sentimental journey to an icon of American literature and cinema

"The one thing that doesn't abide by majority rule is a person's conscience."

– Atticus Finch, "To Kill a Mockingbird"

Entering Monroeville, Alabama, from the south on Highway 41, there are few hints — except for a lone sign declaring it — that we've arrived at the "Literary Capital of Alabama." There's a WalMart Supercenter on the right, up ahead on the left is a factory making precast concrete slabs and hovering in the air, the unmistakable aroma of the local pulp mill. Another sign urges us to "Shop, Eat, Stay & Play." But we're on a mission.

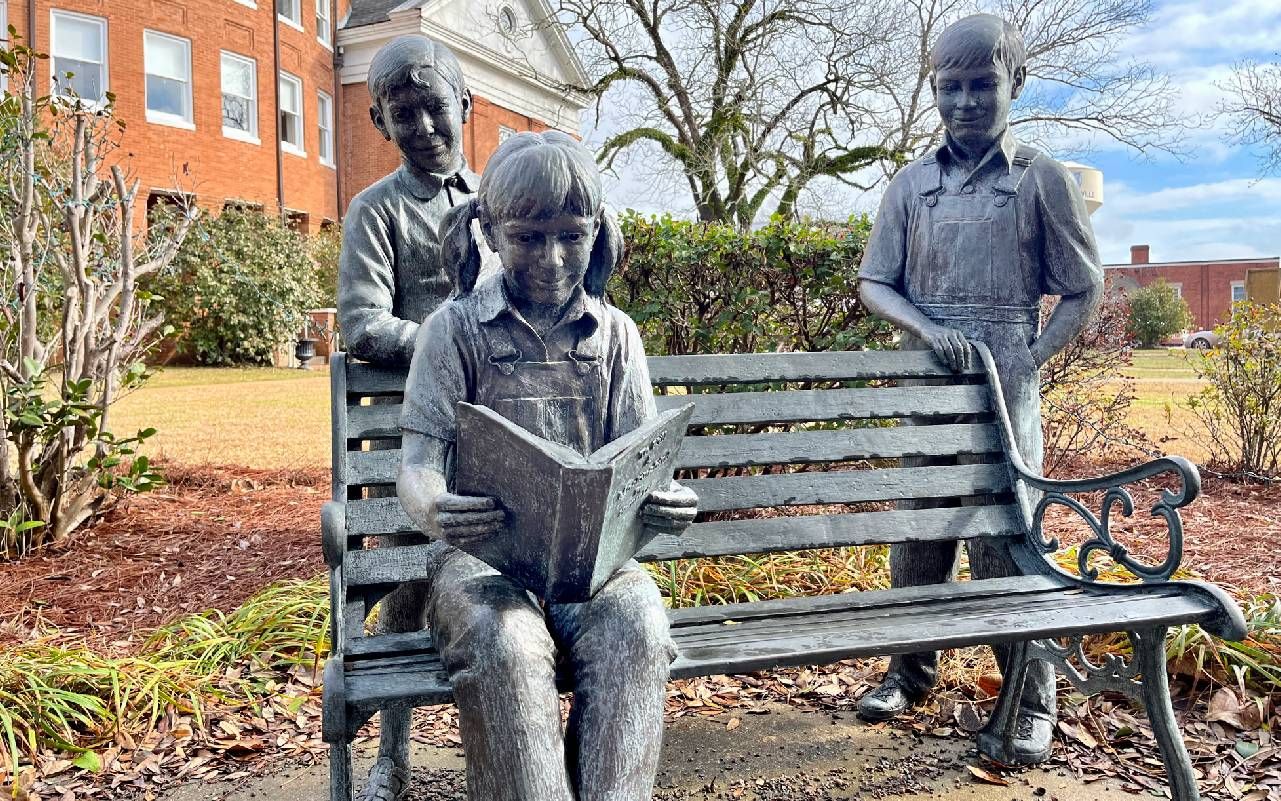

Not until we've nearly arrived at the town square does the object of my obsession rise into view. The Old Courthouse dominates the square. It could be the centerpiece of any county seat in America, but this one holds the Holy Grail for this pilgrimage.

We go up a flight of stairs and through the double doors and — like Howard Carter cracking open Tut's lost tomb — there it is: the very courtroom where Nelle Harper Lee's childhood experiences became the inspiration for "To Kill a Mockingbird," her 1960 masterwork that still tops lists of the most popular books in the nation. In 2018, PBS viewers voted it the #1 "best-loved novel" in the Great American Read competition.

"People don't just end up here, they are coming here."

The Old Courthouse is now a museum dedicated to Lee, her work and her childhood pal, Truman Capote. The two of them are the foundation for Monroeville's "literary capital" claim. In the vestibule is a U.S. wall map jammed with multicolored push-pins placed by visitors, once estimated at about 30,000 a year, or five times the city's population — pretty good for a little burg that's not really on the way to anywhere.

Destination Mockingbird

"People don't just end up here, they are coming here," says Rhonda Burch, a retired teacher who is now the museum's education director. "It's a destination. It's amazing to me; we're so far off the interstate."

The Old Courthouse may have "sagged in the square" in Lee's memory, but it provided inspiration for director Robert Mulligan's adaptation of the novel. "They actually fell in love with the town and wanted to film the movie here," Burch explains. "But the town had changed too much because the book was set in the 1930s."

So, production designer Henry Bumstead spent whole days measuring and sketching the old courtroom for his meticulous reproduction on a Universal Studios soundstage. Standing at the counsel's desk near the jury box, I could almost hear Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch mounting his defense of Tom Robinson, the Black man falsely accused of assaulting a white woman. I could almost see the Finch children, "Jem" and "Scout" peering over the rail from the balcony. It was like being in church.

Some have traveled much farther than I for the experience. Among the pilgrims, says Burch, was a Japanese tourist who rode a bicycle the 90 miles from Mobile to be able to say he was here. Burch ticks off the list of inspired pilgrims. "Lots of lawyers who are lawyers because of the movie, some people named Atticus, some people named Scout."

Harper Lee's Presence Still Felt

Outside the town square, little remains of the neighborhood of Scout's adventures. The Lee home on Alabama Avenue is gone, replaced by Mel's Dairy Dream, a drive-up ice cream stand. The Faulk house next door, where Truman Capote lived for about six years as a boy (the prototype for "Dill," the scrawny kid next door with a penchant for embellishment), is an empty lot with a roadside historical marker and stone wall remnant. There is no sign of the "hole in the tree," or the tree for that matter, where the reclusive Boo Radley left soap figures and other trinkets for the Finch kids.

Nelle Harper Lee died in 2016 but she remains a powerful presence in Monroeville.

Janice Sawyer, 60, has vivid memories of when Nelle and her sister, Alice would frequent Sawyer's Courthouse Cafe, across the square from the courthouse. "They loved potato [salad] and chicken salad. That was two of their favorites," Sawyer recalls. "I did Miss Alice's cake when she turned a hundred for her birthday."

Sawyer still leverages the seemingly inexhaustible Mockingbird fandom. Her menu features an assortment of "Boo Burgers," offered with a side of "Finch fries" (and presumably a "Dill" pickle). Eighty-three years since the book's publication (81 since the film release), she doesn't think the fascination with Mockingbird will ever die out entirely. Out-of-town customers are still hungry for more than Boo Burgers. "They wanna know every little detail," says Sawyer. "'We wanna ride by their house. We wanna see where they lived.'"

Locals retain a certain reverence for the Lee family. As Casey Cep wrote for The New Yorker in 2015, "the Lees were an ocean, and the people in town always waded in slowly, retreating whenever they went too far."

The shadowy figure of Arthur "Boo" Radley was also based on a real character from Nelle's youth. Played by a very young Robert Duvall in the film, his heroism in the climactic scene would cause Atticus to shake his reluctant hand and say, "Thank you, Arthur. Thank you for my children," in another of the film's many heartrending moments.

Rite of Spring

The Mockingbird mania reaches its apogee every spring when the all-volunteer Mockingbird Company stages a dozen performances of the story, in the original courtroom, from mid-April to mid-May. While the town has added a rodeo in recent years, the plays are by far the biggest draw.

While Mockingbird remains one of America's best loved novels, it has never been able to shed controversy. The American Library Assn. listed it among the top 10 "Most Challenged Books" of the past decade, reflecting complaints made about its presence on library shelves, most often for "racial slurs and their negative effect on children," having a "white savior" character and for its "perception of the Black experience," according to the A.L.A. It's in good company, alongside books by Toni Morrison, Mark Twain, John Steinbeck and Alice Walker, to name a few, that also appear on the list.

I can only speak to my own experience. Lee's beautifully woven story has haunted me since I first saw the film on TV, not many years after its 1962 release. When I read the book, it became my lifelong favorite. There are moments and lines that still put a lump in my throat.

"You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view,"

While Atticus was an idealized version of Lee's lawyer-father, to me his character represents a standard of common decency, of civility that seems in short supply several generations hence.

In these times in particular, when hate has cast off all of its various disguises, I see Atticus and his struggle as a bulwark against injustice and inhumanity. As he famously counseled Scout, "You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view ... until you climb into his skin and walk around in it."

An inspiring visit deserves a fitting epilogue, which occurred as we were climbing into the car to leave. Just outside the courthouse door, flitting among the upper branches of a towering pecan tree were two mockingbirds. They must've felt at ease there because as everyone in Monroeville knows, it's a sin to kill a mockingbird.

Read More