When the Music's Over: My Brother and Me

Reflecting on the silly squabbles Jerry and I had, and our last days together

I had read somewhere that, upon first listen, the guitar solo on Steely Dan's "Reelin' in the Years" knocked Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page off his chair. That couldn't have been easy, and so I figured this was just the material I'd need to fire back at my older brother, Jerry. Surely, those were qualifying riffs.

"What's the best guitar song ever?" Jerry had challenged, when he and I were visiting Mom, who'd been ailing, in her house in 2018.

We had lived separate lives in different cities for decades. At the same time, though, I knew we were avoiding the big conversation; the reason I was back in town.

As kids sharing a bedroom decades ago, we talked about such things countless times. The idle discourse carried over to our adult years, building on our family's love of a good meaningless assertion and the ill-informed discussion that followed. Jerry seemed to enjoy engaging this way more than the rest and had no time for anyone who searched Google to cut short a rollicking, pointless debate.

But the guitar solo question was different. Page had handed me bulletproof evidence of greatness, which I'd need because music — or more precisely, rock 'n' roll — was my brother's passion. This was his wheelhouse.

Jerry had a thousand albums, read every issue of Rolling Stone cover to cover, and placed them on a shelf near his vinyl collection. For a time, he made his living as a radio disc jockey.

Arguing Over Rock 'n Roll

The most innocuous claim about the music he loved might rile him like a sports fan whose team lost on a bad call. I enjoyed pushing back, as a little brother might. But I knew better than to push too hard. Nothing good would come of it.

"That's a good one," Jerry said upon my nominating the 'Reelin' in the Years' solo. "But there are so many better ones. Seriously. And don't give me the Jimmy Page argument. I don't believe a word of it."

"Fine," I said. "Creedence. 'I Put a Spell On You.'" That was one of Jerry's favorites going way back. We had played air guitar to it hundreds of times.

"Love that song," he returned. "But wrong. It's not even Creedence's best guitar song, much less one of the best of all time. 'Born on the Bayou,' Dude."

"Wait, you are saying 'Bayou 'is one of the all-time great guitar solos?"

"No, no, no. But it is John Fogerty's best. Hey, don't move," Jerry said.

He got up and started for the living room, which he had claimed for his record collection and audio equipment. As Jerry walked away, he slumped and seemed tired. I wished I hadn't said anything that made him want to stand up and fetch proof of his position.

In minutes, he was back clutching the May 30, 2008, issue of Rolling Stone. The magazine was already opened to a story headlined "100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time." It had "Bayou" as No. 53. No other Creedence song made the list.

We sat together a while longer, poring over songs at the top of the list and discussing their merits. Clapton, Hendrix, Prince, Page. We hadn't talked like this in years. We had lived separate lives in different cities for decades. At the same time, though, I knew we were avoiding the big conversation; the reason I was back in town. His stage 4 esophageal cancer.

I was not going to go there first. At last, Jerry changed the subject. "This is all great fun," he said. "But guitar solos aren't really all that important, are they?"

Jerry's Health Takes a Serious Turn

Jerry removed the baseball cap I'd sent him two weeks earlier. It was the first time I saw him totally bald. Somehow, that was more jarring than the 35 pounds he had lost.

"I can't believe how fast this hit me," he said. "The good news is the chemo seems to be working. The lump in my throat has shrunk and I can eat again."

It had been a year since Jerry moved in with Mom, then 88, so he could care for her. It now appeared more likely that she would end up caring for him.

Jerry had yet to be diagnosed. He hadn't even seen a doctor. Jerry hated doctors the way Mark Twain hated hospitals — too many people die there, Twain purportedly said. But he must have felt the cancer at a subconscious level. I recalled how little he ate that night we were together, and how slowly he swallowed.

Jerry, at 64, handled his illness like a champ. While I was off in New York City pursuing a writing career, he had chosen to keep life simple by staying near home in St. Louis. But in so many ways, he was stronger than me.

I would have broken into a million pieces had I been the one who'd developed near-certain fatal cancer. Jerry quickly seemed at peace with it all.

I had seen his resignation before — when Jerry's first wife passed of breast cancer 25 years earlier. Sitting with him at her funeral, I was the basket case, not him. I'm not sure where he found his strength.

As an atheist, it certainly didn't flow from faith. The source, I believe, was that he didn't expect much out of life and took whatever came his way in stride. He liked things simple. He was content, no matter what.

"Do you think about what comes next?" I asked that day.

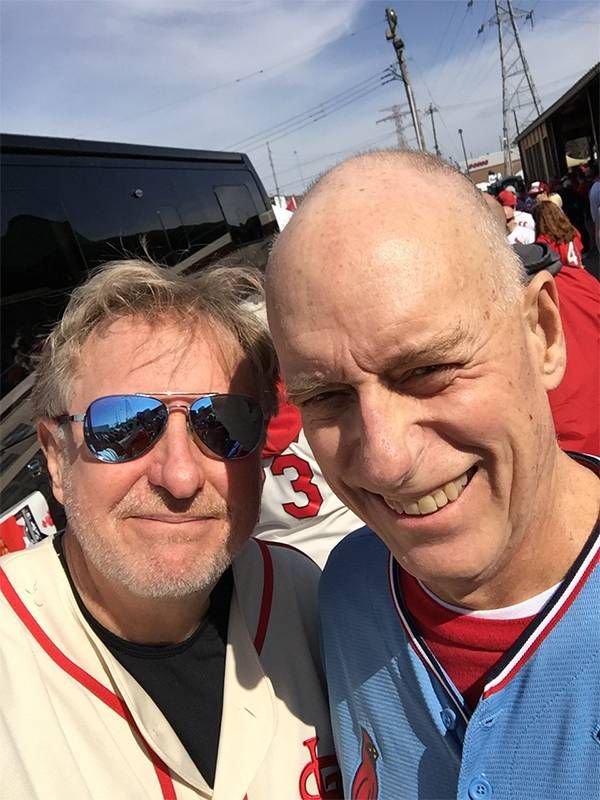

I visited Jerry and Mom more often in the months after his diagnosis. We went to a baseball game on a day when his energy was good.

And I sat with him at the hospital, as a nurse pumped his veins full of epirubicin, cisplatin and other unpronounceable drugs that comprised his chemo treatment.

Talking With an Atheist About What's Next

"Do you think about what comes next?" I asked that day. "It's not too late to pray."

We were going to be sitting there for hours. We had to talk about something.

"You know I don't believe in God," Jerry answered. "It would be kind of hypocritical to start praying now. Don't you think?"

This is no time to be principled, I thought. But I did wonder how he thought about his own mortality with such a terrible cloud hanging over him.

"Look Dan, I can't lose," he said. "If there is no God, I'm right. If there is a God, he or she will be forgiving, and I'll get into heaven anyway. It's not like I have been a bad person."

Other than rock 'n' roll, Jerry's faith seemed to be that whatever the outcome — heaven or not — he'd be okay with it.

I couldn't decide if this was genius, the product of years of solemn contemplation on a mountaintop or an excuse to not think about it at all. But I was happy for his peace of mind.

The second time I sat with him at the hospital, the chemo clearly had exhausted him. My heart was heavy, and I just wanted to make his day brighter in some little way.

"Do you have a bucket list?" I asked. "Is there anything you want to do?"

His Bucket List and Mine

I hoped he had a burning wish, one that we could dream about together for a few hours and that I might possibly help make come true. Did he want to see Alaska? Go to the Super Bowl? Swim with dolphins? Walk the Great Wall?

No, wait. Those were things that I wanted to do; in fact, had done. Jerry wasn't me. He liked things simple. Why was that so difficult to accept?

"Not really," he told me. "I just want to relax at Mom's pool, barbecue, maybe go to a few ballgames and spend more time on the boat."

The boat wasn't a real boat. It was a floating casino on the Mississippi. Jerry and Lisa loved it there. Accompanying him to chemo, I learned things like that. Little things that I didn't know.

"What about you?" Jerry asked. "What's your bucket list?"

The question surprised me. I wasn't the one with stage 4 esophageal cancer. I wasn't the one under a death sentence.

It's not like I never thought about things I still wanted to do. But I have been fortunate enough to do bucket list things somewhat regularly.

The answer was right in front of me.

"You are my bucket list," I said. "We've lived separate lives for forty-five years. I always thought that in our sixties and beyond, we'd have time to connect more often. I don't need to travel. I just want more time with you, and I am afraid I am not going to get it."

I was near tears. Jerry seemed stunned, like the idea of reconnecting in our retirement years was something he could not imagine me wanting.

Had we grown that far apart? Had distance and time erased a bond forged as kids sleeping three feet apart and chatting into the night?

There was a moment of silence. Then he smiled.

"Thanks for saying that," he said.

Goodbye to Mom and Jerry

I'm not sure Jerry appreciated the extent to which his illness was happening to everyone around him — not just to him. His wife and son most of all. Mom certainly. The thought of burying her son more than saddened her; it hastened her decline.

Jerry's first round of chemo ended in early summer; his hair and some pep returned. But Mom fell gravely ill right then, as though she sensed an opening to say her last goodbyes.

It was like Mom and Jerry had made some kind of deal with a higher authority.

Jerry's cancer had taken its toll on her. In her last moments on Earth, though, her son Jerry was getting better and good things were possible.

Mom's turn for the worse, then her funeral in August and then the estate issues that fall onto children after the last parent passes took our minds off Jerry's cancer that summer.

He was putting on weight. His hair was back. He was doing so well that he took charge of the sale of Mom's house and disposal of her possessions. His illness was so out of mind, we allowed ourselves to be ourselves again and even butted heads a few times over who got what out of Mom's house.

But you don't come back from stage four.

Jerry's "recovery" was short lived. Only weeks after Mom was gone, his cancer came back with pronounced determination. It was like Mom and Jerry had made some kind of deal with a higher authority. His illness took a breather so Mom could pass in peace, and now it was Jerry's turn. He didn't have to fight any longer.

I sat with Jerry in hospice for a week, watching him fade. Anyone who has witnessed the agonizing deterioration of a loved one knows it is a peerless life experience. We spoke very little, certainly nothing of guitar solos.

But I can't hear a great riff now without thinking of Jerry. While this inevitably saddens me, I am thankful that his passion for music, and a good pointless discussion, will forever keep us close.

(This article is adapted from one that originally appeared on Medium.)