Her Parents Survived a Bombing and an Internment Camp. Now She’s Their Caregiver.

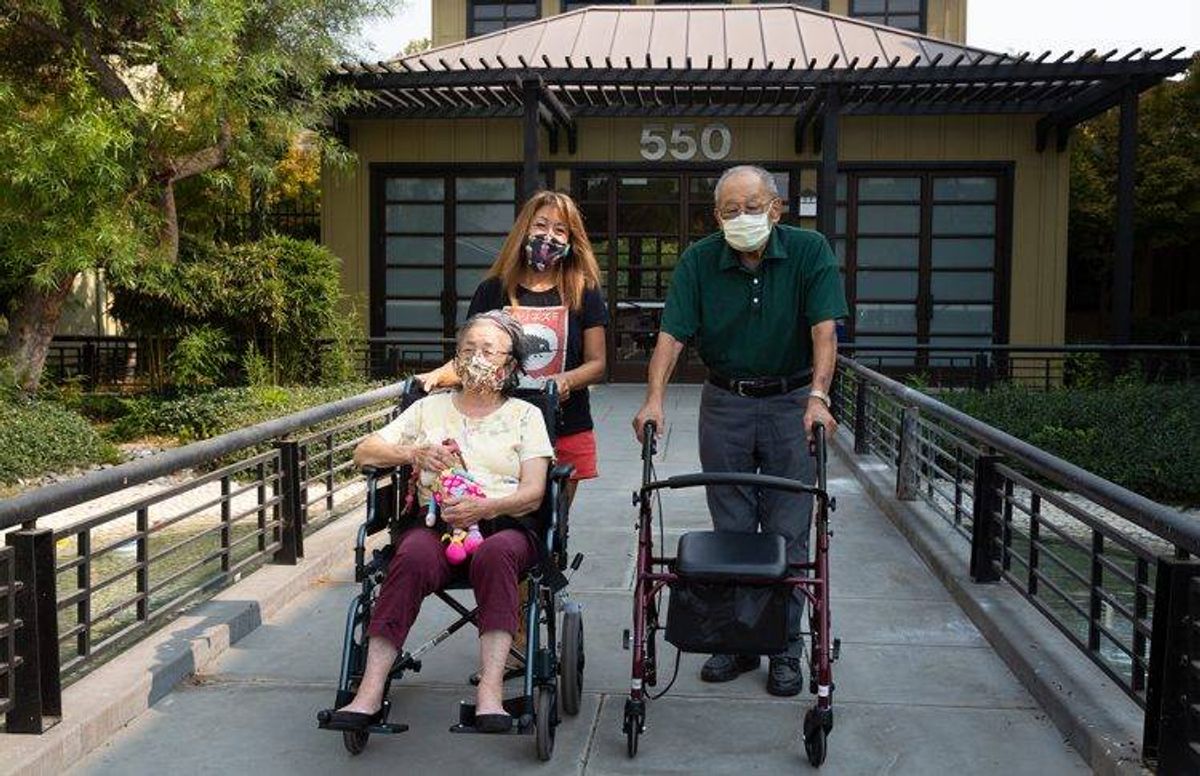

In San Jose’s Japantown, June Yasuhara learns more about her parents’ dementia daily

(Editor's note: This story is part of Taking Care, an ongoing series on the diverse lives of America's family caregivers, with support from The John A. Hartford Foundation.)

June Yasuhara, 55, suffered bouts of severe anxiety all her life. During a major episode, she couldn't even mail a letter.

"You don't feel you are capable of anything," she says.

Worry about her parents' health was always a major trigger. So when both her mother and father developed dementia, Yasuhara's anxiety should have came on hard.

Trauma Undiscussed

Both parents survived World War II. June's mother Eiko Oka, 83, grew up in Japan. Eiko Oka and her sister sheltered in a bathtub from the American firebombings of Tokyo during World War II. Yasuhara's father James Oka, 87, grew up in San Jose, Calif., where the family lives currently. When James was seven in 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which sent his family to a concentration camp in Park County, Wyo., Heart Mountain Relocation Camp.

Heart Mountain was one of 10 concentration camps where Japanese Americans were interned after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

The intense physical labor is easy compared to the emotional cost.

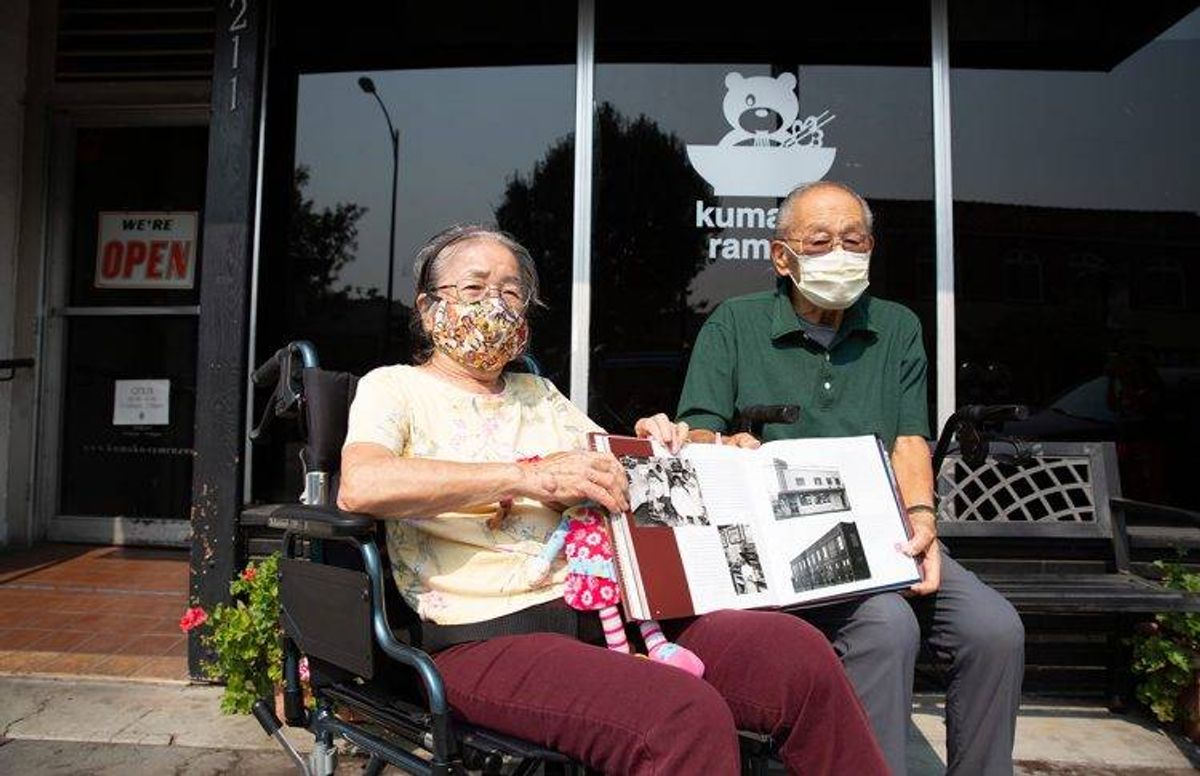

After the war, James returned to San Jose. He worked in the city's Del Monte Cannery. Eiko immigrated to the United States when she was 17. She was working at a coffee shop in San Jose's Japantown when the two fell in love. The couple built a life around their two children and rarely discussed the trauma each had experienced.

"I think it was just part of life," says Yasuhara. "Especially in the Japanese community, you didn't hear a lot of 'That's not fair.'"

The injustice of her father's internment hit June in her 40s, when she helped with a move.

"We were moving out crate boxes that said 'Oka', and we asked 'Where did this come from?'"

The crates stored the Oka family's belongings when the U.S. government confined them. In 2019, Yasuhara and her children made a pilgrimage to Heart Mountain. She found a child's carving of her father's name.

"I took a crayon rubbing of it and brought it back to him. He does still remember writing it," Yasuhara says.

She wants to bring her father to see it, but her parents' dementia and the coronavirus prevent traveling.

Best-Laid Plans

"They're frustrated," says Yasuhara.

Her parents recognize their own dementia, even if they can't name it. Eiko apologizes for being a "baby." James, a former electrical engineer, forgot how to make breakfast.

"My dad, I see him staring at the ground, just puzzled, and he's like, 'I don't know what to do,'" says Yasuhara.

Any transition worsens their symptoms. After one hospitalization, James didn't recognize the family's home.

"When did we move into this house?" he asked.

Last year, James lashed out at Eiko after she blocked the TV. For Eiko's safety, Yasuhara relocated her mother to a nursing home.

"We thought it would be really nice for her. There were people that we knew there, and the manager spoke Japanese," Yasuhara says.

But the move was a disaster. Eiko couldn't sleep in the nursing home and wandered. James was alone, crushed.

"He would write in a journal, 'I wake up and you're not here, I'm all alone," recalls Yasuhara, who now rents an apartment for both parents in San Jose's Japantown.

She arrives at 7:30 p.m. every night and sleeps over, leaving at 2:30 p.m. the next day to spend a few hours with her husband and sons who are 21 and 15. She's lost 28 pounds, but the intense physical labor is easy compared to the emotional cost.

"It's sad to see people that you went to for strength and advice relying on you now just for a daily routine," says Yasuhara.

She gets frustrated when her best plans go wrong.

Yasuhara set up a smart display — a device that combines a voice-activated smart speaker, a touch screen video chat device and a home security screen. "If you call, your face just comes up, and you can talk. They don't have to push any buttons. But what does he do? He unplugs it because he thinks it's like a TV," she says.

Yasuhara's Care Strategies

Her sister has eight young children, so she can't always help. Acquaintances imply her sister should do more.

"They tried to get me mad at her, but getting mad at her does not help," says Yasuhara. "I now avoid those people."

Eiko speaks little these days, so Yasuhara has strategies to encourage words.

"I wear shirts with cute little things on it. Cute Japanese sayings, because she loves to read. We sing together. She was an opera singer back in Japan," notes Yasuhara.

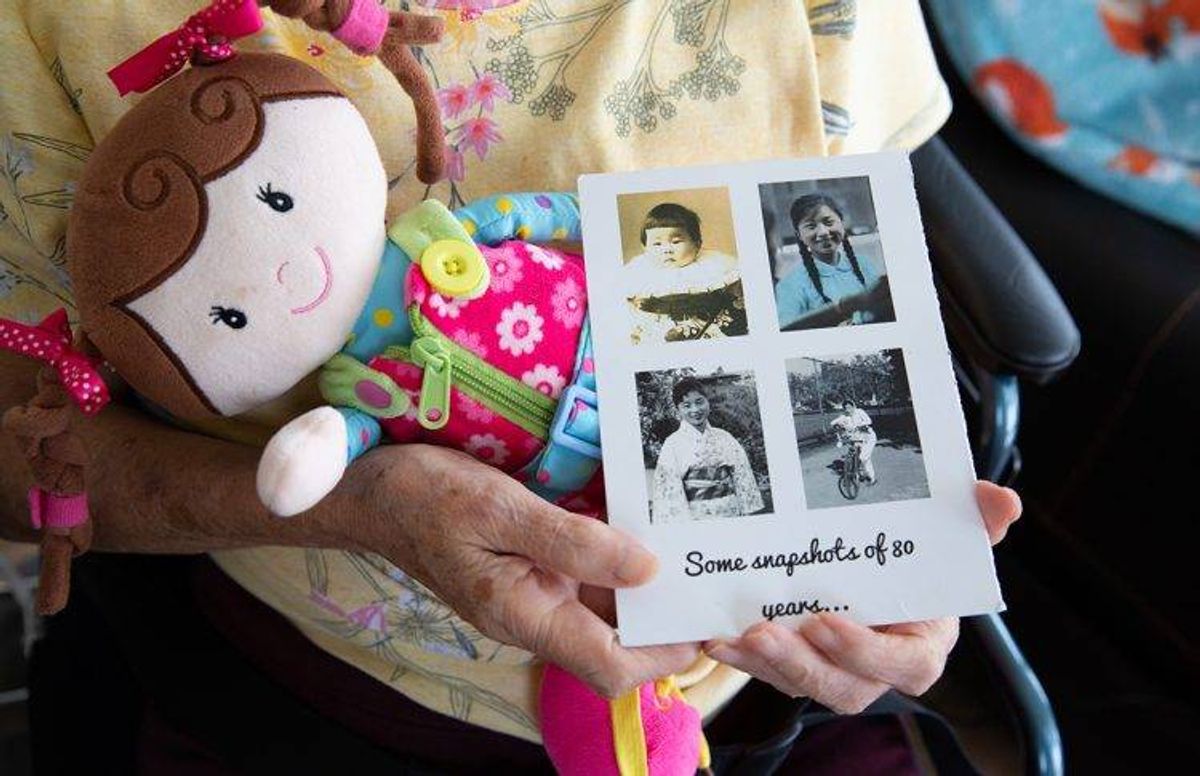

Other activities encourage manual dexterity. Yasuhara grew up with a Dressy Bessy doll, and she bought a similar doll for Eiko.

"It encourages you to button, and it has snaps and zippers. She kisses it," says Yasuhara. "I asked her, 'What's your new doll's name?' and she said 'June.' For her to name something precious to her with my name, yeah, it was very heartwarming."

Yasuhara thinks the routines she had already established with her parents before the pandemic made COVID-19 manageable.

"It's gotten me into a schedule for myself. I feel like things were put into place better," says Yasuhara.

They receive meals from a local senior center three times a week, and a friend's mom brings homemade Japanese food every Tuesday.

"I've gotten really lucky with the people around me," Yasuhara says.

Because her parents can't visit friends at the senior center anymore, Yasuhara has found other ways to stimulate their brains.

"I try to take them on a walk every day. Every day [my dad] will say, 'Why is everyone wearing a mask?' So I remind him why everyone's wearing a mask. My mom puts it on her eyes," says Yasuhara, who can see the humor in tough situations. She kept a year-round Christmas tree for her mom to decorate, and now that's where they hang their masks.

"My phone ringtone for them is 'Crazy Train' by Ozzy Osbourne, because it just makes me laugh," says Yasuhara.

Dementia in Asian American Communities

Yasuhara's anxiety hasn't come back.

"When the pandemic hit, I was not alone. Without them to take care of, I don't know if I could have survived it, because of my own background of mental illness. I think it's given me something to feel like I'm doing something worthy," she says.

And Yasuhara has coping skills.

"I look back and I think that's why I had that [anxiety]. It made me stronger for right now. This is helping me keep my brain focused elsewhere. I don't have time to worry," she notes.

Yasuhara shares her story to bring awareness to mental health and to encourage caregiving support within her community. "Most of my friends are now taking care of their folks," she says. "It's a lot of work, and we need a lot of support in so many different ways."

Yasuhara thinks dementia remains poorly understood.

"Not a lot of Asians share about it, and that's what I'm trying to figure out," she says. "Is there still a stigma, something you don't talk about, or is it because Asians don't like to bother other people?"

She's participating in CARE, a caregiving research registry for Asian Americans and hopes research will help slow the progression of dementia.

Meanwhile, Yasuhara tries to maintain a healthy outlook, balancing the compassion and humor she learned from her parents.

"If you want to live a good life you just can't resent anything. So that's pretty much what I'm trying to instill in myself," says Yasuhara.

(Correction, Oct. 12, 2020: An earlier version of this article misstated that Eiko Oka survived an atomic bomb. She survived the firebombings of Tokyo.)

Dr. Christine Nguyen is a Stanford trained physician and an award-winning journalist. She writes about caregiving, health, and parenting. She was a Gerontological Society of America Journalists in Aging Fellow. Find her on Twitter and on her website. Read More