Cataract Surgery Showed Me a Clear and Bright World

My life-transforming, curiosity-driven story after undergoing eye surgery

"Why do I look so big?" I asked my surgeon when I went in for a routine checkup the day after my first cataract surgery. That morning I'd woken up and removed the protective shield taped across my face, then put in the first round of eye drops I needed to use four times a day to ward off infection and inflammation.

When I looked in the mirror, I was taken aback. There was a noticeable difference in my size. I seemed to be about one-fifth bigger than I usually appeared. My surgeon smiled at my concern and then explained. Since the surgery, I was no longer looking at myself through my thick prescription glasses but through my newly implanted intraocular lens.

I seemed to be about one-fifth bigger than I usually appeared.

I had needed a correction for near-sightedness or myopia since third grade, and for most of my adult life, my eyes had stabilized with a moderate prescription of -4.5.

Then, over the last two years, as my cataracts grew quickly, my vision declined, first to a correction of -6.75, then -9.25, and then four months before surgery, the optometrist handed me a small sheet of paper marked with -11.25, an Rx categorized as extreme.

Myopia can occur because of too-long eyeballs or problems with the front layer of the eye, the cornea, or the lens itself, the clear inner part. As a result, the light entering the eye falls short of the retina, the part that helps us see images.

My prescription lenses were concave, thin in the center with a widening thickness at the edge, a minus number design that allowed the light rays to diverge and focus a little further back, allowing me to see clearly.

But with the glasses perched on my nose and positioned at a distance from my eyes, my view of the world was smaller, a minification that does not occur with an intraocular lens implanted in the exact location of the natural lens or with contacts that sit directly on the cornea.

A Safe and Common Procedure

I had left behind my contacts -- and my vanity -- at age forty, returning to glasses primarily for comfort and because the availability of designer options made wearing them palatable. But I hadn't realized that for the last twenty-five-plus years, I had internalized a vision of myself and the world that was reduced in size.

Today, more than half of all Americans aged 80 or older either have cataracts or have had surgery to remove them.

Cataract surgery is one of the safest and most common surgical procedures, with a success rate of 99%. Today, more than half of all Americans aged 80 or older either have cataracts or have had surgery to remove them.

The operation takes approximately twenty-five to thirty minutes, with an hour or two of prep time on the front end. It all seemed quite simple when I was told about the process. First, remove my cloudy lenses and replace them with new clear lenses that allow me to see them again.

Still, the idea of someone cutting into my eyes made me quite nervous, and when I started to read more closely about the process and its complexity, I was overwhelmed. So I chose my surgeon carefully and read only what I needed to know to make the necessary decisions and just enough to have a minimum understanding of the difficulties or problems that could occur.

Primarily, I relied on the information I gathered from friends and acquaintances, who told me I would love the surgery, that I might not have to use my glasses as much, and that colors would be brighter. And that all proved to be true.

The plan was to start with my right eye as my vision on that side was worse, and the operation on my left eye was scheduled for two weeks later. However, I am an avid swimmer and yoga practitioner, so I wasn't happy to learn that after each surgery, I would have to limit my activity to leisurely walks around the neighborhood.

Even months later, I wake up and am still in wonderland.

I also had to plan for a lengthy investment of time, as there were multiple trips back and forth to the doctor for pre-op and post-op appointments.

All my trepidation disappeared, however, after my first treatment at the beginning of October, as I could immediately see better and was delighted with the world's startling clarity.

Then, once both eyes had new lenses and my stereoscopic vision was back, I couldn't stop talking about what I saw on my neighborhood walks. I was amazed at the variegated textures of the plants! I was thrilled by the changing leaves! I was stunned by the pistachio tree down the street that was turning bright orange!

I posted photographs on Facebook representing my pre-surgical and post-surgical vision and sent emails to family and friends with an overabundance of exclamation points!!! "I loved your message," one wrote back. "I can feel how happy you are." And my son texted in response to my exuberant descriptions, "sounds almost magical."

A Feeling of Strength

But, I was still surprised when I looked in the mirror, and in the days and weeks that followed, this larger image seemed to prompt a subtle and profound shift in self-concept. I felt differently embodied and stronger.

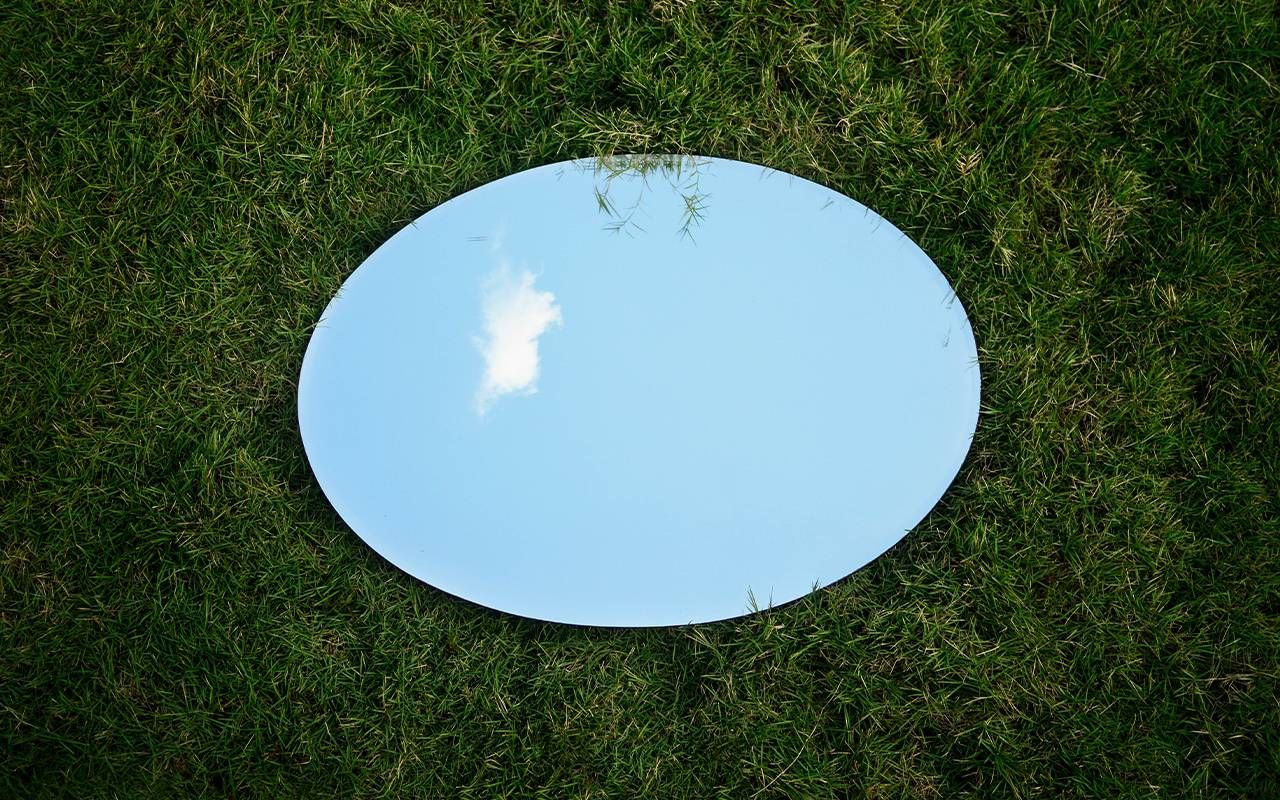

My world was larger, and I experienced more certainty in my perceptions. With my surgery complete, I was no longer anxious. Instead, I was growing "curiouser and curiouser," a phrase borrowed from the adventurous Alice in Wonderland, who also experienced a confounding change in size. I began to read more intently to bring into focus the details my initial fear had prevented me from understanding.

In a young and healthy eye, the crystalline lens is an elastic disc with musculature that allows it to change shape quickly as we shift our gaze from a distant scene to something up close, such as our phone or a menu.

Yet, such an elasticity decreases as we age, and by our late 30s or early 40s, most people's ability to see things in close range is beginning to fail. This presbyopia condition is quickly addressed with reading glasses, bifocals, and progressives for those already wearing corrective lenses.

We are dealing with a living organ, and each individual has a unique way of healing.

Cataracts are also a normal part of the aging process and begin to form when the proteins in the lenses start to break down, clump together and create a cloudy area that makes vision blurry and hazy.

Cataract surgery dates from as early as the 5th century BC when a rudimentary process called 'couching' used a needle to push the cataract out of the visual axis. The French surgeon Jacques Daviel is said to have conducted the first extraction in 1747. Two hundred years later, in 1949, the British ophthalmologist Sir Harold Ridley implanted the first intraocular lens.

This innovation was prompted by his observation that wounded World War II pilots could tolerate the plastic shards lodged in their eyes. Since that time, there have been remarkable advancements in surgical technique and lens replacement technology, and today's procedures are often described as cataract refractive surgery.

Instead of just restoring a patient's lost vision, removing a cloudy lens is considered an opportunity to provide a vastly improved ability to see depending on that person's particular eye anatomy, health and lifestyle.

How I've Adapted to My New Vision

This usually involves the implantation of what is currently called premium lenses and the use of laser, all considered electives that come with associated out-of-pocket costs.

Promotions for refractive cataract surgery often claim that clients will "go spectacle-free" or can "get [their] youthful vision back." But as my surgeon explained, there is always variability in the process. "It's a biological system," he said to help me understand.

So in the research I did after my surgery, I duly noted that every scholarly article I read included some variation of the following phrase: Despite impeccable surgery, there is always unpredictability because we are dealing with a living organ, and each individual has a unique way of healing.

My vision was good even in the first few days, and today I need corrections for crisper night vision and extended close-up work on the computer.

That near-perfect success rate associated with cataract surgery refers only to the extraction of the cloudy lens and an overall improvement in vision. Therefore, it differs from the rate at which any surgeon can meet a targeted vision goal.

After carefully studying the IOL lenses on the American Academy of Ophthalmology, I chose an Extended Depth of Field lens or EDOF. This allowed me to avoid the visual artifacts of halos and glare often associated with multifocal lenses but still have reasonable distance and intermediate vision with some ability to see close-up.

My surgery also included using a laser for part of the process. It is considered more precise and has the added benefit of quieting my squeamishness about a manual incision in my eye.

Like other premium lenses, the EDOF does not mimic a natural biological lens's accommodating and shifting function but instead uses sophisticated optics to create additional avenues for sight. Ophthalmologists use the word neuroadaptation to describe this post-surgery process that can occur as the brain and eyes learn to work together and develop new neurocircuitry to deal with visual challenges.

My surgeon had cautioned there might be some period of adjustment. I did not have this issue. My vision was good even in the first few days, and today I need corrections for crisper night vision and extended close-up work on the computer.

But I have had to adapt – not by seeing differently but by being different. This has been both a bit disorienting and, at the same time, pleasurable. My increased visual acuity has compelled me to reconcile with a seemingly more substantive persona, bringing a clear, bright and larger world into focus.

Yet, even months later, I wake up and am still in wonderland.

Read More