Challenging Conversations Call for Creative Approaches

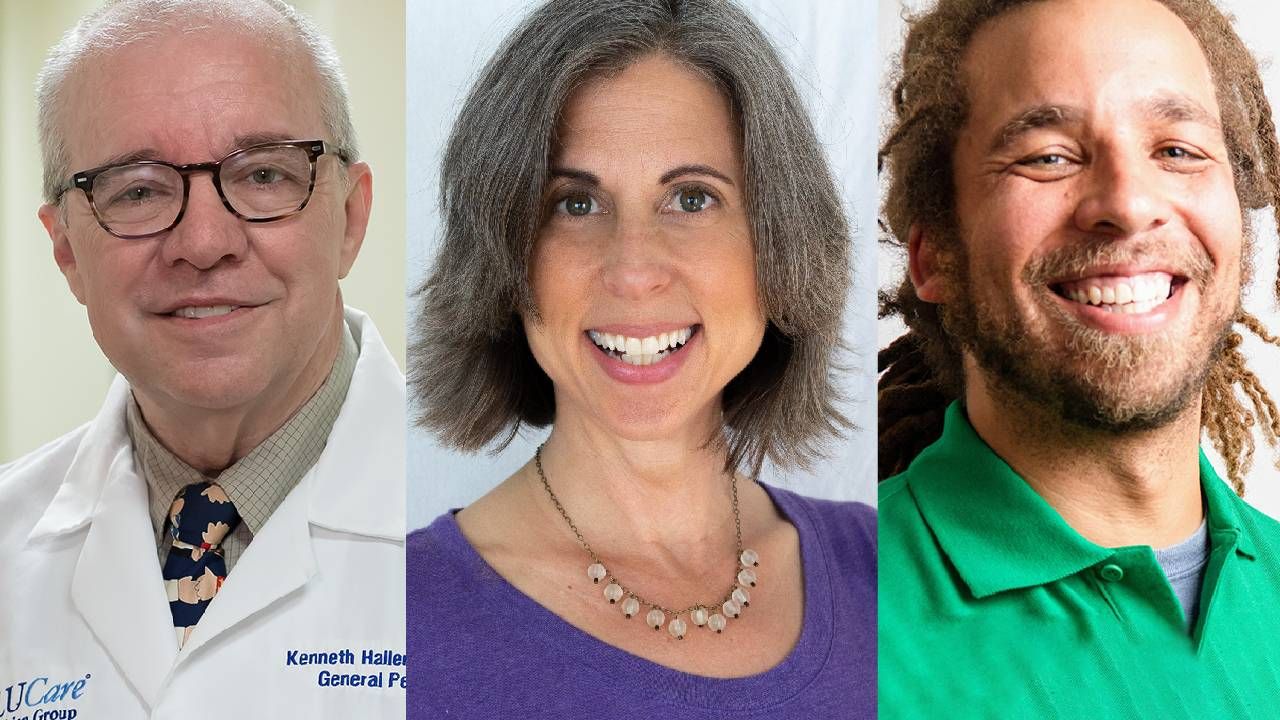

Tips on moving tricky conversations forward from a community organizer, a pediatrician and an intimacy coordinator

"If you don't like what's being said, change the conversation," ad man Don Draper counseled a client on TV's "Mad Men."

A community organizer, an intimacy coordinator and a pediatrician know firsthand how reframing an issue can lead to positive changes, even when that issue may be challenging. Each has ways to move important conversations forward and, below, offers tips on how we can do that, too.

Find Areas of Agreement

Gerald Smith, a high school math teacher, works with people across the political spectrum to help re-energize Indiana, Pa., a city of about 13,000 that's about 60 miles east of Pittsburgh. Smith, 46, moved there from Seattle in 2010, when his wife, anthropologist Amanda Poole, accepted a teaching job at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Soon enough, Smith realized the community-organizing skills he'd honed on the west coast would be of use.

"I've taken a lot of heat for my politics, but I continue to look for common ground."

"We considered Indiana a fantastic place to raise our kids, but just a year or so after we got here, there was a campaign to close the elementary schools because of the declining population," Smith said. "That was a big deal to us." He started going door to door, talking with his neighbors.

"Indiana is a really conservative town. But this was not so much political as it was about families, an issue with a clear common interest, one of shared values," he said. Over time, residents changed the membership on the school board and saved the schools.

Smith was then asked to run for the Indiana Borough Council. He has served for eight years and is now its vice president. While in office, Smith has led the Public Works Committee and helped found the Indiana County Sustainable Economy Task Force, which is crafting a resiliency plan to help the community build back from an economy based on fossil fuels.

He has worked with community groups on bicycle and pedestrian projects, led film festivals and local news programs and helped raised funds to expand low-income residents' access to the farmers market. Police reform, civil rights and racial justice also are causes Smith embraces.

"I've taken a lot of heat for my politics. But I continue to look for common ground, focusing on one galvanizing question: What else can Indiana be?" he said. "We have to work together to make Indiana more welcoming to everybody. To do that, we have to find areas of agreement and build on those. Too many people think there aren't any — but I know that's wrong."

Speak Up for Yourself

An intimacy coordinator for movies and TV shows in Los Angeles, Jean Franzblau is present on the set to support actors performing romantic or otherwise emotionally charged scenes.

"I'm like a stunt coordinator, on hand when a scene may make actors feel vulnerable or emotionally exposed," she said. "I open up the tricky conversations where art intersects with commerce, physical boundaries and a performer's well-being. I help the production avoid a range of problems, from accidental harm to predatory behavior, and I help cast and crew members have better experiences on the job."

Franzblau, 51, received her coordinator certification in 2019. The job was "a perfect fit," she said, with her extensive corporate communication skills and her work as a sex educator.

In her job, Franzblau first reads the script and talks with the creative team about their vision for intimate scenes. Then she speaks with the actors to discuss any contractual or personal boundaries. If needed, she speaks again with the creative team about anything that may need to be adjusted.

"On one set, I worked with an actor just under eighteen who was anxious about a kissing scene," Franzblau said. "On another, I suggested an actor in a nude scene would be more comfortable in shorts and a tube top for close-up shots of the face. One time, I helped an actor who wanted limited nudity during a scene navigate that discussion with the production team. I'm there to protect the actors, and my presence tends to keep people on their best behavior."

"People often make decisions based on emotions, and I have found that acknowledging and affirming those emotions is important."

Before intimacy coordinators were on sets, script supervisors or costumers sometimes tried to run interference for actors concerned about intimate scenes.

"That put them in an awkward situation, one they weren't trained to handle," Franzblau said. "Sometimes, of course, directors handled everything beautifully. But in other instances, actors' concerns were not heard and they ended up feeling uncomfortable or even assaulted and traumatized."

Franzblau hopes audiences who appreciate intimate scenes on TV and in movies understand that they can be awkward and even difficult to create, and that some actors may even dread shooting them. "There is an art to it," she said.

She added: "We all deserve body autonomy. Any time your body says 'no' to an offer of touch, speak up for yourself."

Meet People Where They Are

For decades, Dr. Ken Haller, a pediatrician, has used his improvisational theater skills to discuss parents' fears about vaccinations for their children. Now, when parents tell him they are hesitant about getting the COVID-19 vaccine for themselves or their older children, he employs the "yes…and" improv rule, agreeing with what has been said and then moving the conversation forward.

"I acknowledge that scary information is out there, and I say I can see how much they love their children and want to protect them," said Haller, 66. "Then I encourage them to talk with me about their specific concerns, to see what I can add."

A professor of pediatrics at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine and SSM Cardinal Glennon Children's Medical Center in St. Louis, Haller noted that though these conversations are time-intensive, "it's worth it."

Doctors and scientists typically believe that evidence by itself is convincing, but that's frequently not enough for many others. "People often make decisions based on emotions, and I have found that acknowledging and affirming those emotions is important," Haller said. He wrote a post on this, called "Getting to Yes," on Medium.

"If I say to a parent that I see your fear and your love and they are valid, that parent feels seen and heard," said Haller. He teaches the technique to first-year medical students in his class "Acting Like a Doctor."

Haller cited a second source who recommends a similar approach. "Carl Rogers, a pioneering psychologist, wrote in the 1950s about client-centered therapy, noting that it's important for health care providers to find something to like or love about every patient. I've been doing that for years, too," he said.

Do these techniques work? About half the parents Haller talks to get vaccinated, Haller noted.

He added that when someone says they don't want the shot because it's going to do harm, his initial reaction often is an emotional one.

"Right away, I wonder if the person thinks I'm stupid or evil," Haller said. "I have to remember that it's not about me, so I can move past that response and engage my rational brain. Only then can I truly meet people where they are."