There's a Target on Charity's Booming Donor-Advised Funds

Critics say they're a goody for the wealthy and not helping active charities enough

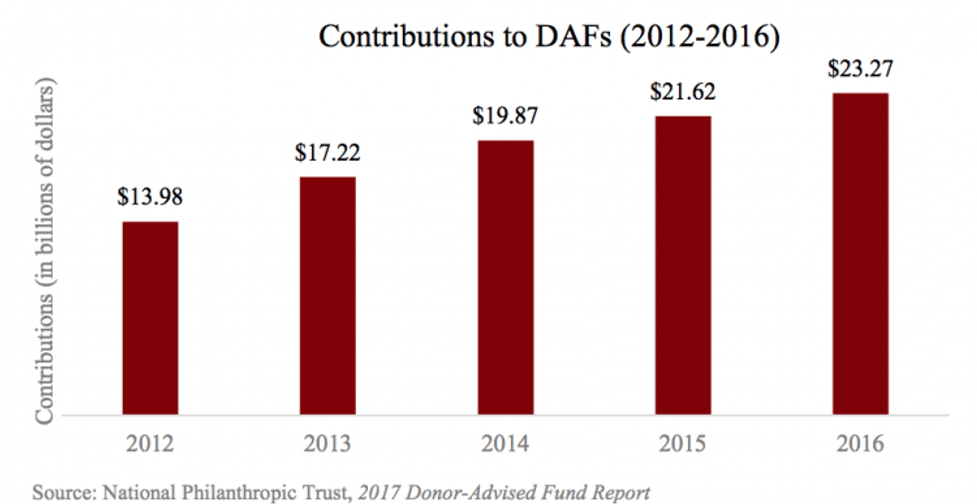

What do you think is the nation’s biggest charity? The United Way? The American Cancer Society? The Salvation Army? Nope. It’s something called Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund, which is also the largest donor-advised fund in the United States. The rocket-like growth of this and other donor-advised funds with total donations of $23 billion in 2016 — an increasingly popular way to donate to charity and get substantial tax breaks — is exactly why the vehicle now has a giant bulls-eye on it.

The title of a new, scathing report by the liberal Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) attacking donor-advised funds, Warehousing Wealth: Donor-Advised Charity Funds Sequestering Billions in the Face of Growing Inequality, says it all. “A fair amount of the funds could be deployed in a more timely way,” one of the study’s co-authors, Chuck Collins, told me. “There’s a wiring problem that should be corrected.”

Donor-Advised Funds: 'The Thing That Ate Philanthropy'

And if you’ve sent cash or appreciated shares of stock to mega donor-advised fund national sponsoring organizations like Fidelity Charitable, Schwab Charitable — the nation’s sixth biggest charity — or Vanguard Charitable, you’ll want to keep an eye on Washington, D.C. to see if the rules change. They just might. (There are two other types of donor-advised fund sponsors: single-issue charities like The Sierra Club Foundation and community foundations.)

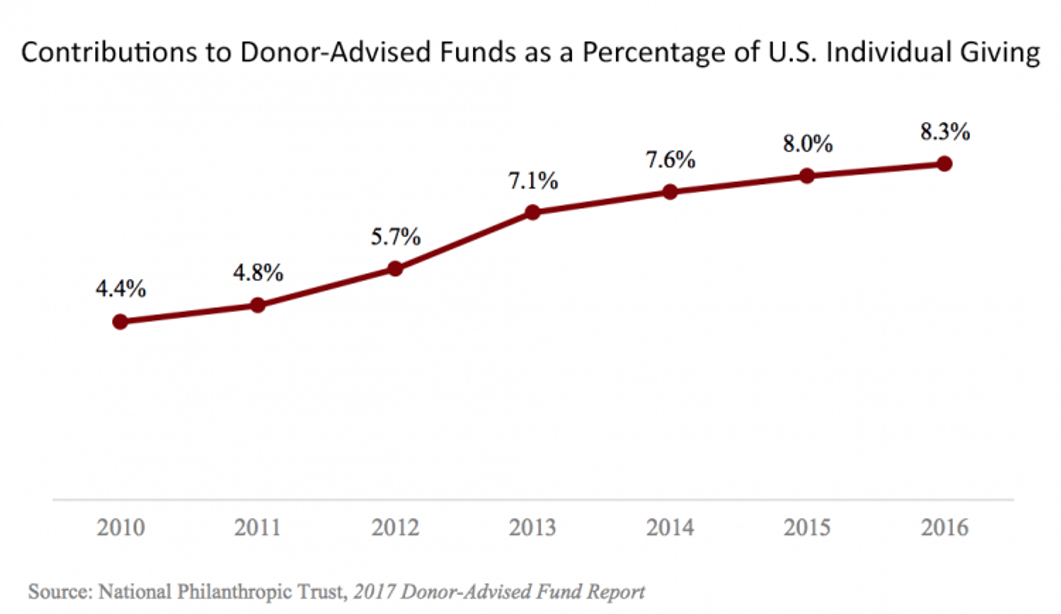

Though donor-advised funds have been around since the 1930s, lately they’ve become such a huge part of the charity world, they’ve been called “the thing that ate philanthropy” and “the most noteworthy story affecting charity in 25 years.” From 2012 to 2016, according to the IPS report, giving to donor-advised funds grew more than four times faster than individual giving in the United States as a whole, comprising 8.3 percent of individual giving in 2016.

How a Donor-Advised Fund Works

Think of a donor-advised fund (DAF) account as kind of a tax-advantaged charity brokerage account. The sponsoring organization is a charity that holds and manages donors’ contributions — cash, stocks, bonds, real estate, even business ownership — for the purpose of making grants to other charities, once (or if) the donors tell them to do so. Opening one is less expensive and requires less administrative overhead than establishing a private foundation, the IPS report noted. Annual fees include an administrative fee of roughly 0.6 percent of assets plus an investment fee whose size depends on the funds the money is put in. Donor-advised fund money grows tax-free in the sponsoring organization’s DAF investment funds until it goes to the donor’s chosen charities.

When you give the donor-advised fund your money, you can immediately claim a tax-deductible charitable contribution (if your deductions exceed the standard deduction; $12,000 for individuals and $24,000 for couples filing jointly in 2018), even if you haven’t directed the sum to what are called "active" or "working" charities — the kinds that do things to benefit the public good.

And if you give a donor-advised fund appreciated stock or another investment that turned a profit for you, its capital gains will escape taxation. (Donor-advised funds are especially popular in Silicon Valley because so many tech founders and employees have seen the value of their company stock balloon, with accompanying capital gains.) Because last year’s tax law doubled the standard deduction starting in 2018, some investors poured money into donor-advised funds in late 2017 to claim the write-off while they could.

The Fidelity and Schwab Donor-Advised Funds

Donor-advised funds like Fidelity’s and Schwab’s only require a $5,000 minimum, which is why those companies refer to DAFs as “democratized giving.” Schwab Charitable and Fidelity Charitable told me their donors give more to charity than they otherwise would because of their donor-advised fund accounts. Fidelity has 180,000 DAF donors and made a record 1 million grants to over 127,000 charities, totaling $4.5 billion in 2017. Schwab Charitable donors have supported over 130,000 charities with grants totaling more than $10 billion.

Schwab Charitable said in an email that it was established “at the request of our clients to make it simpler and easier for them to plan and increase their charitable giving” and does so “by providing an efficient and low cost platform to contribute appreciated investments and non-cash assets” and “by offering a broad range of investment options that allows clients to grow their assets over time and give even more to their favorite charities.” And Fidelity Investments Senior Vice President Vincent G. Loporchio emailed: “We are helping donors who otherwise would not have a good alternative for planning and maximizing their giving.”

So what’s the problem?

What Concerns Critics About Donor-Advised Funds

There are quite a few problems, say critics who’ve dubbed donor-advised funds “waiting rooms for charitable donations” and “charity checking accounts.” They point to the following:

The donor doesn’t have to ever instruct the donor-advised fund to move the money to a charity. As Rick Kahler, founder of Kahler Financial Group in Rapid City, S.D., told Forbes’ Larry Light recently: “A DAF allows you to make a large, tax-deductible gift in one year, but decide in the future — a day, 10 years or 100 years later — when and how to distribute that gift.” Some donors intentionally don’t name charities quickly, preferring to use the DAF as a legacy tool, letting their children or grandchildren decide one day where to send the money.

University of California, San Diego, economics professor James Andreoni, recently wrote that if people claim tax breaks for steering money to donor-advised funds but don’t send the money to active charities, “they may create no benefits for society, but add significantly to the tax costs to the U.S. Treasury.”

The giant donor advised funds told me that most of their contributions do ultimately get distributed to charities. Schwab Charitable said 80 percent of its contributions have been fully distributed to charity within 10 years. Fidelity said 74 percent of its contributions are distributed to charities within five years; 84 percent within 10 years. Of course that means 16 to 20 percent of their contributions aren't getting to charities within 10 years.

To its credit, Fidelity nudges donors to make charity grant recommendations if they haven’t done so within three years of giving its DAF money; after that, if the donor doesn’t name charities, Fidelity Charitable will start choosing them. And after seven years, Fidelity will grant the entire balance to one or more charities approved by Fidelity Charitable trustees. “That’s a good start,” said IPS’ Collins.

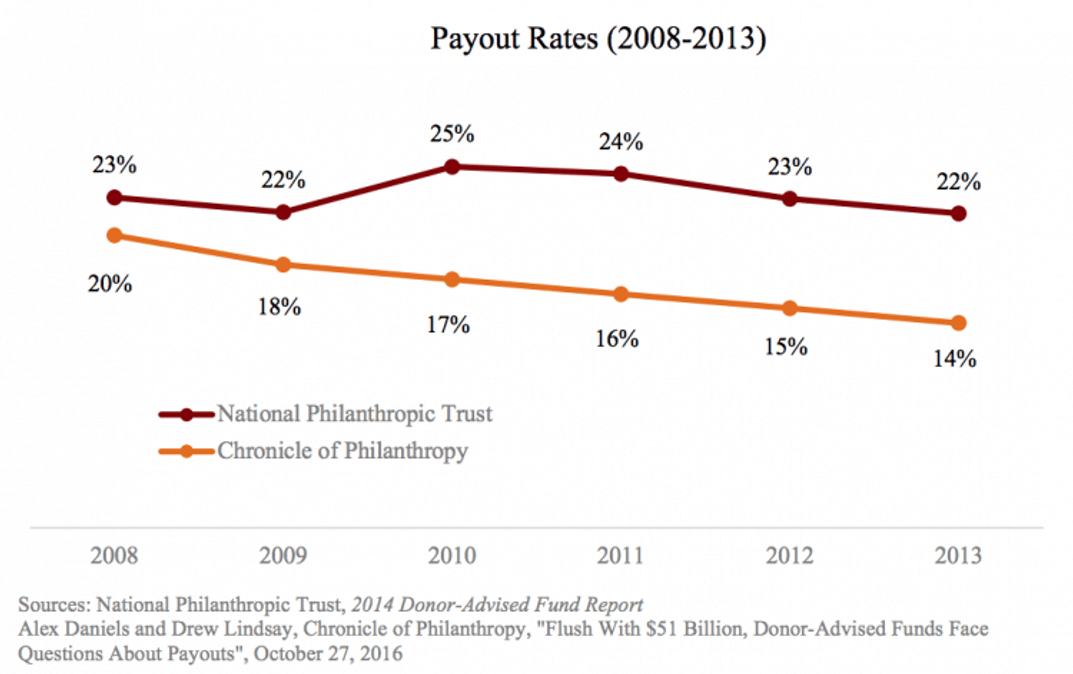

Donor-advised funds’ payout rates to charities are low and getting lower. The payout rate is the result of dividing the dollars paid out in charity grants in one year by the total value of the assets in the donor-advised fund. As you can see by the chart below, payout rates overall have been declining since 2010 — not because the funds are doling out fewer dollars, but because the assets in the accounts have been growing faster (up 90 percent from 2012 to 2016 according to the Institute for Policy Studies report).

Fidelity told me its payout rate is 24 percent. Schwab Charitable said “annual payout rates for national DAF providers and for Schwab Charitable average about 20 percent of assets, which is 4-5 times that of private foundations.” Collins’ response: “Their payout should be 100 percent! They’re an intermediary. The whole purpose of donor-advised funds is to move money to working charities.”

Donor-advised funds often most benefit America’s wealthiest, partly because they appeal to investors with capital gains; most low- and middle-income people lack such assets. According to Andreoni, the average DAF donor is a member of the wealthiest one tenth of one percent of Americans, with annual income over $1 million.

That may be true overall, but Fidelity told me that 60 percent of its DAF accounts have balances of $25,000 or less and its median account balance is $18,000. Schwab Charitable’s told me its donor base “is very diverse, with account sizes ranging from $5,000 to hundreds of millions. Roughly one third of Schwab Charitable accounts have balances of $10,000 or less.”

Collins said he’s glad some smaller donors use donor-advised funds, but “the vast volumes” are from high-net-worth investors, particularly non-cash donations such as appreciated stock.

There’s a built-in incentive for financial firms with donor-advised funds to keep the money rather than distribute it to active charities. Fidelity and Schwab donor-advised funds carry management fees based on the amount of assets in them; the larger the assets, the more money the companies earn in management fees. And the IPS report said Fidelity advisers whose clients set up a donor-advised fund at Fidelity Charitable get a bonus for that.

Schwab Charitable told me that the amount of support Charles Schwab & Co. provides to its donor-advised fund is “far greater than any fees it receives for investment management.”

Proposed Reforms for Donor-Advised Funds

The Institute for Policy Studies and other analysts offer proposals such as the following to reform donor-advised funds:

- Require distribution of donor-advised fund donations within a fixed number of years. Some suggest a maximum donation payout period of three, 10 or 15 years. In 2014, the Republican House Ways & Means Chairman, David Camp, proposed a five-year maximum distribution, with remaining assets after that subject to a 20 percent excise tax.

- Delay the tax deduction to donors until after the funds are paid out to active charities. This is essentially the opposite of the previous proposal.

- Change the way management fees are determined so they no longer increase as result of the size of the donor-advised fund’s assets. For example, there could be a flat, or a capped, fee.

As you might imagine, financial firms sponsoring donor-advised funds and the Council on Foundations, the foundations' national trade group, see no need for reforms. “We disagree with the [Institute for Policy Studies] report’s findings,” said Fidelity’s Loporchio.

The Council on Foundations site doesn't mention the IPS report specifically, but says: “The Council strongly opposes any proposals that require a DAF to pay out a percentage of funds each year, or to exhaust funds within a specified period of time. Such proposals are misguided as to the realities of donor-advised funds, and would be more harmful than helpful to supporting charitable causes in communities across the country.”

Collins, of IPS, told me: “The independent sector… doesn’t want to alienate donors” and that "financial services firms are a powerful lobby opposing ideas to change donor-advised fund rules.” But, he added, “to fundamentally rewire donor-advised fund incentives, we need an act of Congress to redefine what is allowed.”

He believes “there’s enough push now for some regulatory action.”