Innovative Communities Expand and Redefine the Dementia Experience

The movement that's changing dementia culture from stigma to inclusion

Ron Grant of Oklahoma City was 55, enjoying his career as a chaplain and happily married when he began to experience memory problems.

After undergoing a battery of tests, he received an unexpected diagnosis: early onset Alzheimer's disease, a type of dementia. "Nobody in my family had it," he says. "I knew it was a bad disease, but I did not know anything about the progression."

When he pressed his doctor about what to expect, Grant was told he'd likely be dead or in a nursing home within two to seven years.

That was 14 years ago. Today, Grant continues to live fully. As co-chair of Dementia Friendly America, an initiative that began during the White House Conference on Aging in 2015, he is a leader in the movement to change societal views of what it means to live with dementia.

"We do not lose our humanity and our right to dignity just because we have this disease," Grant says.

"We need to listen to [people living with dementia] and we need to talk to the folks who are shy and hesitant to find out what they want in their communities."

The Dementia Friendly America network promotes localities, organizations and individuals who are committed to keeping people with dementia and their care partners engaged and thriving in their communities.

Too often, though, the "tragedy narrative" prevails, says gerontologist Karen Love, executive director of the nonprofit Dementia Action Alliance. Instead, communities can seek "to empower people from the get-go and fill them with a sense of positivity," she says.

Anecdotally, Love has found that engagement and hope may help extend the time of cognitive health.

Grant agrees. He continues to have purpose and meaning, crediting his faith and the changes he and his wife, Vicky, made early on with taking him as far as he's gone.

"We learned that our worst enemy is stress, fear and anxiety," he says. "We purposefully tried to de-stress, to try to overcome fear and avoid all anxiety that we could."

He also found help in a support group he organized. Support groups, often led by those who have the disease, are among many activities cropping up around the country to improve the quality of life for people with dementia.

Memory cafes that offer the chance to socialize and build new networks, volunteer opportunities for those with dementia, concerts and special art gallery tours are spreading. There is even the nation's first dementia-friendly airport in Tulsa, Okla.

Dementia Friendly America has registered 350 communities so far. That number does not include several other dementia-inclusive communities that aren't under the organization's umbrella.

"This is a movement that's gaining momentum," says Sandy Markwood, CEO of the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging.

That momentum has continued during the pandemic. Over the last year, 25 more communities joined, pledging to include in leadership people who have dementia and to work across sectors (including local government, business and faith- and community-based organizations) to implement dementia-friendly practices. Dementia Friendly America developed a toolkit to guide communities that wish to become dementia-friendly.

The organization is now working with partners to develop an evaluation tool to measure if and how such practices improve the lives of people with dementia, their families and their communities. The tool will be piloted later this year.

"The key is being dementia-inclusive," says psychology professor Susan McFadden, author of the new book "Dementia Friendly Communities: Why We Need Them and How We Can Create Them." She adds: "We need to listen to [people living with dementia] and we need to talk to the folks who are shy and hesitant to find out what they want in their communities."

Below are a few examples:

Dementia-Friendly Indiana

A standout in this effort, according to Love, is Dementia Friendly Bloomington (Indiana). Its first workshop was in 2017 to brainstorm what a dementia-friendly community would look like. Today, committees work on expanding legal and financial services, safe driving and making public spaces dementia-inclusive. This initiative offers employee training to businesses and, with the guidance of people with dementia, suggests ways to make places more navigable and safer.

"My philosophy is that people living with dementia need a friend to help them walk through life," says Jan Bays, who helped found DF Bloomington. "They have many, many abilities, and they see the world differently because their brains process things differently. The key to living successfully is having a safe environment that supports them."

Among Dementia-Friendly Bloomington's many activities: The Sing for Joy! choir for older adults includes those with dementia.

"They do very sophisticated music," says Bays. "We have the music and the pacing done for people living with dementia. We do dementia-friendly training for all choir members, and then we put on programs four to six times a year."

In collaboration with a theater group, people with dementia have also acted in plays over Zoom. "It might be hard for them to remember lines, so they can have their scripts," explains Dayna Thompson, who heads up the Alzheimer's and Dementia Resource Service at Indiana University Health. "They are over the moon to be included in this," she says.

"Our elevator pitch is the dementia journey can be overwhelming, but no one has to walk it alone."

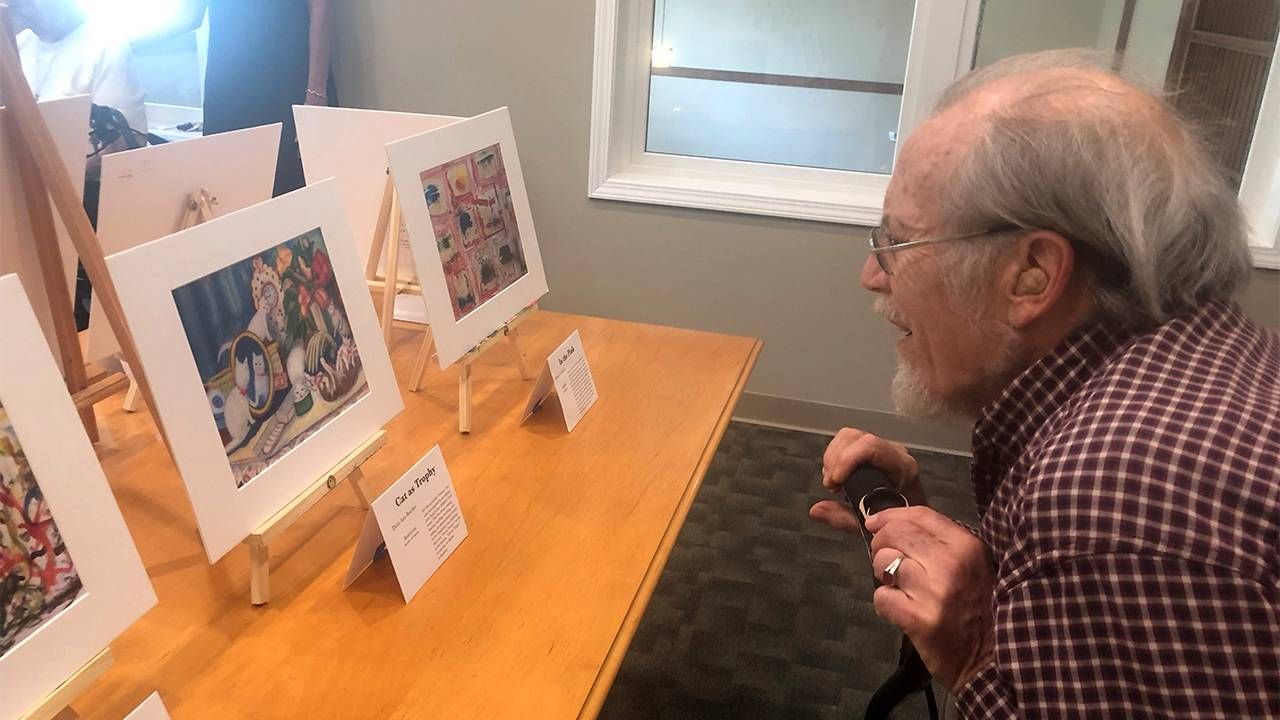

Thompson's team also partnered with the Monroe County History Center and the Community Foundation to create Living with History. The History Center reserves times for people living with dementia. In a quieter environment, they can go on Memory Walks, hang out at a Memory Cafe or borrow Memory Boxes to take home.

Dementia-Friendly Bloomington has now spread to 12 counties and plans a statewide conference this year.

"I truly believe that if we're focusing on people living with dementia in our community, it will make life better for all of us — giving information, safely finding transportation in town, improving way finding, checking on our neighbors, having places where people can socially engage across generations," says Thompson. "We might call it dementia friendly, but it's what we all would like."

Dementia Friendly Nevada

Jennifer Carson, a dementia researcher at University of Nevada, Reno, hoped to expand programs for people living with dementia beyond the usual orbit of aging services professionals.

"We want to transform the broader community, so how do we find those pathways to change?" she says. "We set as a standard to have diverse representation" across many sectors and to include people with dementia in leadership.

Today, six communities — each representing a range of sectors — are active in Dementia Friendly Nevada. For example, Dementia Friendly Pahrump, on the edge of Death Valley, hosted a film series, complete with popcorn and post-film discussion. With no theater in town, it first used the local electric company to show "Cracked: New Light on Dementia," a research-based drama that seeks to change the stigma around dementia and to promote inclusion.

Dementia Friendly Pyramid Lake Tribe-Pesa Sooname (interestingly, there is no word for dementia in the tribe's language) focused initially on education. The group then organized a summit in 2019 which drew 114 people from 14 tribes.

"The whole summit was developed by our partners," says Carson. "There was a color guard from the tribe, traditional songs and a heart-healthy lunch prepared by tribal members."

One of the best programs, says Carson, is a support group, Dementia Conversations, now held biweekly over Zoom.

Chuck McClatchey, who has dementia, leads the Monday group. At a recent gathering, made up of people with dementia and family members, one participant asked for advice on how to get her husband (who was not attending) to agree to counseling to help him overcome denial and better accept the disease. Others shared their own positive experiences with counseling, which in turn led to a conversation about how they each dealt with learning their diagnosis and getting to a place of acceptance.

The conversation was sprinkled with humor (one participant with Lewy Body Dementia personified the disease as "that rascal Lewy" who disrupts his thinking) and with deep appreciation for the trust and openness in the group. At a closing sharing, McClatchey said, "What I took away is that it's okay to ask for help. Everyone handles stress and anxiety in different ways. All the stigma can go in the trash where it belongs."

Dementia Together in Northern Colorado

What began as a caregiver support group at Cyndy Luzinski's church in 2014 evolved into the nonprofit Dementia Together, based in Windsor, Colo. Luzinski, an advanced practice nurse, is the full-time executive director, supported by three half-time staffers.

In 2020, nearly 1,800 people went to 80 Memory Cafes (in-person and virtual) in Northern Colorado. "The agenda is joy, reminisce, sing, and play games," Luzinski says. "The main purpose is having fun and for the couples to realize they can still have fun together." More than 500 attended "virtual variety shows" including concerts, gardening and cooking programs.

Luzinski saw the power of connection in 2015 when researchers at Colorado State University launched a collaborative to study how the arts could benefit people with dementia. Through the B Sharp Arts Engagement program, people with dementia and their partners attended concerts of the Fort Collins Symphony and participated in post-concert receptions and in research studies.

The first study found not only improved alertness, mood and engagement among participants, but increases in cognition over nine months of going to concerts. For their part, the caregivers found a sense of community and felt a sense of "normalcy."

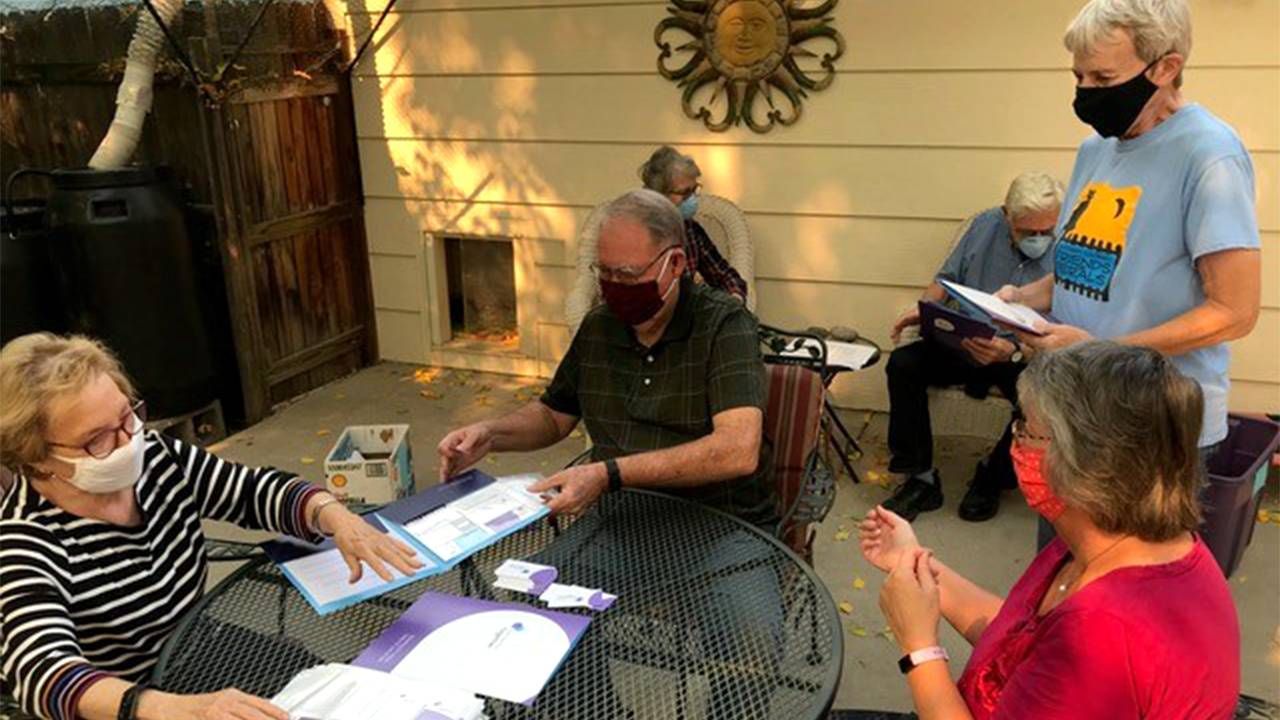

The group also tackled a common problem they heard from newly diagnosed patients. "The doctors would say, 'You have dementia, see you in six months,'" says Luzinski. "That is such a trauma for them." Dementia Together developed a resource folder and distributed it to internists, family practitioners and neurologists to give to their patients. The folder includes basic information about the disease, caregiver tips and helpful local organizations.

"Our elevator pitch," says Luzinski, "is the dementia journey can be overwhelming, but no one has to walk it alone."