How COVID-19 Exacerbated Inequalities in Health Care for the BIPOC Community

The pandemic has devastated communities of color. The reasons why are many, including generations of racist policies.

Parents, siblings, grandparents and children: They are among more than 600,000 Americans killed by COVID-19 since it was first detected in the U.S. nearly two years ago. The coronavirus has been particularly devastating for people 65 and older. They represent a sixth of the population, but are among those hardest hit by the virus and its complications.

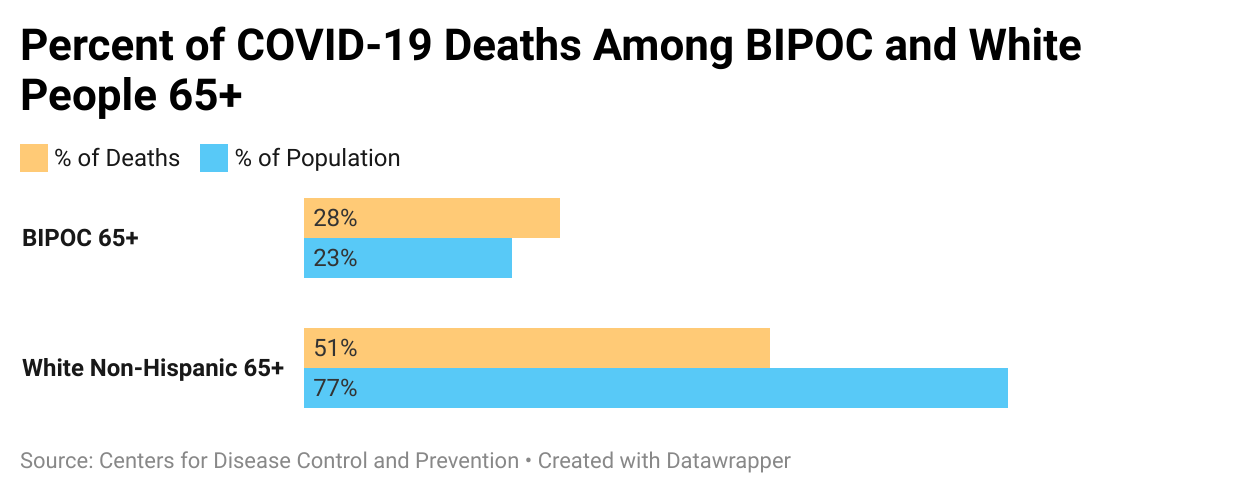

New data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that the virus hits older Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) even harder. The CDC was able to collect race and ethnicity data on 83% of all COVID-related deaths, as of August 25, 2021. Of that, 1 in 4 were 65 and older BIPOC, according to a Next Avenue analysis of the data.

There are many reasons why. In Illinois, for example, some Brown and Black Medicaid customers lived in understaffed nursing home or in nursing homes with four other people in their rooms. This led to an increase in mortality compared to white Medicaid customers.

Others have been affected by structural racism which can contribute to "poorer health outcomes for racial and ethnic minorities and other populations who experience health disparities," according to the National Institutes of Health

But experts and health care officials say one of the biggest reasons is the wealth and income gap. Generations of racist policies have stoked inequality in the BIPOC community and many in it cannot catch up to their white counterparts. The pandemic has intensified these challenges. And for many, overcoming those gaps is now a matter of life or death.

The Cost of Racism

More than one hundred years before the U.S. was founded, African people were enslaved, brought to North America and used for labor. Harvard Kennedy School professor Khalil Muhammad has traced the roots of racial disparity to that colonization period, explaining that European settlers took Indigenous peoples' land and prevented Africans from participating in the economy. When African Americans were freed from slavery, new obstacles shackled them.

Jim Crow laws limited the education, jobs and housing opportunities that the BIPOC community could choose from. Many who opposed those rules would face fines, jail time or violence. The 1965 Voting Rights Act marked an end to most Jim Crow laws, but racism lives on, taking many different forms.

Black students are disciplined at more than twice the rate of white students. Black college students are the most likely to struggle financially from student loan debt. Applicants with "distinctively Black names" receive fewer callbacks for a job interview. And Black people are denied home loans at more than twice the average rate.

When It Comes to Wealth, Little Has Changed

A report by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis found that racial wealth gaps have persisted for 70 years, and white families' wealth now averages at more than $118,000. Black families' average is $13,947.

"This country has racialized poverty," said Denny Chan, directing attorney for the nonprofit Justice in Aging -- a nonprofit advocacy organization fighting poverty among aging adults. "[Class and race] aren't proxies for each other, but they also are so deeply intertwined that you can't talk about one without talking about the other."

According to a May 2021 report by the federal Administration on Aging, Black people who are 65 and older now hold the highest rates of poverty among their peers.

Less generational wealth means fewer dollars to save for retirement or for the costs of prescription drugs and other health care-related needs throughout life. These disparities in health and health care even extend to dementia care and the ability to get a diagnosis, for example.

In March, the Alzheimer's Association released a report detailing how those disparities played out. It found that older Black and Hispanic people are more likely to have Alzheimer's disease or another dementia, and compared to older white people, were more likely to have a missed diagnosis. The survey also found that roughly 50% of Black people who were surveyed have experienced health care discrimination; two-in-five unpaid caregivers said that race made it harder to get excellent care.

"The decades of racism and discrimination and intergenerational poverty — it builds up on one another so that the disparities are particularly massive among Black or Latinx older adults, and other older adults of color, compared to white older adults," Justice In Aging staff attorney Gelila Selassie said. "It really baffles me because this is a generation that fought for civil rights, that lived through Jim Crow, that saw all these racist policies of the sixties, seventies and beyond. So for this to be how they advance in age, how the end of their life is, is really heartbreaking."

"The pandemic really brought it to the forefront, but there's been disparities before this. They just weren't as obvious."

At-home care could improve aging adults' health, but Selassie said that many members of the BIPOC community cannot afford it. A national survey by Genworth supports Selassie, finding that yearly rates for at-home care can cost more than $54,900.

Nursing homes can be safety nets for families who qualify for Medicaid. But as we saw during the pandemic, these types of settings may exacerbate decades of inequality. And without enough savings or long-term care insurance, being able to afford a private room in an assisted living community or other long-term care setting may be out of reach.

An Improved System That Needs Reform

Wendy Cappelletto believes that the health care industry needs to change.

Cappelletto is a member of the National Association of Elder Law Attorneys and works for the Office of the Public Guardian of Cook County in Illinois. She said racial disparities can be found in the quality of care that nursing homes offer, and even in where the facilities are located.

"[Nursing homes] don't pay well. [There are] transportation issues to get to that place. If people don't have cars you're not going to want to take a bus in the middle of the night," Cappelletto said. "The pandemic really brought it to the forefront, but there's been disparities before this. They just weren't as obvious."

And volumes of research show those disparities in long-term care settings have gone on for years.

A Workforce Made Up of Women and People of Color

A report by PHI, an organization working to create quality jobs for the direct care workforce, found that direct care workers' median hourly wage in 2020 is $12.80. That has barely increased in the past decade. Another report by PHI found 48% of all direct care workers are women of color and one out of five live in poverty. This workforce is also more likely to rely on public benefits.

The report concluded by saying "unfortunately, direct care jobs do not provide economic stability to women of color and their families."

Ironically, PHI projects that the long-term care sector will need to fill 6.9 million jobs in the next decade.

But as Cappelletto said, health care disparities were a concern even before the pandemic. A 2005 report cited by the American Bar Association found that BIPOC patients were less likely than white patients to get "appropriate cardiac care, to receive kidney dialysis or transplants." It also found they were less likely to receive the "best treatments" for conditions like stroke or cancer.

Those kinds of barriers and health inequities have led us to where we are today. And the pandemic has exposed all of it for the world to see. But change is starting to happen — at the local level.

Investing In Future Generations, Now

Earlier this year, Boston Medical Center's Dr. Sabrina Assoumou reviewed her hospital's COVID-19 vaccination rates. She nearly jumped for joy.

Assoumou had worked closely with the medical center to reach more people in Massachusetts, where research shows that five communities with the highest COVID-19 infection rates in the state are home to a majority of BIPOC residents.

Assoumou said that many Black Americans are hesitant to trust health care providers. Some may recall stories of the Tuskegee Experiment, in which Black men were knowingly infected with syphilis by the U.S. government.

"COVID was horrible to communities of color, both in the health aspect and financially. And that is because there has not been the kinds of attention and investment in ensuring that these fellow Americans deserve quality of life."

Although penicillin was available at the time, participants were not offered that treatment. As a result of living with untreated syphilis, many lost their vision, experienced neurological damage or died. With that history in mind, Assoumou knew she would have to take a different approach.

Assoumou made televised appeals, acting as a trusted voice who assured people the vaccine is safe and effective. Then, the Boston Medical Center decided to bring the vaccine to the people. The center joined many local senior centers and community organizations in launching pop-up clinics where BIPOC could easily access them.

After the center launched the pop-up clinics earlier this year, Assoumou looked at the data: 40% of the people vaccinated at the medical center were Black. For context: less than a tenth of the state is Black.

"When you bring the vaccine to people and you make it convenient for them, you can see changes," Assoumou said.

Though it's still important to address generations of health inequities, Assoumou said the community outreach is critical. That's because members of the BIPOC community face barriers besides the wealth and income gap which can keep them from receiving quality health care.

"Start with social determinants of health, which describe the milieu of where a person is born, lives and grows up," Assoumou said."[That] impacts the trajectory and impacts [the] access to opportunities, to education — access to wealth."

And all of that, she said, affects one's access to quality health care.

Data on coronavirus rates highlights how those social determinants may be affecting communities of color. Said Assoumou: "It didn't matter where you were in the U.S., but the curves always looked the same: where Black people, Latinx people and Indigenous people were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic."

Research organizations like the National Institute on Aging have recognized the effects social factors can have on communities' health. Those factors have hurt people for generations, but Karyne Jones says that could change.

Jones is president and CEO of the National Caucus & Center on Black Aging, a nonprofit focused on quality of life for aging people of color. It has worked to inform aging Black communities for decades, and now function as a connector to other programs and resources.

Jones said people today have more health information at their fingertips and can benefit more from that knowledge compared to previous generations. But spreading health awareness is just one piece of the puzzle, she said.

It's also important to build a productive and healthy society, but that means getting everyone to invest in it, she noted.

"COVID was horrible to communities of color, both in the health aspect and financially. And that is because there has not been the kinds of attention and investment in ensuring that these fellow Americans deserve quality of life," Jones said. "We can't continue to think that we can keep the system that we have, and still try to get out of this situation where we have an unhealthy society."

Editor’s note: This story is part of The Future of Elder Care, a Next Avenue initiative with support from The John A. Hartford Foundation.