Afro-Latina Author Dahlma Llanos-Figueroa Finds Her Voice

In her novels, she is committed to telling the authentic stories of her ancestors for future generations

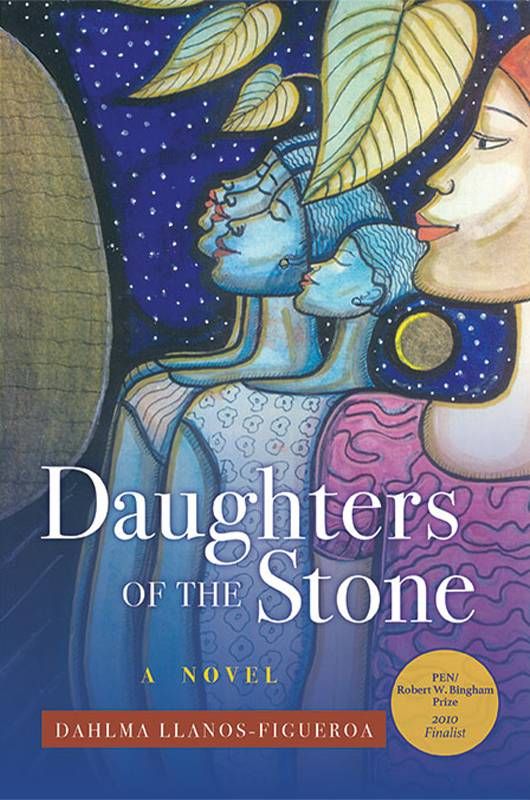

At 72, Afro-Latina author, Dahlma Llanos-Figueroa is living the life she created with intention and purpose. Born in Puerto Rico and raised in the Bronx, Llanos-Figueroa spent 30 years as a New York City middle school English teacher and librarian, but always with an eye on becoming a full-time writer. In 2009, at 59, her first book, "Daughters of the Stone," was published by St. Martin's Press to critical acclaim.

The novel, which tells the story of five generations of Afro-Puerto Rican women from slavery to contemporary times, was a finalist for the prestigious 2010 PEN/Robert W. Bingham Award.

In 2020, the self-published paperback edition won the 16th Annual National Indie Excellence® Award for Multicultural Fiction. Recently, Llanos-Figueroa was named among the 2021 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellows in Fiction.

As she prepares for the release of her second novel, "A Woman of Endurance" in April 2022, the author talks to Next Avenue about how she got started, finding her literary voice and honoring our elders:

Next Avenue: When did you develop an interest in storytelling?

Dahlma Llanos-Figueroa: When I was a child, I was sent to live with my grandmother in rural Puerto Rico for two years. I was introduced to the people of Carolina, which was and still is a Black town steeped in African tradition. I was nine or ten. I had just arrived from our apartment in the South Bronx. Sitting in the doorway and listening to my grandmother and friends tell stories, I couldn't take part in the conversation, but I was all ears. That world was so new and alien that I was glued to those stories. It was a great lesson in storytelling for a future author.

When did you start writing your own stories?

"I got tired of watching stereotypical images and stories told about our lives."

Until I got to college and read 'Down These Mean Streets,' by Piri Thomas, I had never read anything by a Puerto Rican writer. By the time I graduated, I started feeling uncomfortable with the stories about my people as they were presented in the media. I got tired of watching stereotypical images and stories told about our lives. The women were portrayed as either totally submissive or oversexed. The men were either violent gang members or lazy bums. These images were usually deprecating and had no relation to the people I saw in my life. I thought it was time for someone to tell a more realistic tale of who and what we are.

When did you decide that you wanted to write full-time?

I'd dreamt of writing full-time since I was a junior in high school. In my forties, I started thinking of the kind of life I'd like to have when I retired and started planning for it. I went to creative writing workshops at the Westside Y, the John Oliver Killens Workshop and the Bronx Council of the Arts. I knew how to be an English teacher and I knew how to write, but I didn't know how to be a writer. By the time I was fifty-five, I had published short pieces in several literary magazines. Four years after I retired from teaching, my first novel, "Daughters of the Stone," was published. I am now a full-time writer.

How did you get the idea for 'Daughters of the Stone?'

When I visited Puerto Rico, the ladies would always come and tell me stories, and they started going further back to World War II, and even earlier. I started collecting these stories, thinking that I was going to write a memoir of what my family told me. But everybody remembered things differently, so I decided to write fiction.

I started doing research and noticed that my great-grandmother left land to every one of her eleven children. They each had a farm. I thought, 'Where did great-grandma get all that land?' The only way is if a white landowner gave it to her. That's how I got the idea for Fela, the enslaved African who arrives in Puerto Rico at the beginning of the novel. What would she do to protect the land? What power did she and her future daughters have to protect themselves? That's where African religion came in.

The paperback edition of 'Daughters of the Stone' has been taught in twenty-six colleges in the U.S. How important was it for you to achieve this goal?

For me, this is perhaps one of the most rewarding aspects of the book's journey. It's touched the lives of so many young people, of all kinds, who never experienced the world of the novel but who found enough in the narrative to find themselves within its stories.

I hope they take away the notion that the past can offer a way of maneuvering the present and planning for the future. I hope that they can see how they can find strength in the experiences of their ancestors.

'A Woman of Endurance' tells the story of Pola, a minor character in 'Daughters of the Stone.' Why did you create a novel around her?

With every book I give myself another challenge, one that will force me to step out of my comfort zone. Pola is a negative minor character in 'Daughters of the Stone.' With 'A Woman of Endurance,' I gave myself the challenge of making her compelling.

In 'Daughters of the Stone,' I had five protagonists and told the story of a whole line of women. Because it covered a hundred and fifty years and so many characters, I couldn't stay with any one for very long. In 'A Woman of Endurance,' I focus on one protagonist and her journey. I really explore who she is and what makes her tick. It was my way of growing as a writer.

'A Woman of Endurance' is a novel about slavery, yet there are almost no white characters. Why is that?

"I love the saying, 'Every time an elder passes away, we lose a library.'"

This book is about a community of enslaved Afro-Puerto Rican people and the diversity within that community. There are people who support and people who destroy. Some are scholars. One of the main characters is a Muslim who was traveling between universities when he was captured by slave traders. There are characters who never learned how to speak Spanish correctly and those who take pride in their language skills. There's a Black albino who feels, 'I'm even whiter than the white people.' I wanted to explore the slave community, not as a monolithic thing, but as a diverse community of all kinds of people.

Tell me a little bit about your process.

I meditate and out of my meditation my stories develop. I'm not doing this alone. I'm telling the stories of my ancestors. I use mediation to ask questions like, 'What is this character doing? What do they want?' I believe in synchronicity, intuitive knowing and dreaming.

I use my skills, but my stories come from somewhere else, and I don't know where that is. But I trust that they are true. And I've found that when I write stories and then do the research, they're right.

Why is it important to you to honor ancestors and elders?

I love the saying, 'Every time an elder passes away, we lose a library.' I set up a fellowship for women over fifty for writing programs. I also teach Wisdom Workshops to give seniors tools for writing their stories.

One workshop exercise is to write a letter to your great, great-granddaughter about a life lesson you think she should know. Another is to write about an object you want to leave to her and why this particular thing represents you. Our elders' stories speak to endurance and strength. That's what all our ancestors have left us, the notion that we will overcome.

What do you want to achieve with your writing?

I write to give voice to the other that has been silenced. I want to give a voice and a face to the Afro-Puerto Rican community that has never been acknowledged by society. I want to capture a life that is long gone historically, but one that remains the foundation for who and what we are today. I want future generations to know they have this tradition as a rock-solid base.

But I don't only write for Afro-Puerto Ricans. I write for anyone, in any culture, who has been treated as 'the other' and denied a full spectrum identity. I intend to change our national dialogue to include more voices and more images.