Discovering the Holocaust: A Shattering Lesson Learned by a Young Girl

In recognition of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the author reveals how she inadvertently found out about the Holocaust in 1962, at the age of 12

Editor’s note: This story was originally published on Next Avenue in January, 2022.

Growing up in Mt. Airy, a working-class Philadelphia neighborhood comprised equally of Jewish, Catholic and Protestant neighbors, I grew up unaware of the world-shattering genocide known as the Holocaust.

What prompted my Jewish parents to fail to reveal the Holocaust to me?

Deborah E. Lipstadt's 1996 article, "America and the Memory of the Holocaust, 1950-1965," in the Journal of Modern Judaism, suggests that a combination of forces led my parents and other postwar American Jews to dodge the topic entirely.

She writes, "Throughout the 1950s and most of the 1960s [the Holocaust] was barely on the Jewish communal or theological agenda." Lipstadt posits that postwar America, with its new-found prosperity, was simply "not ready to confront the issue."

Whatever my parents' reasons were, my personal discovery of this horrifying historic event, as a twelve-year-old child, coincided with Hannukah 1962, which began at sunset on December 21st.

My Well-intentioned Expedition

I intended to surprise my parents at sunset that Saturday when we would light the second Hanukkah candle. But my plan entailed breaking rules by straying way too far from home to get to the Gimbels Department store at Philadelphia's city line. I had to cross the busy intersection of Cheltenham Avenue and Upsal Street, a mile from my house. The store, the distance, and the intersection were entirely off-limits for me.

But that December day, wings had sprouted inside the oversized pocket of my fashionable dolman- sleeved buffalo plaid jacket, where two curled ten-dollar-bills seemed to flap, propelling me towards my mission.

The money, like the jacket, had been a gift from my Brooklyn-born Tanta Rose, and her husband, Uncle Joe Leitner, who owned Leitner Furs and Uniform Shop in Manhattan. Uncle Joe had slipped the twin bills in the pocket of this jacket he'd designed for me. In his thick Yiddish accent, he'd kissed my forehead whispering, "Do something nice with your gelt (money), Suselah." And so I would.

A Horrifying Encounter

Having safely crossed the busy intersection, I entered Gimbels lower-level side door, encountering the book department, with its spacious wide aisles and broad pedestals stacked high with current books.

Planning to dart up the escalator to the main level to buy a scarf for my mother and a flannel shirt for my father, I was immobilized mid-stride by a display on the center pedestal. There, arranged in soaring pyramids, my eye landed on the two featured books.

I was riveted in place, my eyes glued on these images with the innocent and morbid fascination of a child.

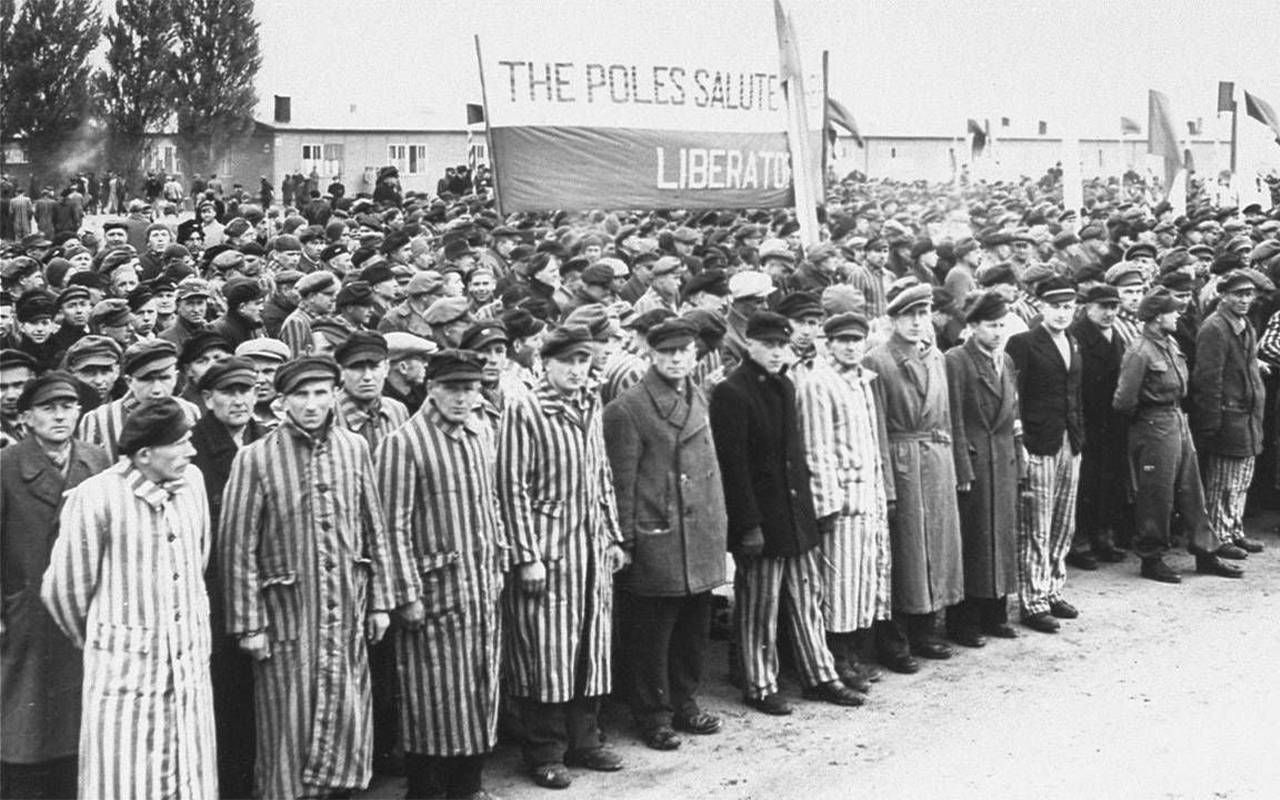

The cover of one presented ghastly, emaciated creatures wearing striped clothing festooned with large Jewish stars. The other, a much larger book, was opened to a center spread of grainy black and white photos of skeletal humans, guarded by men with rifles, or stacked in heaps.

I was riveted in place, my eyes glued on these images with the innocent and morbid fascination of a child.

As I beheld these repulsive confirmations of atrocities, hot fear and anger surged through me; shock and a sense of betrayal burned from the pit of my stomach up to my heart. Until that moment, I was entirely innocent of the Holocaust. I was held as if by an evil sorcerer's spell.

Unable to stop myself, I turned pages, transfixed. Hollow-eyed, hairless men, some wearing those striped suits, others with naked sunken chests, stared from the pages directly through me. Emaciated women and children in various poses appeared, page after page. But it was the stacked skeletal bodies, on carts, in ravines, or heaped on the ground that most assaulted me.

My bold, disobedient spirit leaked tears that splashed onto the glossy paper. My mind raced to understand. The words "exterminated," "Jews," "Nazis," "concentration camps," and "horrors," peppered the captions.

Suddenly, a hand gripped my upper arm, ripping me away from the horror before me.

"Little girl," a sharp voice pierced me, "Where is your mother? You shouldn't be here alone. This is not for children." The book clerk, an older matronly woman, meaning well, only terrified me more.

Softening slightly as she perceived my shock, she steered me towards the cashier station, scanning the aisles for any sign of a missing, inattentive mother.

Not for children pinged through my brain as I wiggled to free myself from her grasp. "Now you stay right here," she admonished. "What's your name? I'm going to page your mother," she said, reaching for the black phone at the desk.

Seizing the opportunity, I bolted, racing up the escalator, making a beeline for the large front doors, sprinting, carelessly crossing the wild six lanes of traffic, running the entire mile back to my front door.

Confrontation with My Parents

My heart pounding in my ears, hot tears scalding my eyes, I thrust the front door open so hard that the brass knob dented the facing closet door. The bang matched my anger; the dent remained forever.

Almost dropping the ubiquitous cigar planted in his mouth, my father jumped from his chair. Enveloped in her easy chair, my mother also rose. Both were stricken by my wild entrance.

My heart pounding in my ears, hot tears scalding my eyes, I thrust the front door open so hard that the brass knob dented the facing closet door.

And then I screamed. A bloodcurdling yell from some primal place no child should ever visit.

"Why were those people…? Who were those Jewish people…?" The words wouldn't match my enflamed thoughts.

My father assumed I had been harmed in some way and raced to gather me up in his arms. My mother mustered as much concern as she was able. Postpartum depression sadly had rendered her a taciturn observer to our life together.

I pulled abruptly away from my father, something neither of us was accustomed to. My father was my beloved protector and provider. He was both mother and father, dependable, loving and until that moment, I thought truthful.

How could there have been an event that warranted two books – a horrific massacre of Jewish people, and I hadn't been told?

A New Understanding

For me to explain where I'd seen these horrors, I had to admit that I'd disobeyed my parents and had traveled farther than allowed – alone. But that transgression paled in comparison to the one I believed my father had made – keeping a secret of such importance from me.

Though loving, kind and responsible, my father, a first-generation immigrant, had only gone to the third grade to work to help support the family. He felt unequal to the task of discussing such momentous annihilation and was careful in handling my traumatic reaction.

Acknowledging that I had meant well by wanting to spend my own Hanukkah gift money on him and my mother, he gently reprimanded me and asked if we could wait to talk, negotiating a deal. I would not be in trouble for disobeying, and I wouldn't punish him for not teaching me about the Holocaust.

The next day he rang up my principal, his friend, to seek advice. On that Monday, I was called to the principal's office at Pennypacker Elementary, where to the best of his ability, Mr. Israel Lerner, explained an abridged, child-appropriate version of the Holocaust to me.

The real gift that Hanukkah was that I came to understand the different ways parents try to protect their children. And my father learned that his daughter deserved the truth about many of life's difficulties.

A Day of Remembrance

January 27, 2022 is International Holocaust Remembrance Day, designated since 2005 by the United Nations General Assembly to commemorate the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. On this annual day of commemoration, the UN urges every member state to honor the six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust and millions of other victims of Nazism, and to develop educational programs to help prevent future genocides.

This message takes on a critical importance given the astounding rise of Holocaust denial and American antisemitism. According to the American Jewish Committee's annual "State of Antisemitism in America" report, released in October 2021, "nearly one out of every four Jews in the U.S. has been the subject of antisemitism over the past year."

Equally disturbing, "out of fear of antisemitism, 39% of American Jews changed their behavior in the past 12 months, such as by avoiding posting online content or wearing items that would identify them as Jewish."

Was this the same fear that motivated my Jewish parents to not disclose the Holocaust to me?

The UN's recommendation, and the work of the United States Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., to develop education programs to help prevent further genocides have never been more vital. We must never forget.