Don't Let Eye Problems Keep You From Painting

Artists with compromised vision have dazzled the world

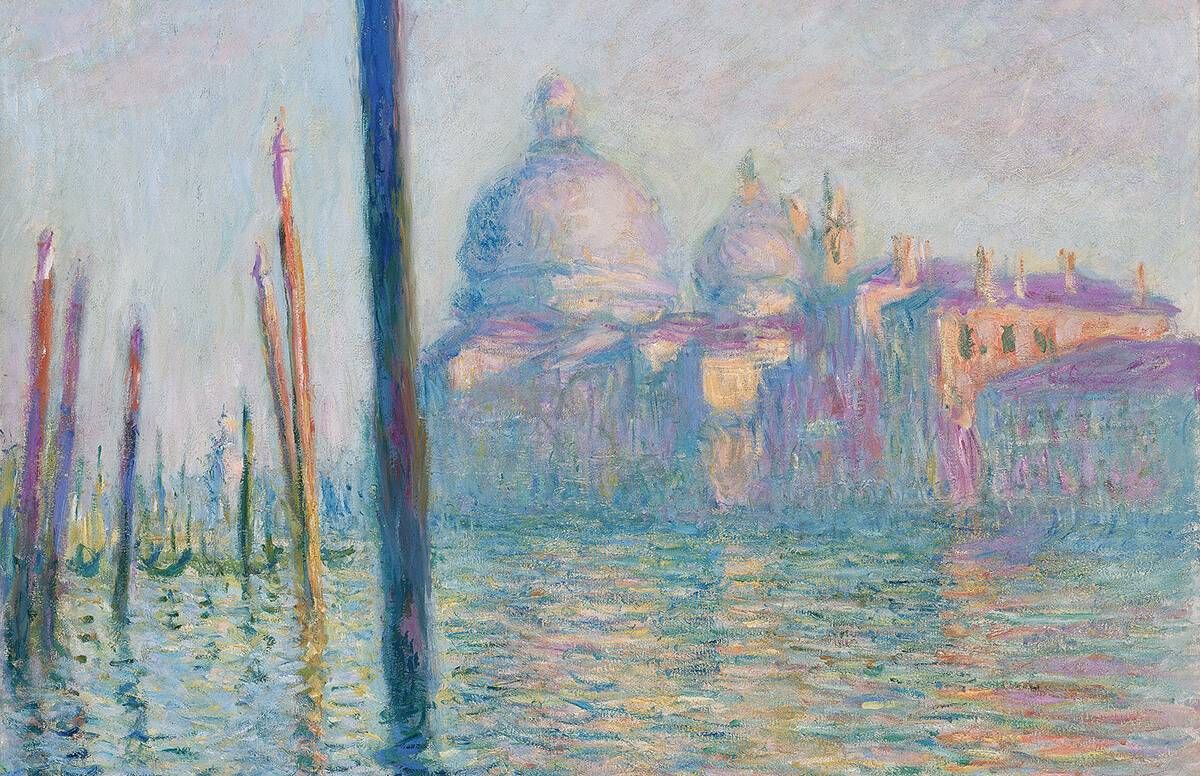

Eager to paint or draw, but concerned that encroaching cataracts or other disabling eye conditions may affect your art? Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, Claude Monet and Georgia O’Keeffe all suffered from compromised vision and, in some instances, painted anyway.

“An impaired artist must compensate, and ideally would be aware of exactly what the specific visual loss means to the art,” said Dr. Michael F. Marmor, professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University. “If making art interests you, I’m in favor of people extending themselves and trying new things, but don’t do it as therapy or because a doctor says to do it. Make art because it fascinates you.”

Marmor has written hundreds of scientific articles on the science of eye diseases and two books about how compromised vision may have affected the work of famous artists. He is the author of Degas Through His Own Eyes and, with James G. Ravin, wroteThe Eye of the Artist.

A lifelong art aficionado, Marmor’s books are “a natural outgrowth of my science and art interests." Also, using computer simulation, Marmor has developed images that show how the later works of Monet and Degas may have appeared to them, as highlighted in a 2007 story in the Stanford Report.

“Poor vision does affect art, though not necessarily all aspects of an artist's concept of his or her work,” Marmor said. “Art is complex, and exists for different purposes, not just as a photographic representation of a scene. It depends on what the artist is trying to portray.”

Artists Who Battled Partial Blindness

What vision-related challenges did some famous artists face?

Claude Monet (1840-1926) developed cataracts in his right eye in 1912, some 30 years after the height of the Impressionist movement. Though the disease affected his ability to see colors, he did not undergo surgery until 1923, when he was nearly blind. In the interim, Monet worked on 12 paintings of water lilies, commissioned by a museum in Paris. Marmor reports that Monet hoped the vast canvases, still hailed as masterpieces today, would serve as a "haven of peaceful meditation" for those who viewed the paintings.

Diabetes stole the eyesight of Mary Cassatt (1844-1926). An American painter and printmaker, Cassatt moved to Paris in 1866, where she befriended and became a colleague of Degas. She later exhibited with the Impressionists, and by 1900, Cassatt was a role model for several young American artists and also served as an adviser to major art collectors. By 1915, her failing eyesight caused her to give up painting, which she had described as “her greatest source of pleasure.”

Edgar Degas (1834-1917) suffered from a retinal eye disease that Marmor notes frustrated the artist for the last 50 years of his long career. “You can see how his pastels degraded over time in terms of facial detail and other aspects, but because he was dealing with large subjects — a woman in the bath or a dancer — Degas continued to see well enough to perceive his subjects,” Marmor said. “I would speculate that even with his blurry vision, Degas could appreciate how raw these pieces would look to us.”

Recognized as the “Mother of American Modernism,” Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) is best known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, polished animal skulls and landscapes in New Mexico. O’Keeffe first experienced eye problems in 1968, and three years later, macular degeneration had caused her to lose all her central vision. She stopped working in oils, but continued to paint watercolors for a few more years.

Though the visual impairments of these artists have been well documented, Marmor said he wonders how much these creators thought about the difference between what they painted and what viewers see. His simulations led him to question whether the artists intended later works to look exactly as they do.

“How much did Monet or Degas think about this? Monet’s abstract works are strangely garish — what was he trying to do?" said Marmor. "He never told us, so it’s hard to say.”

How Contemporary Blind Artists Compensate

John Bramblitt, a contemporary artist who lives in Denton, Texas, is completely blind. In 2001, at the age of 30, he lost his vision due to complications of epilepsy and Lyme disease. Though Braille on paint tubes identifies individual colors for him, Bramblitt says the assorted colors also have varying textures and each feels different to the touch. He also works on canvases with raised lines.

Bramblitt's art has been sold in more than 120 countries and his work has been featured in print, on television and on radio programs around the world. He is the subject of two short documentaries, Line of Sight and Bramblitt, and he has been honored with three Presidential Service Awards for his art workshops. Also, he is the author of Shouting in the Dark: My Journey Back to the Light.

“In a way, I am glad that I became blind,” Bramblitt wrote. “This makes more sense when you stop thinking about adversity as an obstacle, and start viewing it as an experience — something that you can learn from and grow from.”

Henry Butler, a blind jazz pianist who died in July 2018, also is celebrated for his photography skills. Butler’s pictures are featured in the documentary Dark Light: The Art of Blind Photographers and his work is part of “Sight Unseen: International Photography by Blind Artists,” a touring exhibition.

In November 2017, Butler gave a talk at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, in New Orleans. “Henry Butler says that if he doesn’t try things that everybody can do, then he is not living a full life,” said Marmor, who sponsored Butler’s address.

Marmor's advice: “Anyone with a visual impairment who wants to take up art should think about his or her personal image of what they want to do. It may be a challenge, but if you have ideas about what you’d like to say, say it.”