The Signature Story Quilts of Artist Faith Ringgold

An appreciation for the 92-year-old African American mixed media artist, activist and role model who continues to live creatively

For Faith Ringgold, the 92-year-old mixed media artist, necessity was the mother of invention when it came to creating the story quilts that made her famous. After a couple of decades painting large works on canvas, she realized that those paintings were too big for her to handle by herself and difficult to cart around and ship.

But if she worked on fabric, she could roll up her soft canvases and easily tote them single-handedly and mail them, when needed, "like her daughters' clothes to camp," as she joked.

Today, Ringgold has been having a major moment at museums around the country. This richly deserved, coast-to-coast attention has built slowly and steadily over decades, powered by her virtuosity and persistence. She is also among a growing number of African American artists who are finally and rightfully in the spotlight after the racial reckoning that has prompted curators nationwide to diversify their rosters.

"Faith is a force of nature whose art is imbued with a commitment to social justice in every stroke."

Ringgold's dazzling work is being showcased from New York City (The New Museum in 2022) to Chicago and Miami (The Museum of Contemporary Art and The Bass in 2023) to San Francisco, where last year I had the pleasure of seeing her career-spanning retrospective, "American People," at the de Young Museum

As I toured the exhibit, I was wowed by Ringgold's eye-popping rainbow use of color, her political passion, and most of all, her inventiveness. It's this genius for invention that has inspired her sixty-year creative life as a multi-hyphenated artist who has amazingly worked in sixteen different media — from painting to soft sculpture, from political posters to costumes for performance pieces and masks inspired by African tribal face coverings.

"She's complex and has an amazing work ethic," says Dorian Bergen, her longtime gallerist at the ACA Galleries in New York City and friend of almost 30 years. "From the moment we met I was impressed with her vision, her perseverance and her generosity to others. Faith is a force of nature whose art is imbued with a commitment to social justice in every stroke."

Her Signature Story Quilts

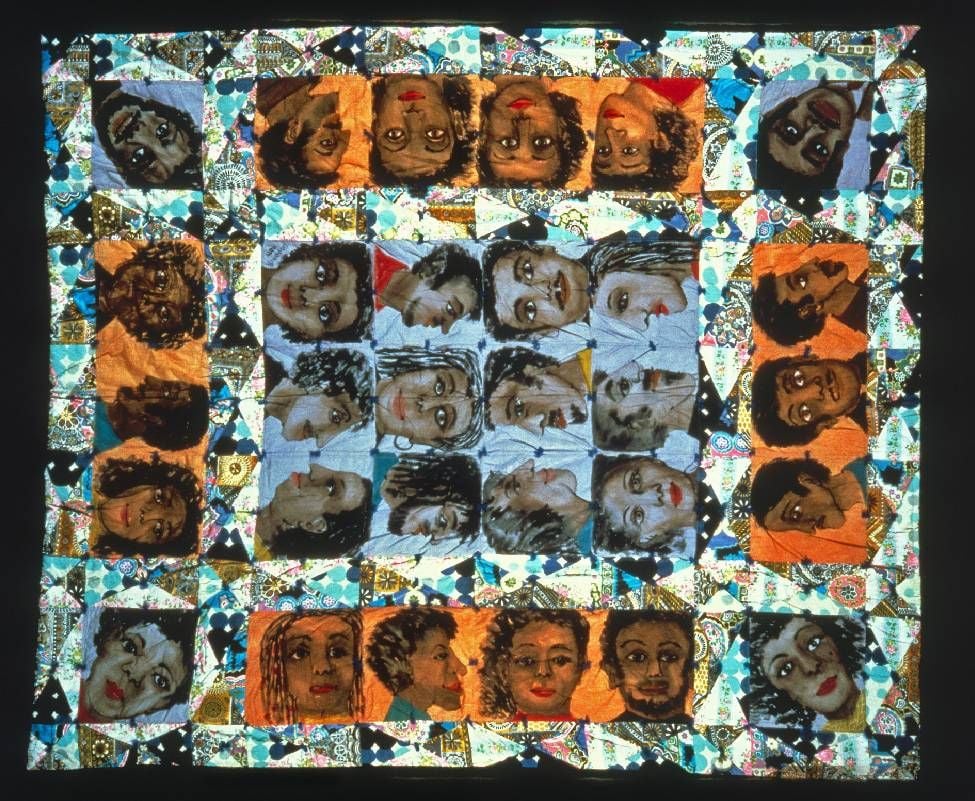

Ringgold is best known for her story quilts, the art form she pioneered that marries vivid imagery, painted and collaged fabric, and text. It's a word-and-image medium that has become her signature.

In the de Young exhibit, these richly layered and original textiles surround the viewer with bright bursts of jeweled color — brick reds, intense turquoises, sunshine yellows — plus witty, whimsical designs and an overview of African American heroes and history that teach better than textbooks. These fabric works revive the historic African and African American art of quilt-making, harking back to quilts slaves brought with them from Africa that were both useful and a creative statement.

Many of the quilts memorialize legends of the past like Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks and Shirley Chisholm — and more recent legends as well. In 1989, Oprah Winfrey commissioned Ringgold to create a birthday quilt honoring the life and works of her mentor, the writer Maya Angelou. After Angelou's death, "Maya's Quilt of Life" sold for an impressive $380,000 to the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Meet Willa Marie Simone

When Ringgold first started creating quilts in the 1980s, she was also trying to sell her autobiography. After every publisher she approached turned it down, she wouldn't take no for an answer. Never mind the publishing industry, she figured, she could simply include her personal stories on her quilts. She invented an alter ego to speak for her whom she named Willa Marie Simone and took her on adventures all over France, from Paris to Giverny and Arles, producing a series of charming and evocative quilts called "The French Collection" in the 1990s, several part of the de Young show.

Willa's travels were inspired by the influential 1961 trip Ringgold had made to France with her mother and her two then-young daughters, Michele and Barbara. Other stand-out story quilts in the show share social commentary, like the triptych "Street Story Quilt" about urban life in a tenement, and still others, like the autobiographical "Change," document Ringgold's forty-year loss and gain of 100 pounds.

Almost a Century of Making Art

Although Ringgold did see her memoir published in 1995 as "We Flew Over the Bridge," she had hit upon a winning combination of art and words: she continued to include panel after panel of storytelling in tiny, even script around the quilts' borders. In the recent de Young exhibit, you could scan a QR code on your phone to get a transcript of the stories on every quilted fabric piece, a contemporary adaptation that the artist probably hadn't envisioned forty years earlier.

The family lived on 146th Street in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance surrounded by illustrious neighbors — Thurgood Marshall, W.E.B. Dubois, Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes.

Like Georgia O'Keeffe, another iconic woman artist who lived into her 90s, Ringgold has lived and made art for almost a century. She was born in 1930 to parents who encouraged her creativity from an early age. Because she had asthma as a young child, she was often homebound and her mother, Willi Posey Jones, a fashion designer and seamstress, gave her scraps of cloth to play with, prompting the artist's lifelong love of making things out of fabric. Later they'd collaborate on Ringgold's first quilt, "Echoes of Harlem" in 1980. Her father's gift of her first easel that he propped up on her bed prompted her lifelong dedication to drawing and painting.

The family lived on 146th Street in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance surrounded by illustrious neighbors — Thurgood Marshall, W.E.B. Dubois, Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes. Malcolm X lived on Ringgold's corner, and the saxophonist Sonny Rollins was her next-door neighbor, a frequent guest who'd come over to blow his horn in her apartment. In 1986, she conjured him in a stunning quilt, "Sonny's Bridge," his tall, lanky frame standing high on the George Washington Bridge, playing his sax against a deep blue quilted night sky dotted with skyscrapers, a gem of the de Young show.

In 1991, Ringgold immortalized her childhood apartment building in a story quilt also featured in the San Francisco exhibit and in her first children's book, "Tar Beach." She named it for the building's tar rooftop where the family picnicked on hot summer nights. Visually stunning with her own illustrations, showing her young heroine, Cassie Louise Lightfoot, flying above the rooftops, among the stars, "Tar Beach" received more than twenty awards including the Caldecott Honor, the Coretta Scott King award for illustration, the NY Times Best Illustrated Books of the Year and became a Reading Rainbow selection.

She has since illustrated twenty other children's books, including "If A Bus Could Talk: The Story of Rosa Parks" and "Aunt Harriet's Underground Railroad in the Sky." Her playful, vivid illustrations bring these stories of African American history to life and inspire a new generation of children.

A Champion for Black Women Artists

Ringgold found her voice and made political art during the Civil Rights struggles and Black Power Movement of the sixties, and she was an early spokeswoman and champion of the women's movement. Some of the most arresting pieces in the de Young show are her bold black, red and green political posters for Angela Davis and the Black Panthers from the 1970s.

Perhaps the most iconic piece from this era is the chilling twelve-foot long 1967 canvas, "Die," as outsized and gut-punching as Picasso's iconic anti-war painting, "Guernica," which Ringgold studied at the Museum of Modern art as a model. Her painting evokes the civil uprisings of the time with both Black and white people, adults and children, running wildly, as if in a riot, blood splattering in all directions. It's hard both to look at and to turn away from. Anguish and anger burn off the frame.

Her refusal to take no for an answer has empowered her, and her decades of activism have opened doors for younger artists.

In 1968, Ringgold started demonstrating against the Whitney Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City to show the works of more Black women artists. In her memoir, she called 1970 her first year of becoming a feminist, spearheading a group called Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation. They protested against the Whitney annual Biennial, demanding that 50% of the artists be women; 23% women were chosen, better than the previous 10%, but not the balance they argued for. More than half a century later, this fight for museums' fair representation for women and artists of color is still being waged.

But Ringgold's star has increasingly risen since those early days of knocking on institutional doors. She has been exhibited hundreds of times, had a long career as an art professor at University of California-San Diego until retiring in 2002 and was awarded 23 honorary doctorates.

Ringgold is still producing art in her studio in Englewood, New Jersey. But more than anything, she's been a beacon and role model for other artists, especially women and creators of color, to keep making art despite obstacles and resistance from the old guard. Her refusal to take no for an answer has empowered her, and her decades of activism have opened doors for younger artists.

In an interview before last year's show at the New Museum, Ringgold summed up her near century of advice: "Find your voice and don't worry about what other people think."