The Family Doctor and the Coronavirus Plague

Dr. Bertie Bregman argues for keeping primary care practices open during COVID-19

“I have no idea what’s awaiting me, or what will happen when this all ends. For the moment I know this: there are sick people and they need curing.”

-Albert Camus, The Plague

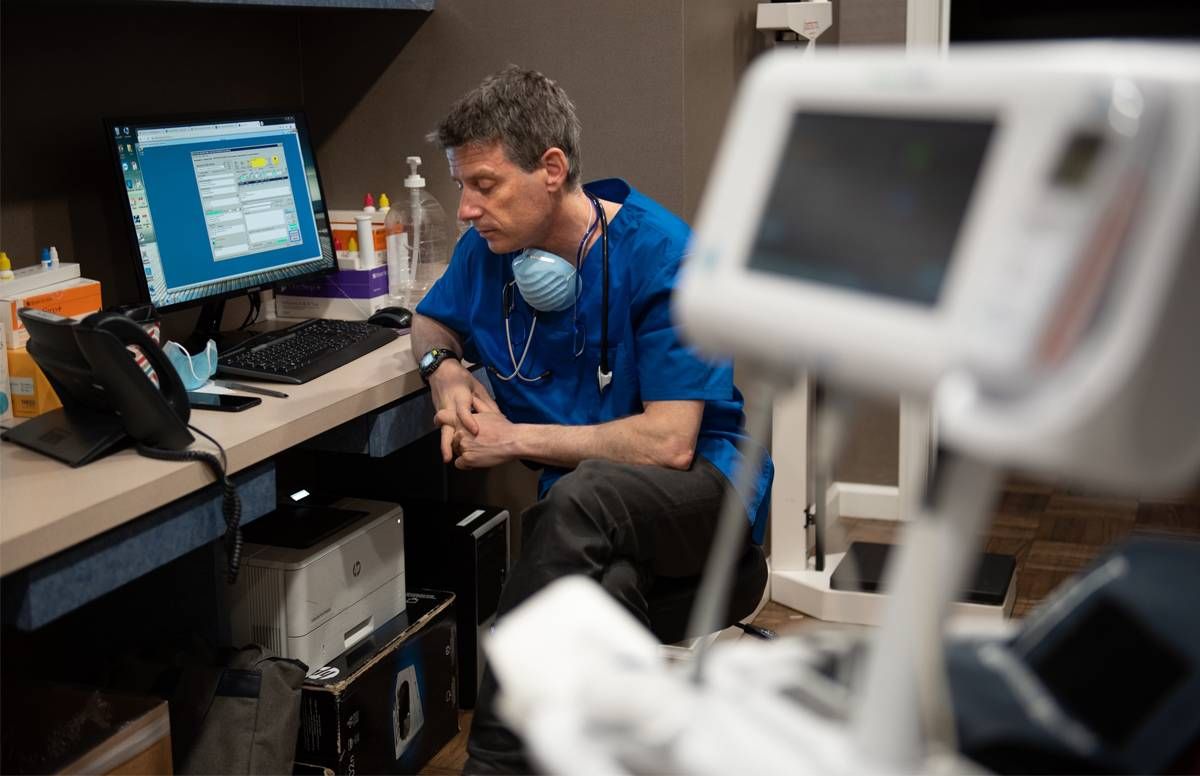

Dr. Bertie Bregman wrote his college thesis on Camus and The Plague, and now he’s a doctor living through one.

“One of the lessons of The Plague and of existentialism in general,” he said on Good Friday, between multiple telemedicine calls and an in-person exam of an entire family battling COVID-19, “is that what’s really important is how you live your life, the actions that you take, the tangible choices that you make on a day to day basis.”

The 3 Hats of Dr. Bregman

Bregman is normally a primary care physician, but during this particular plague he’s been wearing several hats.

The first (but not totally unexpected) hat was the one he wore as one of New York City’s first COVID-19 patients.

Now that he’s on the mend, hats number two and three have him spending the majority of his days at one of his three primary care offices in Manhattan as well as several hours during the week trying to cut through the red tape in New York’s byzantine, decentralized hospital system to set up regular hours working shifts in the emergency room of Columbia Presbyterian’s Allen Pavilion. That’s where, last week, 23 out of the 25 patients he saw were battling COVID-19.

Whatever minutes he has left in his day are devoted to spending time with one of the other doctors in his private practice, who also happens to be his wife, and helping to parent their five children, all of whom, he believes, must have caught the virus from him but are asymptomatic.

“There’s no way they didn’t catch it,” he said. “But they’re all doing well. My youngest is actually psyched. He’s never played this much Fortnight in his life.”

Snap Judgments on the Phone

Many of Bregman’s office hours have been fraught with making snap judgments based on how his patients sound over the telephone.

“Okay, I want you to take a deep breath in and when you breathe out, I want you to count from one to thirty. Can you do that?” he said to one of his probable COVID-19 patients, who started counting so slowly that Bregman began to laugh.

“No, no, no, you’ll never make it to thirty that way. Try it fast, like this: 1–2–3–4–5…”

Our Commitment to Covering the Coronavirus

We are committed to reliable reporting on the risks of the coronavirus and steps you can take to benefit you, your loved ones and others in your community. Read Next Avenue's Coronavirus Coverage.

By the end of the call, he determined that this patient was doing well, or at least well enough to stay away from the overwhelmed hospitals, and that he should continue recuperating at home with his girlfriend, who’d also fallen ill.

Bregman also fielded a call from a patient who was not sick with COVID-19 but whose anxiety had become so disruptive to her sleep and daily life that her Wellbutrin was no longer working.

“Okay, I’m gonna prescribe a low dose of Lexapro as well,” said Bregman. “That should help.”

A third patient was managing crushing headaches. A fourth was worried about staying sober.

The Problems With Telemedicine

At first, Bregman tried charging these telemedicine calls to insurance, when insurers promised they would cover such calls, to keep patients safe, but he’s yet to see evidence of this change in policy.

“A lot of those telemedicine claims are getting rejected, or the whole thing goes through the patient’s deductible. Or they do have to pay a copay because…who knows why? The reality of what insurance companies are doing and what they’re saying they’re doing, there’s a big disparity there,” said Bregman.

Bregman is my primary care physician. During my own 18 days of COVID-19 illness, I made three telemedicine calls to his office from my bedroom: two to his partner, when he was sick; one to him, when he was on the mend.

During my last call with Bregman, when I couldn’t count to 30 or even to 5 without collapsing into a fit of coughing, he insisted I come into the office so he could listen to my lungs in person through his stethoscope.

'You're Still Open?'

“You’re still open?” I said. Nearly every one of the primary care offices in my neighborhood has a “Closed until further notice” sign on it.

“Of course we are,” said Bregman.

“That’s unusual,” I said.

During our visit, he listened to my lungs and hooked me up to a pulse oximeter, which gave him two important pieces of data: my lungs were getting adequate oxygen but breathing deeply was still a problem.

He diagnosed RAD — reactive airway disease — a byproduct of getting sick with COVID-19 which should hopefully improve over time. He prescribed prednisone and told me to keep using my nebulizer, my albuterol inhaler, and my Q-var inhaler.

“Right now,” said Bregman, “it seems everything in medicine is either/or. Either, ‘You’re sick enough to be in the hospital’ or ‘Don’t go to your doctor. Use telemedicine.’ But telemedicine has its limits. You’re the perfect example of somebody who we have to see in person because the alternative, if you’re just going to do telemedicine, is to send you to the hospital because you have someone who probably has coronavirus, who could get really sick, and who’s having prominent and fairly severe respiratory symptoms. You can’t just say, ‘Oh, don’t worry about it. It’ll be okay.’ Maybe it won’t be okay.”

Meeting His Patients Face to Face During COVID-19

Next, Bregman examined the lungs of Victor Portelli, a building superintendent, as well as those of Portelli’s wife and son, all of whom have come down with COVID-19. “You guys are doing great,” said Bregman. But he was concerned about some wheezing in Portelli’s lungs. “Victor, are you still smoking?” he said.

“Sometimes,” said Victor, “but I’m trying to stop.”

“Victor!” Bregman was firm but kind, delivering his advice with laughter, encouragement, and what felt like love. “If COVID-19 won’t get you to quit, I don’t know what will. That wheezing I’m hearing? That’s from smoking, not from the virus.”

Victor promised to try the nicotine patch. His wife seemed pleased with this decision. The family was told to go home and to keep drinking fluids and getting rest, but to call him immediately if their condition changed.

Bregman believes so firmly in the need to see his COVID-19 patients face-to-face, so he can assess their lungs and witness their breathing in person, that he thinks today’s either/or way of practicing medicine during a pandemic might be contributing to overwhelming our hospitals with patients who should be recuperating at home.

This Physician's Wish

He wishes other primary care physicians would return to their practices as soon as possible, at least to treat possible cases of COVID-19, while reserving the safety of telemedicine for their patients’ other maladies.

“The most important thing that we can do as physicians,” he said, “is to keep patients out of the emergency room and out of the hospital who don’t need to be there. We’re family medicine doctors. We should be the first line of defense for anybody for anything, because we can either treat it and take care of it ourselves, or, if not, we know exactly where to send the patients, so they get the best care.”

This is particularly important, Bregman believes, in a country like ours with a decentralized medical system, where red tape is a feature not a bug.

“We have a pretty bad public health system in the U.S. overall, particularly with regard to the coordination of care between private doctors and public doctors, and doctors working at hospital systems and doctors in private practice, and people with insurance and people without insurance. In a place like France, they don’t really have those issues because everybody’s working within the same system,” he said.

Why Some Doctors Haven't Returned to the Office

One of the main problems in getting primary care physicians in U.S. coronavirus hotspots to return to their offices, Bregman believes, is that many primary care practices are now, ironically, failing financially.

One of his colleagues closed his office when his patient numbers diminished to less than 5% of his normal caseload. During the pandemic. Bregman said, “Many doctors simply closed down their offices from some combination of, ‘We don’t have enough patients’ and ‘We don’t want to expose ourselves and our staff to coronavirus.’”

But Bregman, like Camus’ protagonist Dr. Bernard Rieux, is determined to keep his doors open, despite the dangers and logistical challenges COVID-19 presents.

“The most important lesson from The Plague — and you see this in the character of the doctor — is that to be a moral hero doesn’t require grand gestures. It just requires that you do your work at a time like that, that you show up for work. You just see patients, and you don’t turn your back. You don’t run away. You don’t leave. You don’t come up with excuses. You just do your job.”

A COVID-19 Stop at the Hospital

After finishing up with the Portelli family, Bregman shut the doors of his private practice and was about to head north to the hospital. But first, he wanted to stop by the overflow COVID-19 tents in front of Mount Sinai Hospital in Central Park to offer his services.

“Do you guys need help?” he said to the security guard blocking the entrance. “I’m a doctor. I work nearby. I’d like to volunteer to help.”

“I’m not the one you need to speak to,” said the security guard, “but if you go on the website, I’m sure they have lots of information there.”

Bregman’s eyes, staring up at the grey sky from his mask, spoke volumes: of course, more red tape, why should today be any different?

“Thanks,” said Bregman, “I’ll figure it out.”

Then the doctor turned and headed north to try to save more lives.

(This article originally appeared on Medium.com.)