Forgiving a Parent You Love to Hate — Even After Their Death

It wasn't until after she was gone that I realized how complicated my mother was, and how her vulnerabilities impacted her love for me

To escape from a toxic relationship that's got you in its grip, you need an understanding of it that's more complex and truer than the one you came up with as a child.

When Nelson Mandela, the first Black president of South Africa, emerged from prison after 27 years, he famously said he couldn't be truly free unless he let go of his hatred for his jailers. You don't have to have been unjustly imprisoned — or to have experienced anything remotely comparable — to know what he meant.

Like most adult children with an unloving parent, I was trapped in a relationship with my hyper-critical mother, no matter how far I was from home, in miles or years. She lived in my mind, in my nervous system. I could hear her putdowns without her saying a word. And her hostile pronouncements continued after her death.

Until I could turn off her voice in my head, nothing I accomplished would ever make me feel adequate.

I know from experience that, while you cannot change what happened in a relationship, you can change how you understand what happened and, therefore, how it impacts you in the present. You can silence the negative voice. You can forgive what seemed unforgivable.

How to Free Yourself From Someone Who Isn't There

My executive mother worked longer hours than my father, and left my care to a live-in nanny, defining her own role as Fixer-in-Chief. Like any child who's constantly criticized, I assumed that the problem was with me; if I'd been "better" — neater/quicker/prettier — it would have been different.

When I was in my twenties, I learned about projection and realized that my mother saw in me all the flaws she saw in herself. But an intellectual understanding on its own does not bring change. Until I could turn off her voice in my head, nothing I accomplished would ever make me feel adequate.

While my mother was alive, I never had the courage to confront her. "You're so touchy!" she'd say to any small push back. "Do I have to walk on eggshells with you?" I couldn't face the contempt that would follow if I pushed further. And, of course, I carried my bag of fears into other parts of my life.

The solution wasn't quick or easy. It lay in coming to understand my mother as a complex human being — not merely as a flawed mother — of uncovering the source of her bitterness, of cutting her down to size, to human size. I had to accept that my understanding of her, which after all I'd formed as a child, was inaccurate. And I had to correct it. It was a steep climb.

Can You Forgive a Parent You Need to Hate?

I resisted any notion that my mother was not as terrible as I remembered. If, like me, you're angry at having been mistreated, you know how good that anger feels. Vilifying my mother was my revenge and the well from which I drew strength. As a child, I paid her back by seeing her as a cruel witch. That vision was my reality and the frame through which I interpreted everything she said and did.

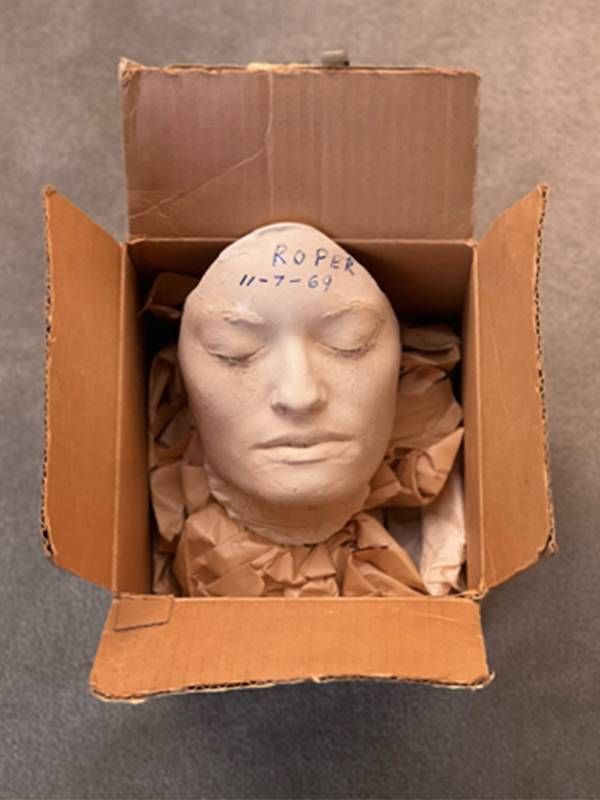

For example, my mother once read about a man fabricating facial casts in a downtown New York City loft and sent me to have one made — during high school, I recalled. It was very cold in the loft, and I had to remove my coat, so the dour, unfriendly mask-maker could cloak me in plastic. He put straws in my nose and smeared Vaseline on my face before applying the cold plaster, while I shivered continuously — until I got home and into a hot bath.

The next morning, my face was covered with impetigo, a nasty, contagious skin disease. When the finished mask arrived, my mother hated it and stuffed it back in the box where it's remained ever since, though now in a closet of mine.

Why would my mother, who was always critical of my appearance, want a facsimile of my face in the first place?

Over the years, I told the story of the mask many times as an example of my mother's imperious style. She didn't care what she'd put me through, and her rejection of the mask felt like a rejection of me. But there was a question I avoided: why would my mother, who was always critical of my appearance, want a facsimile of my face in the first place? At the time, it made no sense.

It wasn't until my mother died that my lifelong view of her developed a crack. Irrational as it sounds, I was genuinely shocked to see that my mother could die. If she was mortal, she was not the indestructible, super-villain I'd imagined. When I started to wonder what else I might have gotten wrong, a more accurate portrait began to take shape.

Creating a More Nuanced Understanding

I forced myself to focus on memories of her that had never quite fit The Witch. My mother could be generous and fun-loving, particularly in a threesome with my father. And then, I could tell she had insecurities — always needing to shop with a chic friend, constantly worrying about her hairdo, hating being photographed — clues I'd noticed without making anything of them.

My mother's anxieties only began to seem real when I got away from my own experience of her. When I read my father's letters to her during the war, I saw her panic that he might not be faithful. From her friends, I learned she'd been convinced she wasn't "woman enough" to be a mother and that she'd been put down by her own mother.

Eventually, I could see that her whole attack mode was a false facade to keep everyone from suspecting how vulnerable she actually felt. Eventually, I realized she'd sensed how I felt about her, and I regretted that she'd died fearing she'd failed me.

Recently, when I dug out my mask from the back of the closet, I was surprised to see its date scrawled across my forehead. It was made not when I was in high school but when I was 24 and about to be married! Apparently, my mother had felt some sense of impending loss at my marriage, and — hard as it was for me to believe — my face, despite all her criticisms, must have been dear to her. It looks like a death mask. No wonder she hated it.

Now, I can see that it was fear of my rejection of her, who was convinced of her own unworthiness, that kept her from showing her love. The hurt she inflicted was real. But a conflicted woman oblivious to the damage she is causing, however unmotherly, is not a vicious monster.

The more clearly I could see the complicated person my mother was, the more the cartoonish, frightening image of her faded. Slowly, her voice in my head retreated. And then one day I noticed it was gone, and I was free.