A Former State Lawmaker Writes to Change the Mental Health System

Mindy Greiling’s new book draws on her struggle to care for her son with schizophrenia

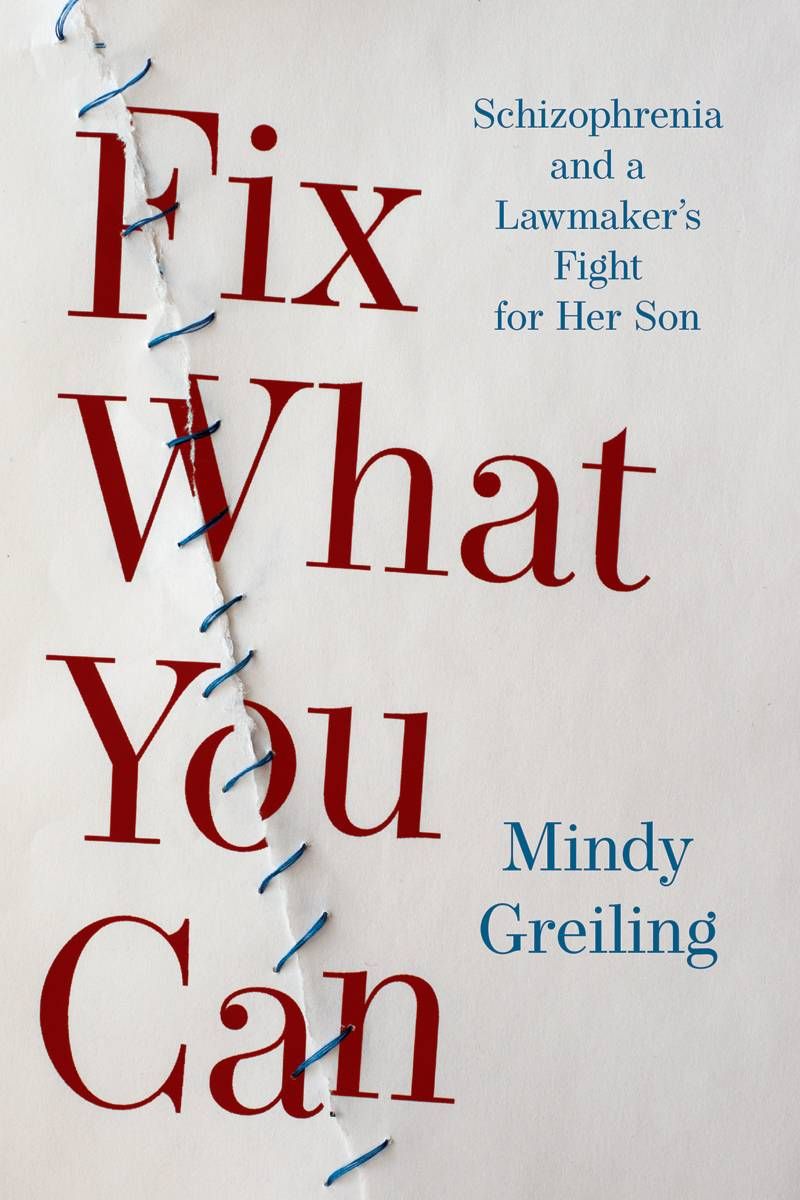

Former Minnesota lawmaker Mindy Greiling hopes her new book will lead to systemic change across the country. In "Fix What You Can: Schizophrenia and a Lawmaker's Fight for Her Son," Greiling tells the story of trying to get care for her son Jim, diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder in his early twenties (he's now 43). She quickly discovered the gaps in the system, pushed for more mental health funding and helped found the nation's first state bipartisan mental health caucus.

Greiling served in the Minnesota House for 20 years as a Democrat from Roseville, a Minneapolis suburb. I first met her more than two decades ago while covering the Minnesota State Capitol, and spoke with her via Zoom about her book.

Next Avenue: You wrote about trying to get help for Jim while you were a state legislator. That was obviously a busy time for you. You were trying to change the system and deal with your son's illness. Why write the book now?

Mindy Greiling: When I left the Legislature, I no longer had a voice in the mental health arena like I had before. I could work with my legislators, I could work through NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness), but I missed having a voice. And so when I was invited to join a memoir group, a writing group at the Loft Literary Center, I quickly felt that I was meant to write this book.

I'd always been a writer and kept a journal. So I had places to go back and help jog my memory. It also then gave me a chance to continue stronger advocacy. There's something that gives you a certain gravitas if you've written a book. And I'm finding that with this book, I'm invited to go places besides Minnesota and talk about the mental health system. What I do best is advocate and advocacy, so I'm just pleased as could be that that's turning out to be the case with this book.

"Now people don't stay put in a state hospital, but we haven't replaced the state hospitals with anything that sustains people."

Even now during COVID-19, you're able to travel and speak, or is it all virtual?

It's all virtual and that's great. I don't have to travel, I can just speak. So it works out even better. This just cuts to the chase.

What are the main things you want a parent who's trying to help a child take away from your book?

The first thing is to get educated. You have to learn about what you're dealing with. You can't cope with the unknown.

So immediately I connected with groups like NAMI, and they have wonderful family programs. They have programs for people new to the illness themselves, too. But, of course, I plugged into the family programs with my husband and read every book I could get my hands on. And then once you're educated, then you need to branch out.

You need graduate level support. Not somebody that you have to keep saying, 'this is what schizoaffective disorder means,' or 'Jim can't help this because that's part of his illness.' You need people that you can talk shorthand to. And then you can help each other. You can connect with your hearts or with information.

How is Jim doing? I could imagine for someone struggling with a serious mental illness during COVID-19, this might be even more challenging.

He's doing really well. And he actually says it doesn't matter. COVID-19 doesn't change his life at all.

His life, with his schizoaffective disorder, even before COVID-19, had shrunk. He likes to spend time at coffee shops, but he was not seeing a lot of people. He likes to see one person at a time. And so the idea now that he avoids crowds, that he doesn't go out as much, that is his life before COVID-19. It actually makes him feel better in some ways, because everybody else is now in the same life he probably always will have.

"This book is my ticket to being able to participate in national discussions."

You also wrote about your grandmother, who had been in an institution for decades. I think you saw that in Jim's situation, he was treated a little more humanely. Talk about the changes you saw in how we take care of people.

My grandmother went to the Rochester (Minn.) State Hospital in 1958 when I was ten years old and she stayed there for twenty-three years, before she was old enough to go to the nursing home. That was definitely not what we wanted for Jim.

But I don't think it's changed that much since those days in some ways.

Now people don't stay put in a state hospital, but we haven't replaced the state hospitals with anything that sustains people. Our community care is pretty much made up of ninety-day programs. You go to the hospital if you're in crisis, then you're in a ninety-day program. Or if it's your chemical dependency, it might be a twenty-eight-day program. And the idea of having a place where people can just live their lives, there are so few spots.

Jim is in his apartment, but it's not supportive housing. There are no staff there. There are no other people that he knows of that have mental illness where he can make friends. So I think it's pie in the sky to think that you can take someone with something like schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and plunk them into an apartment where everybody else is busy, has their own lives and you think they're going to thrive there. It's not happening for Jim. And I don't think it happens for very many people.

Are there a couple of things nationally that are your biggest focus, now that you're speaking to groups all over the country?

One of my causes is more mental health courts. I realize that it would be better for people not to end up in any kind of a court, but we have to be pragmatic with the system that we have. Therefore, mental health courts are so much better than criminal courts. Jim has been in both, so we know the difference. One is treatment-oriented and the other one is really geared to punishment. Their only tool in the tool box, if you don't do what you're supposed to, is spend some time in jail. The mental health court has a lot more mental health resources.

So that's one of my causes, and as we said, affordable housing that's supportive housing for people with mental illness. When I finally can travel, I do want to plug into some of these other groups in other states. There's so much to do with the mental health system. And this book is my ticket to being able to participate in national discussions.

An Excerpt From "Fix What You Can"

I was exhausted. I fingered my petrified-wood power ring, waiting to give my speech. They were given in order of seniority, so I would be near the end. I had served twenty years, fourteen of them after Jim got sick ...

The speaker called my name. I stood, took my microphone. "I'm proud we passed a visionary mental health bill last session, with the most funding in the history of our state." I smiled. "Do right by people with mental illness," I admonished my colleagues. "Or my ghost will roam these halls, haunting you."