The 'Founding Mothers' of NPR

Remembering the radio network's early days featuring Susan Stamberg, Nina Totenberg, Linda Wertheimer and Cokie Roberts

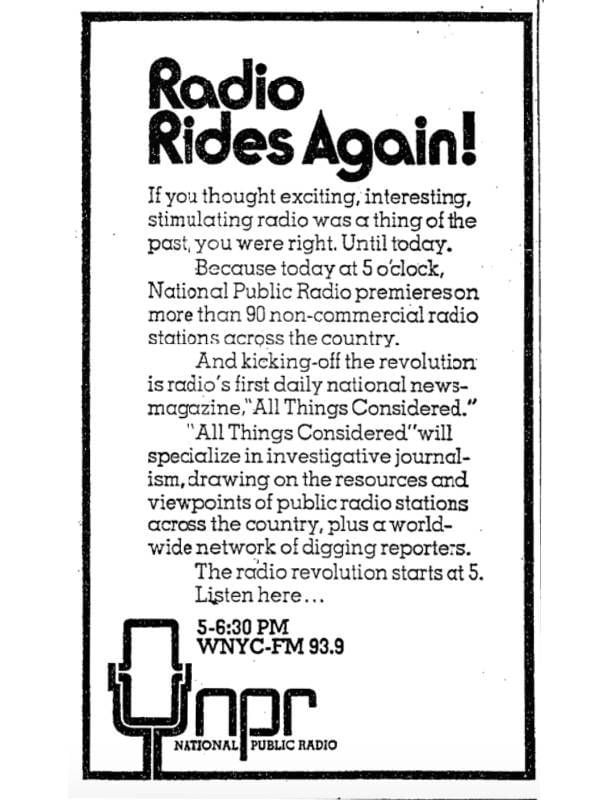

Even by startup standards, this one was barebones. Before the furniture arrived, a handful of employees sat on the floor in a Washington, D.C., office, brainstorming a name for a new national radio program. A few months later, on May 3, 1971, careful readers of The New York Times may have spotted a small ad with a bold promise: "RADIO RIDES AGAIN! ...The radio revolution starts at 5."

So it did. Fifty years ago next month, National Public Radio launched, with a 90-minute afternoon newsmagazine show called "All Things Considered." Pieces on the premiere ranged from a police clash with Vietnam War protestors, poems from World War I and a visit to an Iowa barbershop that shaved women's legs. (Just 75 cents for the first leg; a quarter for the other.) As the name promised, ALL things considered.

"All Things Considered" was a stunning contrast to what much of radio had become: a Top 40 jukebox with top-of-the-hour headlines.

An Uneven Start for National Public Radio

With a tiny staff, the broadcast was a bit uneven in its early days. NPR's first program director Bill Siemering put it this way on an NPR "Founding Mothers" Zoom event last August: "Some brilliant piece and then something so embarrassing we didn't know what to do because the shelf was empty." But in sound and substance, "All Things Considered" was a stunning contrast to what much of radio had become: a Top 40 jukebox with top-of-the-hour headlines.

Siemering (now Senior Fellow with the Wyncote Foundation), was determined that the fledgling radio network hold up a mirror to the country and sound like America — conversational, diverse and distinctive voices, often with more than a hint of regional accents.

"It was thrilling and terrifying," said Susan Stamberg, 82, an early co-host of "All Things Considered" (1972-1986) and the first woman to anchor a national nightly news broadcast. "It was so much fun, maybe more fun than I ever had in my life, because we were inventing something new with almost no resources." (Full disclosure: Stamberg and I were NPR colleagues for years, and she is a longtime friend. I wrote about that time in my Next Avenue article: "Reflections on My Days Working With the Founding Mothers of NPR.")

"Bill was a prophet who told us what we were going to do. He wanted us to sound like regular people and not be the voice of God from the mountaintop," recalls longtime NPR Congressional correspondent and "All Things Considered" co-host Linda Wertheimer (1989-2002), 78, one of the first people hired by the network in 1971.

Stamberg recalls: "Bill said the most valuable words maybe anyone ever said to me in my life: 'Be yourself.' Who in the world says that except Mr. Rogers? It was an enormous permission."

Siemering, a founding father of NPR, created a special place for women at the network, especially the quartet of "Founding Mothers" — a term coined by Stamberg, now a special correspondent for NPR's "Morning Edition." The remainder of that quartet with Stamberg and Wertheimer: Nina Totenberg, 77, and the late Cokie Roberts.

The 'Founding Mothers' of NPR

In her new book, "susan, linda, nina & cokie: The Extraordinary Story of the Founding Mothers of NPR," Lisa Napoli writes: "Some women in the 1970s marched for equality, or sat on the sidelines angrily lamenting the lack of it. Susan, Linda, Nina and Cokie had, through a combination of will, timing and talent, used their distinctive perches to elevate the status of their sex in a different way — working a hundred times harder than men while wielding microphones, as Stamberg described them, as 'magic wands waved against silence.'"

With a print background and awards for her Supreme Court coverage, Totenberg — NPR's longtime legal affairs correspondent — was recruited by the network in 1975. But like many women of her generation hoping to get into journalism, Totenberg had confronted male editors in her early job searches who would say a variation of "Oh, we don't hire women" or sent women applicants to fairly menial jobs.

"NPR was willing to hire us [as on-air journalists] for almost no money," Totenberg told me. "That's why we had such a stellar cast of women. Because no men would work for the money we made in the beginning."

"NPR was willing to hire us [as on-air journalists] for almost no money."

Asked years later by journalist Claudia Dreifus (and cited in the Napoli book): "How do you feel when you meet younger women in journalism who haven't any idea how rough things used to be for women in the 'bad old days?'" Totenberg offered this glib response: "Murder comes to mind."

In the fall of 1977, Totenberg received a resumé from Roberts, who'd worked for CBS Radio in Greece when her husband Steve, a New York Times reporter was based there. Because Roberts was the daughter of then Louisiana Democratic Rep. Lindy Boggs and the late House Majority Leader Hale Boggs, there were objections at NPR to hiring her full-time.

Roberts got a temporary position, but it didn't take long for her to display her intimate knowledge of Congress and Washington. She became a pillar of the NPR reporting staff in 1978, covering issues not getting wide exposure in the media: education, welfare and parental leave.

Trailblazers Stamberg, Totenberg, Wertheimer and Roberts

"It was a really wonderful moment in time, that these four women were trailblazers," says Napoli. "It just seems from the minute they met, these women saw in the other women what they might have felt was missing."

One thing they clearly shared was the keen ability to break into the Old Boy's Club and be taken seriously as journalists.

When Wertheimer was barely a teenager, watching television at home in Carlsbad, N.M. in the mid-1950s, she saw NBC's Pauline Frederick standing in front of the United Nations, reporting on the invasion of Hungary. Wertheimer told me: "I pointed to her and said to my mother, 'That's a woman!' and my mother said, 'Very good.' I had always admired [Edward R.] Murrow when we listened to him on the radio and always wanted to do that kind of work. Until I saw Frederick on TV, I never had any idea women could."

Roberts kept one foot at NPR when jumping to ABC News in 1988. She had a rare mix of self-effacing humor and a connection to anyone who's anyone in Washington. (A legendary 1990 Spy magazine cartoon titled "Moderately Well-Known Broadcast Journalist or Center of the Universe?" diagrammed her as the hub of connections to the famous and powerful.)

Roberts was also a mentor to many women at NPR and ABC News. As a former "Nightline" colleague of mine, Madhulika Sikka, put it after Roberts died of breast cancer in 2019, "She was our behind-the-scenes whisperer...she had our backs."

Stamberg Celebrates 50 Years at NPR

While "The Most Trusted Man in America," Walter Cronkite, was forced out of the CBS anchor chair at the mandatory retirement age of 65 in 1981, times have changed. On April 5, Stamberg tweeted: "Today is my 50th anniversary at NPR. Hard to believe. Only our grandfathers spent that much time at the same workplace. Now a Founding Mother has!"

Neither Stamberg nor Totenberg have plans to retire. Wertheimer, now Senior Correspondent/Host for NPR, plans to travel to stations as an NPR ambassador when the pandemic is over.

Totenberg says that although NPR may be an exception, "broadcasting in general is a pretty ageist world. It's probably in some ways more ageist than sexist."

Last year, just before the pandemic shut down life as we knew it, a star bearing Stamberg's name was unveiled on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Last year, just before the pandemic shut down life as we knew it, a star bearing Stamberg's name was unveiled on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Humbly, Stamberg said the honor really belonged to NPR, now attracting 60 million listeners a week on multiple platforms.

The "Founding Mothers" of NPR, along with thousands of others in public radio, give the lie each day to comedian Fred Allen's quip that "radio is as lasting as a butterfly's cough." Concluding her Walk of Fame remarks, Stamberg observed, "Now there's a star on Hollywood Boulevard to prove it."

Over the past half century, NPR has become instantly recognizable by its voices and the way it exploits the intimacy of the medium. One memorable example: taking listeners into a pitch-black closet where science reporter Ira Flatow brought Stamberg to demonstrate how Wint-O-Green Life Savers spark in the dark when you bite them.

Stamberg's mother heard the story, prompting her to phone her daughter and ask: "Susan, going into a closet with a young man, what were you thinking?"