How to Have Fun with Your (Perhaps Difficult) Aging Parent

Advice to adult children who find it hard to cope

Back in the 1970s, when Christina Britton Conroy was just 27, her mother died. In an instant, the aspiring singer and actress became principal caregiver for her temperamental, self-absorbed, 81-year-old father, a man with whom she’d never had a close relationship. Over the next few years, she tried in vain to keep him safe and happy while developing her career.

Then she had an inspiration.

Since her dad (a psychologist who had studied under Karl Jung) liked nothing more than to talk about himself, she bought him a portable tape recorder and a pile of blank tapes. Whenever she would visit his New York apartment, she would have him record stories from his life while she painted watercolors nearby.

“I could do what I needed to do while he was doing something that he enjoyed,” she says. “I wasn’t wasting time for myself, and he was feeling good about himself.”

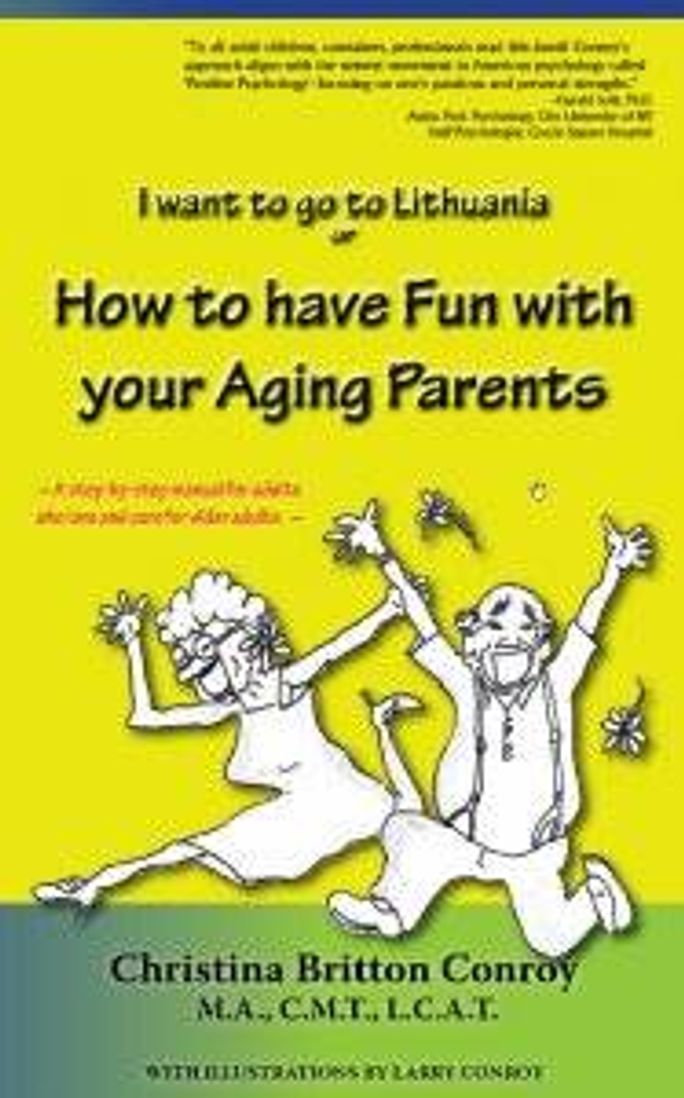

That positive experience helped inspire Conroy’s eventual decision to become both a music and creative arts therapist. (She now works with children and homebound older adults in New York.) It also inspired her book, How to Have Fun with Your Aging Parents (Black Lyon Publishing, 2017).

Easy as 1-2-3?

The promise in the book’s title might seem improbable, but Conroy argues that adult children of elderly parents can find peace, even joy, in difficult situations. All it takes is patience, imagination and a three-step process Conroy outlines.

Step 1 is to determine your parent’s personality type; for dysfunctional parents, the options she offers are “stuck in a rut,” “self-isolating,” “dangerously independent” and “unreasonably demanding.”

Step 2 is to figure out your relationship to your parent. As was true in Conroy’s case, this could involve unpacking some emotional baggage.

Step 3 is to discover and unlock your parent’s passions, which could go far beyond dictating old stories.

Throughout the slim volume, Conroy describes older adults she has worked with, many at an East Harlem neighborhood senior center during the 1990s. Their stories serve as powerful examples of what happens when someone rediscovers a lost passion — or discovers for the first time a reason for living.

Rekindling Old Passions

Bill* is a good example. A child victim of polio, he had been sent to a special school where he learned to grind eyeglasses and make costume jewelry.

At the senior center, Bill signed up for one of Conroy’s music classes. After more than a year, he had developed so much self-esteem (if not musical ability) that he told her he wanted to offer a jewelry-making class. Within two years, he was teaching two classes a week to 40 or so students.

“He was strict, and he was good,” Conroy says. “He said for every two pieces of jewelry that a student made for themselves, the third piece they had to donate to the center to be sold.”

Proceeds from those sales and from other activities went into a fund that center members controlled. Among them was Peg*, who had a reputation for being angry, demanding and irrational.

Peg had been a pool shark in her day, and she wanted to spend some of the money on a pool table for the center. “The administration didn’t like the idea,” Conroy says. “I guess they thought it would bring in the wrong kind of people.”

Fortunately, Peg prevailed. “When she got her pool table, it ended up bringing in exactly the right kind of people, because it brought in the kids from the neighborhood, who would interact with the seniors and have pool tournaments,” Conroy says. “Peg ended up being the queen of the roost; she was setting up tournaments and suddenly had a reason to live.”

Finding New Interests

While Bill and Peg renewed old passions, Sam*, a retired welder, discovered a passion he didn’t know he had. “His life had been going to the shop, coming home, drinking beer and falling asleep in front of the TV,” Conroy says. “He liked his life; he liked being self-isolating.”

Arthritis robbed Sam of his trade, and a move to a nursing home robbed him of his privacy. Not surprisingly, he was constantly angry and frequently verbally abusive to those caring for him.

He did sign up for one of Conroy’s music classes, however. “I eventually figured out that for all those 30 years alone in his welding shop he’d had the radio on,” she says. “He was an encyclopedia of pop music from the '30s and the '40s and the '50s. He knew every band, every singer.”

Armed with that insight, Conroy convinced Sam to start a music-reminiscing program for the other residents. He felt strong and important and gradually became interested in other people. “I’m not going to say it made him into a nice guy, but it made him into a nicer guy,” Conroy says.

Can you achieve similar results with your aging parent? Conroy thinks so. “Try to have fun,” she says. “Try to laugh at craziness — because there is so much craziness.”

* Conroy uses pseudonyms in the book to protect privacy.