What to Do About Hate in America

Reflections on the Pittsburgh massacre, pipe bombs and Matthew Shepard

Political hate. Religious hate. Racial hate. Gay hate.

The past few days have laid bare what few of us like to acknowledge. For all the bounty and blessings of living in this country — and there are many — there is also a river of hate that runs through the land.

No longer just a stream, what we’re witnessing is a raging river of animosity toward the other — the other political party, the other race or ethnic group, the other religion, the other sexual orientation.

The Demonization of 'The Other'

What were once private conversations between like-minded bigots are now hidden in plain sight, playing out every day on social media, on talk radio and on cable TV shout fests. It’s the demonization of "the other."

Blessedly, not all of the spewed hate explodes into violence. But a snapshot of a few days last week in this country should set off alarms.

Just ask the families of two African-Americans shot and killed Wednesday at a Kentucky Kroger by a man reportedly with a history of making racial threats.

Or ask the families of 11 worshipers killed in Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue on the Jewish sabbath Saturday, the worst single attack on Jews in U.S. history. Even more chilling: it was just one of nearly 300 mass shootings in this country in 2018 alone. That’s the equivalent of nearly one per day, according to the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive. (Next Avenue offered advice on coping with grief after that tragedy.)

Or you can ask Dennis and Judy Shepard, who between these hate crimes were interring the ashes of their 21-year-old gay son, Matthew, at the Washington National Cathedral on Friday morning.

Twenty years earlier in a crime so horrific that hate crime legislation was named for him, Matthew Shepard was robbed, pistol whipped and left for dead on a Laramie, Wyo. fence. He was so disfigured, a bicyclist who found him thought, at first, he was looking at a scarecrow. It’s bad enough the Shepards lost their son in this unspeakable way, but days later they had to contend with protestors from the Westboro Baptist Church who picketed the funeral with vile signs, including “AIDS cure fags.”

Fearing that any public final resting place would be open to desecration, the Shepards held onto their son’s remains for two decades until they could find a venue they thought would be appropriate and safe. Given the family’s ties to the Episcopal Church, the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. made sense.

“We were worried about the haters out there and vandalism,” Dennis Shepard told the television program Matter of Fact. “And a lot of people go to Washington, D.C., so it allows them to visit Matt at the [National] Cathedral.”

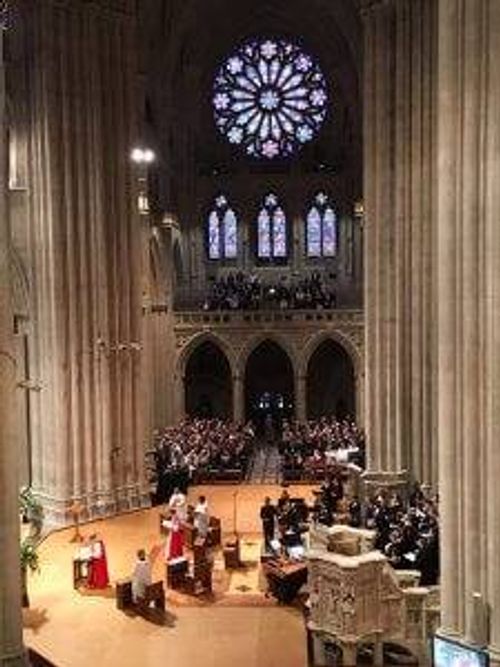

The Mathew Shepard Service at the National Cathedral

I attended the National Cathedral service for Matthew Shepard, watching from the balcony. As the music swelled and the voices of the Gay Men’s Chorus filled the Cathedral, the Reverend Gene Robinson (the country’s first openly gay Episcopal bishop) carried Matthew’s ashes down the aisle in a candle-lit procession. I couldn’t help but think of the ongoing hate crime of that moment, as law enforcement professionals frantically searched for the person or people who’d sent more than a dozen pipe bomb packages to prominent Democrats and CNN.

In his homily, Rev. Robinson almost foreshadowed the awful events that would unfold 24 hours later and some 250 miles northwest of Washington. “The bigger picture here is what human beings tend to do, which is to label someone different from ourselves as ‘the other’ which is code for ‘not really human’ and then you can do anything to them that you like,” he said.

The Pittsburgh Synagogue Massacre

By Saturday morning at a meeting I attended at a bucolic retreat in upstate New York, I was ready to take a break from the realities of the troubled world. But apparently my phone wasn’t, when The New York Times notification popped up: A mass shooting was underway at a Pittsburgh synagogue. I shared the news with two others on either side of me, also Jewish.

It didn’t take long to reveal the full scope of the carnage. As a lifelong friend, David Shribman, executive editor of The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote to his readers, “Now we know it can happen here, and that here is anywhere.” Part of the dread, Shribman added, was “that our country, our city, our neighborhood (which was, in fact, Mr. Rogers’ actual neighborhood), our lives have come to this, and that this has come home.”

Angry Rhetoric and Painful Statistics

Some critics have drawn a straight line from the President’s rhetoric and tweets to the synagogue and pipe bomb hate crimes. But how can any of us know the trigger point for a twisted mind? This much I do know: In Mr. Trump’s divisive language, the journalists I’ve worked with for 40-odd years are not “the enemy of the people.” Many have risked their lives, indeed some have given their lives, to better inform their fellow citizens. Why the President continues to denounce the media as “fake news” and “enemy of the people” is something only he can explain.

Twenty years after Matthew Shepard became the public face of anti-gay hate crime and a few days after his remains arrived at their final resting place, Dennis and Judy Shepard are not about to rest. There they were Monday at a law enforcement roundtable at the Justice Department, pushing for greater protection for LGBTQ hate crime victims.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics data tells the story: 54 percent of violent hate crimes between 2011 and 2015 went unreported. Dennis Shepard explained why: “When you can still be fired for being LGBTQ in 30 states, why are they going to report?”

What the Shepard Family Is Doing

Hearing the news of the carnage at the Pittsburgh synagogue, the Shepards understood perhaps more than others the searing pain of loss from a hate crime. So even before they made their pitch at the Justice Department for more protection for hate crime victims, they began by offering their sympathy and condolences to the Jewish families in Pittsburgh who’ve begun burying their loved ones.

The Shepards said they know how it feels to lose someone you love — to hate. Sadly, in a country that is too often disparaging of “the other,” so do countless other families.

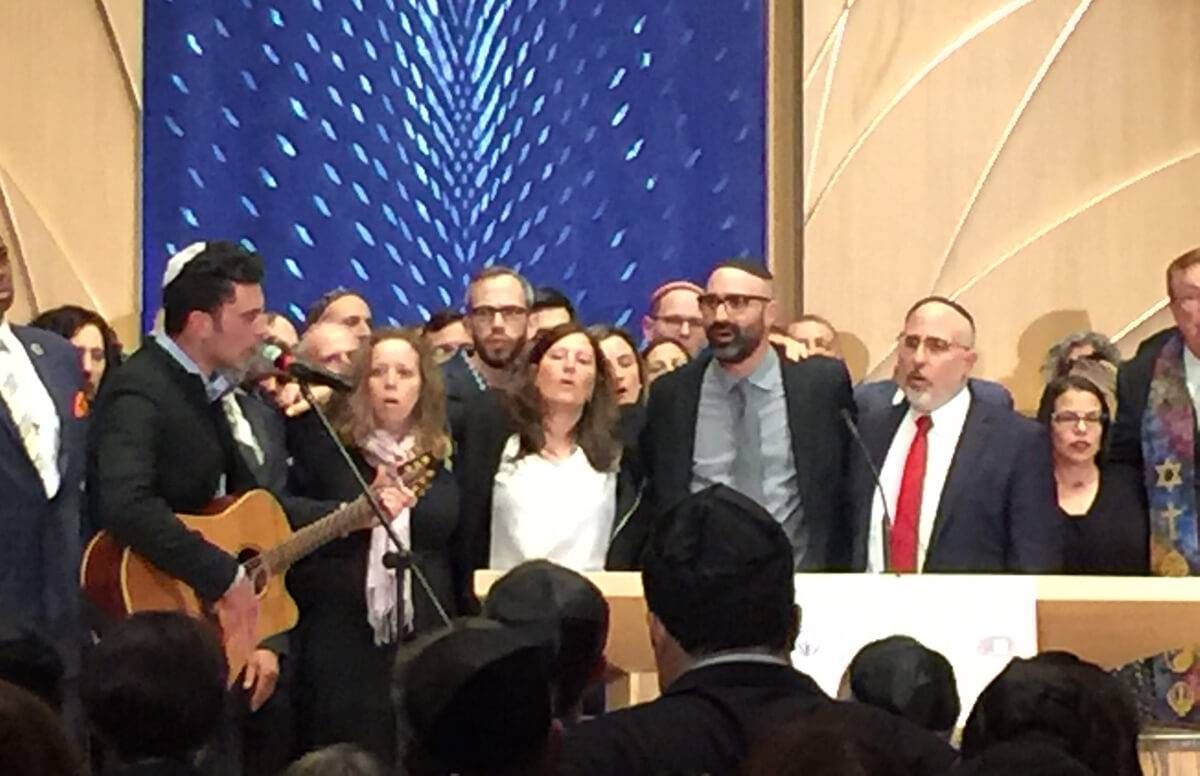

At an interfaith service I attended in Washington, D.C., Monday night, the dark cloud of the past week lifted slightly, when scores of clergy from different religions (Hindu, Mormon, Catholic, Muslim and many others) joined Rabbis, Jewish leaders, Governors and other elected officials to denounce hate and anti-Semitism.

What We All Must Do

Ron Halber, executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Washington, asked the question all of us are asking: “What is happening in our America?”

He went on: “The anti-Semitic, racism and bigotry have become normalized. Combine that with the accessibility of social media, mental illness, available weaponry and now you have a toxic brew that will culminate in violence.”

Halber wasn’t content with handwringing, though. He said the most important thing we can do to reverse the uptick in hate crimes is a “change in our national discourse.” That prompted sustained applause.

But he wasn’t done. “Something has become rotten in America’s moral fiber in our society,” he bellowed, “and we must and we will take America back.”