How Do Fairy Tales Tell Stories of Aging?

A new book looks at how characters like Hansel and Gretel can help us examine the chapters of our lives

Several years ago, three close friends, now in their 70s, decided to explore their thoughts and feelings about growing older by diving into the world of fairy tales.

What would they learn by revisiting stories of their childhood and reinterpreting them from a very different perspective, they wondered.

William L. Randall and W. Andrew Achenbaum, who spent long careers studying aging, wanted the freedom to write personally and reflectively, not academically.

Randall, a retired professor of gerontology at St. Thomas University in New Brunswick, Canada, has specialized in studying how the stories people tell about their lives shape their experiences of growing older. Achenbaum, a historian who spent most of his career at the University of Michigan and the University of Houston, has focused on the history of aging in the United States.

"The adventure that awaits us in the second half of life is that of exploring and owning our inner worlds" and reexamining fairy tales is a meaningful way to do this.

Their collaborator, Barbara Lewis, a retired psychoanalyst, Episcopal priest, and Achenbaum's wife, is especially interested in how people address the spiritual dimensions of aging.

Together, the three have published an imaginative, thought-provoking new book, Fairy Tale Wisdom: Stories for the Second Half of Life. In it, they examine tales such as The Tortoise and the Hare, Little Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, Hansel and Gretel, The Ugly Duckling, and several religious-oriented stories.

Which characters do I identify with and has this changed from when I was a child, they ask themselves. What personal memories do these stories evoke, and what sense do I make of these experiences now that I'm older? What images of aging are embedded in these stories, and how do I relate to that?

Reexamining Fairy Tales Today

"The adventure that awaits us in the second half of life is that of exploring and owning our inner worlds" and reexamining fairy tales is a meaningful way to do this, Randall told me in a phone conversation.

For him, the exercise has been transformative. Previously, Randall said, he conceived of "life review" – a form of self-reflection important to many older adults – in a chronological framework.

"You go over the past and take stock of key events and turning points in your life and hopefully come to some sort of positive assessment along the lines of 'I did best with the circumstances I was given,'" he explained.

While writing this book, Randall said, he also came to recognize the value of reviewing emotion-laden images and moments that bring to light important themes. An example: in his chapter on Jack and the Beanstalk, Randall ends up associating the fearsome giant with his often-critical father, who he described as having a "monstrous side" that "I hated and feared."

For Randall, one of the key tasks of growing up was cutting his father down to size and asserting his independence. (Think of Jack cutting down the beanstalk.) His father's aging advanced those tasks: beset by the pain of arthritis, the old man became more appreciative of his son and reconciliation of sorts occurred.

Writing about the tale, Randall said he realized "age cuts us all down to size." Also, all kinds of authorities lose their power over us (as the giant lost power over Jack) as we move into a new stage of life with different priorities.

A New Lesson from the Tortoise and the Hare

Lewis examines shifting priorities in her take on the Tortoise and the Hare. (All three authors riff on this story at the beginning of the book.) A conventional interpretation might be that the hare, who stops to take a nap during the race and ends up losing, is foolish while the Tortoise is steady, reliable and admirable.

But Lewis questions the underlying premise of the story from an older person's perspective. "Is life to be seen as a competition? As something we should try to win?," she writes. Especially as we grow older, she observes, a "zero-sum view of the meaning of life" might not be useful.

This leads Lewis to empathize with the hare who, she writes, "can no longer bear to put her energy into the race. She knows she can win; there is no challenge left in this arena. She has run the race, or others like it, long enough." How many people share similar feelings upon retirement?

Achenbaum, who describes his youthful self as an unathletic "plodder" – in other words, a tortoise — writes of learning how to compete with others as an adult, "to be a hare." Why was it so important for him to reject his tortoise nature in his early and middle adulthood, he asks. Is it possible that he's both a tortoise and a hare, and that the dichotomy between the two is false?

"We, like Hansel and Gretel, have survived. We were able to surmount difficulties – maybe even near-fatal experiences – and, even if scarred, lived through danger and frailty."

With age, we tend to move away from dualistic thinking and better appreciate paradoxes, the authors observe at various points in the book. Also, we realize that our own stories are, by necessity, incomplete until the very end, and we come to accept that.

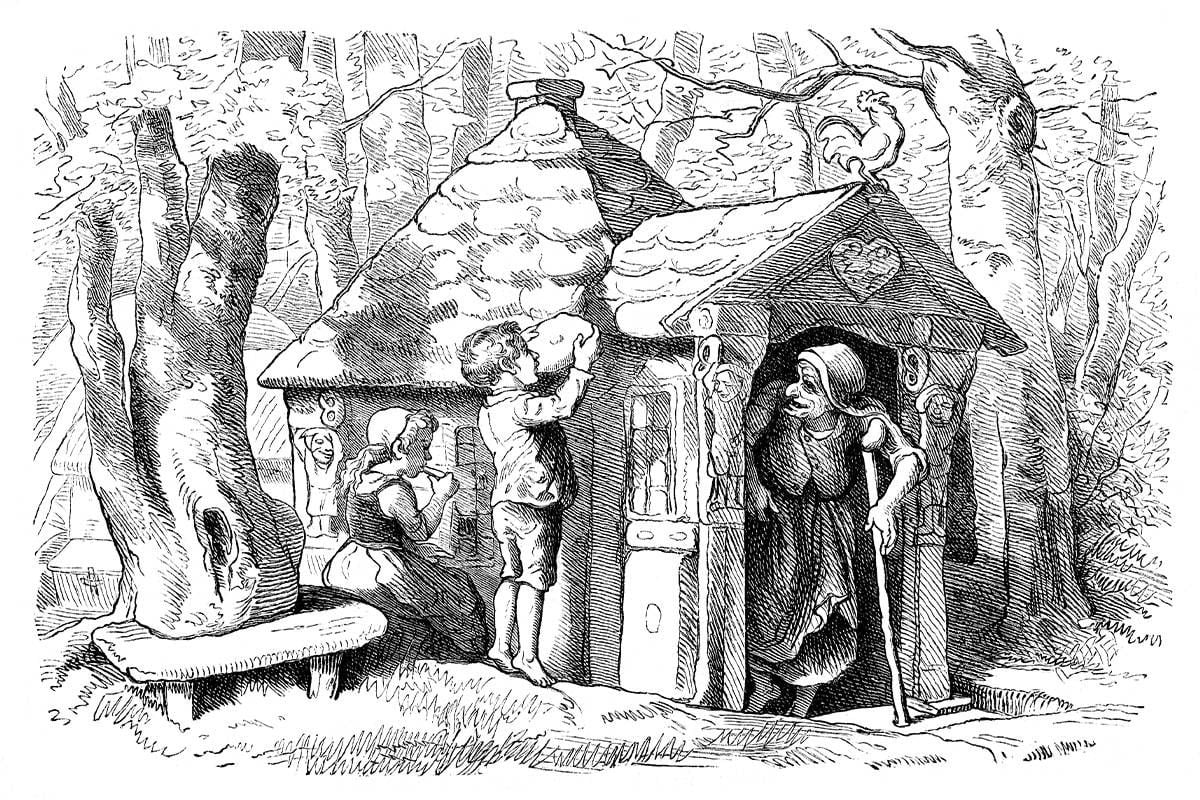

Hansel, Gretel and the Challenges of Aging

Of the stories she reviewed, Hansel and Gretel was particularly resonant for Lewis. Rereading this tale from the perspective of an older adult helped her understand that "we, like Hansel and Gretel, have survived. We were able to surmount difficulties – maybe even near-fatal experiences – and, even if scarred, lived through danger and frailty."

In Lewis' interpretation, the witch who threatens Hansel and Gretel is a symbol of the "uncaring, often cruel world that lures us by promising wonderful treats." And Hansel and Gretel's expulsion from home by an evil stepmother evokes the challenges of aging.

"As we age, many of us feel the shock of being 'thrown out' of our adults lives – by deaths of loved ones, by our own illnesses, by the leaving of grown children, or by retirement," she writes.

If we're lucky, we find a new path forward. Achenbaum said that happened to him in writing this book. "It was really a turning point in my retirement," he told me. "I didn't have to worry about peer review, deadlines, tenure decisions. I could write the way I wanted to write for myself, and that is really spiritual."