How to 'Bee' a Good Gardener

Making changes in your yard (including more native plants and a smaller lawn) will give bees a boost

I've loved the act of gardening my entire life but what that means has certainly evolved over time. As a child, I had my own rock garden (mostly rocks, to be fair) but I also remember how thrilling it was to watch hyacinth roots pushing through the gravel in a see-through jar on our winter windowsill.

"The pressure on solitary bees and other native pollinators is immense."

With my first home came my first adult garden but there was no long-term vision; in fact, the only "planning" occurred when I excitedly unloaded my colorful purchases and decided where to put them. This methodology did not serve me well, especially since I would routinely forget to water them, only to be surprised one day by a crumbling green powder where that Himalayan Poppy used to be.

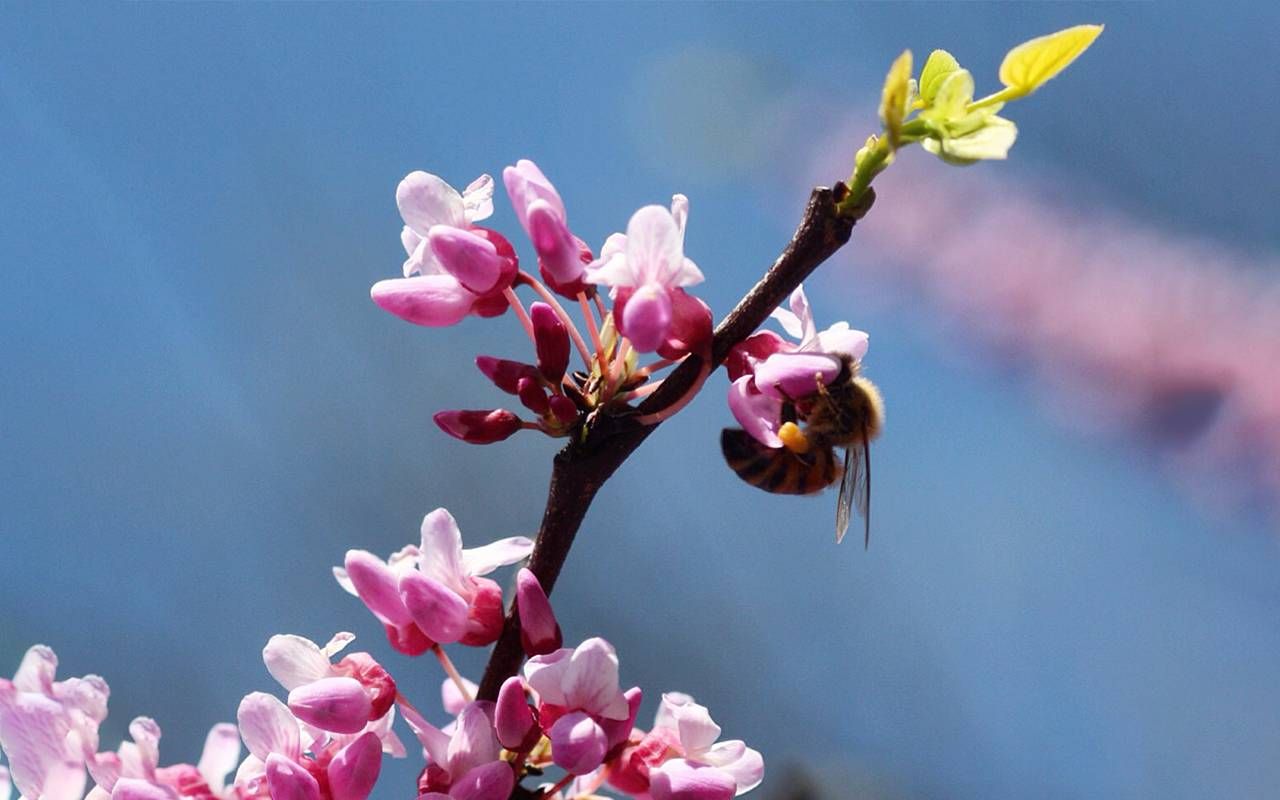

When my children were young, I ambitiously dug out a vegetable patch and we all delighted in the visiting toads and fat bumblebees that lowered themselves into squash flowers. But then the weeds came (as did the earwigs) and soon the little bed was a tangled mess. By mid-July, at the end of an exhausting day, an icy gin and tonic would prove much more seductive than kneeling pad and secateurs.

But as I grew older, my interest in the garden expanded beyond simple maintenance. I began to re-see all the things I'd originally fallen in love with: the appearance of different birds at different times of day, the lovely water striders, Mariachi-influenced "peepers" in our pond and jellied necklaces of toad eggs that were suddenly festooned amongst the water lilies. I also joined a local Master Gardeners' Group online and surrounded myself with gardening books over long dark winters.

The Pressure on Bees

But some of the reading was unsettling. Most people are familiar with the current decline in honeybees and the devastation this implies, but, in fact, there are nearly 4000 species of our own "native" bees that are in trouble too. I had not previously understood that honeybees are not native to North America at all — they were brought over by the first colonists as well as the Old World crop plants that these bees would pollinate.

Longtime beekeeper and producer of award-winning Canadian honey, Mike Wood, who lives in Union, Ontario, Canada, shares his own concerns.

"Honeybees are a managed 'herd,' so really, they'll probably be okay in the medium-term," he explains. "But the pressure on solitary bees and other native pollinators is immense. And unfortunately, that pressure is only made worse for them by ... keeping honeybees," says Wood.

According to Wood, increasing the density of honeybees in a meadow "adds hard-working competition for those little native and solitary bees, and it also has the effect of introducing disease and parasite pressure — which honeybees may wind up getting medicated for because again, they're being managed."

All bees need a food source that is available throughout the season, not just something that flowers for a week or so at the beginning of spring, so an ongoing, rotating selection of suitable plant choice is essential. It was a crushing loss for me as a gardener to learn that an estimated 80% of ornamental plants currently being sold originated in Asia or Europe and consequently, are not the ideal fit for North American biodiversity, especially since our 'specialist' bees can only eat pollen from certain plants.

Determining which plants are native and where to find them may seem complicated but it needn't be; in fact, I was able to compile a basic list (and learn that birds, butterflies and other animals would benefit hugely) in much less time than I usually waste searching Netflix.

Also, it is astounding how much work has already been done to streamline the process on sites such as Audubon and National Wildlife Federation. Many nurseries are now carrying native plants but if you don't see any, be sure to ask to help create the demand.

Douglas W. Tallamy, a professor in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware and bestselling author of "Bringing Nature Home" and "Nature's Best Hope" notes that "in the past, we have asked one thing of our gardens: that they be pretty. Now they have to support life, sequester carbon, feed pollinators and manage water."

What You Can Do in Your Yard

Tallamy has also co-founded Homegrown National Park, a grassroots project which challenges private property owners to "shrink" their lawns, remove invasive plants (which means removing plants that have been proven to be invasive, not every plant in your garden that is not native to the region) and choose native plants.

Fall is a traditional time for clean-up, but it's also a critical time for bees who are scoping out good places to spend the winter.

An interactive map documents the program's success by zip code and the ultimate goal is twenty million acres of native plantings in the U.S., which amounts to approximately half of the currently mowed green lawns.

The best thing about Tallamy's ideas is that they are doable. Although some people may balk at the concept of total lawn elimination, even tiny changes such as becoming more mindful of plant selection or filling window boxes with native flowers will have an impact.

In "Nature's Best Hope," Tallamy observes that "knowledge generates interest and interest generates compassion." Incidentally, I removed my own front lawn about 15 years ago — amidst curious stares from the neighbors — but it's now full of bright swaying color and has honestly never looked like the haunted house on the street.

Fall is a traditional time for clean-up but it's also a critical time for bees who are scoping out good places to spend the winter. Avoid deadheading and cutting back thicker stems (like sunflowers) since tiny bees may already be nesting inside. And in the spring, hold back a bit for the same reasons.

Move logs or fallen limbs to a back corner of the yard for bees who prefer to nest in soft wood, and don't rake leaves unless absolutely necessary since the leaves will break down into a nutritious blanket for the soil as well as hosting a thriving eco-community beneath. Tallamy also points out that if you allow deep pockets of leaves to remain under your trees it will help to destroy the grass and you'll be creating some instant garden beds for the spring.

4 Gardening and Bee Resources

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension: Garden & Yard