Why Addressing Infection Control in Nursing Homes Is More Important Than Ever

How learning from the past can help long-term care facilities prepare for future pandemics

COVID-19 took an extraordinary toll on nursing home residents and staff since the pandemic started more than a year ago. Age, multiple underlying health conditions and communal living resulted in more than 671,000 cases and 134,000 deaths to date.

And lockdowns prevented family, friends and ombudsman from visiting — sometimes for as long as a year.

The virus' toll on nursing home workers themselves (many of whom working multiple jobs to make ends meet) was also steep, with over 608,000 cases and nearly 2,000 deaths.

"It was shocking how long it was taking in order for proper infection control to actually be put into effect in some facilities. It was very concerning."

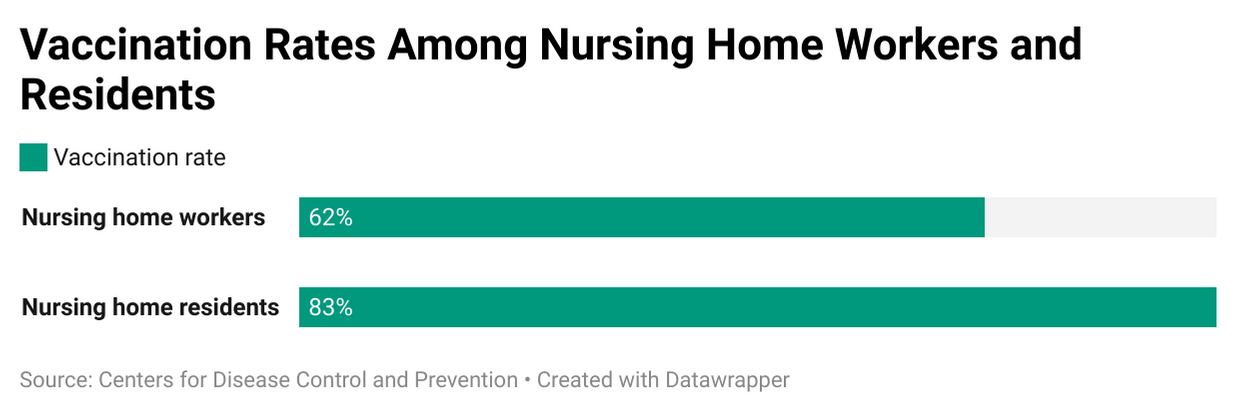

The nature of their work made them likely transmitters of SarsCoV2 within facilities. Nationally, 83% of nursing home residents have been vaccinated against COVID-19, but only 62% of the 1.6 million workers in these facilities are fully vaccinated so far.

Which means serious concerns about infection persist, especially as cases of the highly transmissible Delta variant climb throughout the U.S.

What lessons did we learn from 2020 and how can we ensure that long-term care residents — and those who care for them — stay safe?

Experts say that unless infection control and training changes, and quickly, more residents and staff will likely get sick or die.

A Patchwork of Problems

"There have been some longstanding systemic problems in nursing homes and other long term care facilities that have not been adequately enforced, and we think that's a big reason why facilities weren't better prepared," said Lori Smetanka, executive director at the advocacy group The National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care. "Infection control was the number one deficiency cited prior to the pandemic, so we knew there needed to be better attention paid to ensuring prevention practices were being employed and staff are properly trained."

Issues with infection prevention and staff training are really symptoms of a larger problem, according to Janine Finck-Boyle, vice president of regulatory affairs for Leading Age, which represents more than 5,000 nonprofit aging services providers.

A patchwork approach of assistance from the federal government left many nursing home operators scrambling to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing and to hire additional workers.

"Nursing homes have always had to have an infection control plan. The virus showed flaws all over the country, not just in nursing homes, in taking care of older adults," Finck-Boyle said.

Nursing homes have been working with infection issues for a long time, including MRSA, C-diff, flu and pneumonia, noted Traci Harrison, a nurse researcher at University of Texas, Austin who focuses on the nursing home environment and its impact on residents.

"They know the protocols and how to document something that could be airborne. But they may not have been trained as well in pandemic approaches, which is a more acute care type of training," she explained.

Predictably Unpredictable

During other serious health outbreaks, most people are cared for in a hospital and discharged home after recovering. This time, some COVID-19 patients were sent to nursing homes to continue their recovery and to free up hospital beds.

But many nursing homes were not adequately prepared for these sicker patients — from setting up isolation floors to instructing staff on proper infection protocols for this novel virus.

"We have a whole contingent of what are being called temporary nurse aides who have very minimal training, as few as eight hours. Some are still not fully certified and trained."

In Texas, for instance, nursing homes with on-site nurse practitioners had fewer problems than those without full-time higher level nursing staff due to the additional infection training, according to Harrison.

"When you have trained as an RN for many years, infection control becomes part of who you are and what you do." She said it's simple: If you invest in a higher level of staff, you get a higher level of care.

But even six months into the crisis, Smetanka heard reports of staff going into residents' rooms without gowns, masks or gloves on. During a conference call with then Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Director Seema Verma, Smetanka said medical directors were imploring some facility staff to get their infection prevention practices under control.

"It was shocking how long it was taking in order for proper infection control to actually be put into effect in some facilities. It was very concerning," Smetanka said.

Many facilities were still struggling to obtain enough PPE, but that doesn't negate hand washing, she noted. "The biggest issue seemed to be inadequate staff training."

Staffing Shortages Exacerbate the Challenges

There was already a shortage of qualified staff in many locations and when the pandemic hit, large numbers of workers either got sick themselves or had to stay home due to family concerns. It affected the ability to train staff properly.

Additionally, some training requirements were waived at the start of the pandemic; aides did not have to be fully trained and certified within the required four months.

"We have a whole contingent of what are being called temporary nurse aides who have very minimal training, as few as eight hours," said Smetanka. "Some are still not fully certified and trained."

A CMS special commission has investigated the high rate of COVID-19 cases and deaths in nursing homes. The commission found "the pandemic's spread in these institutions has exposed and exacerbated long-standing, underlying challenges in this care setting."

The commission issued 27 recommendations and action steps, including having a better supply of PPE on hand, giving more respect, training and support to direct care workers and providing sufficient funding for quality nursing home operations, workforce performance and resident safety.

Hiring more staff isn't always easy, though. The median annual staff turnover in nursing homes is extremely high, about 94%. Replacing and training new workers is frequently challenging. More than 1 in 5 nursing homes reported staff shortages in 2020.

Having a steady workforce, paying a living wage and educating them on best practices are things most nursing home operators really strive for, according to Finck-Boyle. "We have to make workers feel valued; we want to be able to train them with an infection preventionist and keep that person," she said.

Will Vaccine Mandates Help?

One major roadblock to making nursing homes safer is the refusal of many of their workers to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Even if residents are vaccinated, breakthrough infections can occur, since Delta is highly transmissible. Nationally, the combined proportion of cases attributed to Delta is estimated at more than 99%, according to the CDC.

And while a majority of healthy, vaccinated people will only experience mild effects if they contract a breakthrough infection, that isn't always true for vaccinated nursing home residents, due to their weaker immune systems and underlying conditions.

While coronavirus cases are certainly not at a level seen at the peak in the fall of 2020, CDC data show COVID-19 cases and deaths creeping up among both residents and staff at nursing homes throughout the U.S.

President Joe Biden issued an emergency declaration on August 18, requiring vaccinations of staff at more than 15,000 Medicare- and Medicaid-participating nursing homes (that still omits thousands of assisted living facilities which are not regulated by CMS). Facilities that don't comply risk losing federal funding. But not every worker in them is willing to do so, for a variety of reasons.

"We have to go into secondary institutions like trade schools and high schools and help people see how this could be a good career."

Vaccine hesitancy is real and it takes one-on-one education to try and change attitudes.

"We need to do whatever we can to encourage people to do this voluntarily, make sure they can easily get the vaccine or give them support like paid time off," said Smetanka.

The current mandate is a good start, but it should extend to all health care workers, including hospital staff, home care workers and even EMTs, according to Kathleen Unroe, a research scientist at the Indiana University Center for Aging Research at Regenstrief Institute and nursing home physician.

"When it comes to infection control, it's really discordant to think about how we are going to protect the vulnerable patient who interacts with the health care system and all these different points, but we just selectively pick one. There is a lot of hands-on care that occurs as a patient moves through the continuum of care," said Unroe.

If nursing home workers are terminated or quit over the vaccine mandate, it will only add to existing staffing shortages. Some of these workers watched 25% of their residents die. Some lost fellow staff members.

"They were going through such chaos and grief that they never want to do it again. The amount of suffering that went on, and continues to go on, is unbelievable," said Harrison.

No Easy Answers

In addition to increasing vaccination rates, vigilance about testing workers and visitors, masking, social distancing and proper PPE protocols must remain high. Unroe said the facility she works in avoided an outbreak for eight months. But despite their precautions, Unroe learned a staffer recently tested positive for the Delta variant, which is rampant in her community.

Still, she said, "I feel safer in this environment than I do in a lot of public spaces."

The vaccine mandate is an important strategy, but not the only approach to improving infection control. Reducing worker turnover through better pay and a viable career path will also help.

The Biden administration recently announced a $2.1 billion investment to improve infection prevention and control activities across the U.S. public health and health care sectors. The funds will assist health care personnel to prevent infections more effectively; support rapid response to detect and contain infectious organisms; enhance laboratory capacity and engage in innovation targeted at combating infectious disease threats in places such as hospitals, nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The CDC will also partner with CMS to help state and territorial health departments train and deploy strike teams to help skilled nursing facilities, nursing homes, and other long-term care facilities with known or suspected COVID-19 outbreaks. The strike teams will allow jurisdictions to provide surge capacity to facilities for clinical services; address staffing shortages at facilities; and strengthen infection prevention and control (IPC) activities to prevent, detect, and contain outbreaks, including support for COVID-19 vaccine boosters.

As for staffing issues, it's smart to get young people thinking about a career in long-term care early on, according to Finck-Boyle. "We have to go into secondary institutions like trade schools and high schools and help people see how this could be a good career," she said.

"We can no longer not wash our hands. We can no longer not wear masks, as a regimented practice for everyone. This is a different time now, and we can't go back to where we were before."

Addressing the many systemic issues surrounding pay structures, long-term care financing and education programs is also critical.

"Medicaid reimbursement rates [from the federal government to nursing homes] need a boost, because without more money, they can't pay wages to be competitive," Finck-Boyle said. Medicaid is the primary payer for most long-term nursing home care.

Better training at all levels is also vital. "I don't think the average nurse who has never been in long-term care knows what it requires," said Harrison. "It makes transfers harder, it makes getting people to work in these settings harder." She thinks nursing schools should send students into these settings so they can learn about them first-hand.

Some nursing homes have put together incentive packages to lure nurses into long-term care and some states are looking into loan forgiveness for RNs. But right now, they're mostly just putting out fires, not planning ahead, said Harrison.

Meanwhile, what can families do to help loved ones stay safe?

Ask Tough Questions

Ask plenty of questions, these experts recommended. They advise being vigilant about COVID-19 rates in your community. If you're looking for a nursing home, when you winnow the options down to three or four facilities, research them using CMS' nursing home compare data; look at infection control ratings over past few years.

Also, ask administrators what they're doing to protect residents now and about their infection control procedures and policies around any outbreaks. How will they keep your family member safe? What can you expect when it comes to visitation?

If you can, visit and see whether staff is masked, gloved and gowned when interacting with patients. Ask about the kind of training staff gets — not just the nursing assistants and aides, but dietary, housekeeping and social services as well, recommended Unroe.

And check resident and staff vaccination rates, suggested Harrison. Find out: What is the facility doing to encourage compliance? Will your loved one's roommate be vaccinated?

"We can no longer not wash our hands. We can no longer not wear masks, as a regimented practice for everyone," she said. "This is a different time now, and we can't go back to where we were before."

Nursing Home Resident Rights

Nursing home residents have certain rights and protections under the law. The nursing home must list and give all new residents a copy of these rights.

These resident rights include, but aren't limited to:

- The right to be treated with dignity and respect

- The right to be informed in writing about services and fees before you enter the nursing home

- The right to manage your own money or to choose someone else you trust to do this for you

- The right to privacy, and to keep and use your personal belongings and property as long as it doesn't interfere with the rights, health or safety of others

- The right to be informed about your medical condition and medications, and to see your own doctor; you also have the right to refuse medications and treatments

- The right to have a choice over your schedule (for example, when you get up and go to sleep), your activities and other preferences that are important to you

- The right to an environment more like a home that maximizes your comfort and provides you with assistance to be as independent as possible

Source: Medicare.gov

Editor’s note: This story is part of The Future of Elder Care, a Next Avenue initiative with support from The John A. Hartford Foundation.