The Extraordinary Life of Jacques d'Amboise

In our 50 years of friendship, the dancer has taught me the steps to a life well-lived

Editor’s note: We remember Jacques d'Amboise who died on May 2 at age 86. This story originally ran on Next Avenue in December, 2019.

On a chilly Monday in New York City, legendary dancer and choreographer Jacques d'Amboise and I meet in his cramped, book-strewn office at the National Dance Institute (NDI). We go back a long way.

In the early '70s, when the dance boom made household names of Rudy (Rudolf Nureyev) and Misha (Mikhail Baryshnikov), I was an aspiring ballerina in the New Jersey suburbs, rehearsing for a year-end performance. Suddenly, a tall figure strode down the auditorium aisle, leapt in the air, flew six feet across the footlights and landed squarely on the stage. That entrance was my first encounter with this remarkable man.

Jacques was towering and rugged, with a flashing grin and a shock of black hair, a gregarious guy with a New England accent. That day, like all others, he was gracious to everyone. A few years later, we met again, this time at New York City Ballet (NYCB) company class, where I was beginning my professional career.

Lessons From a Master

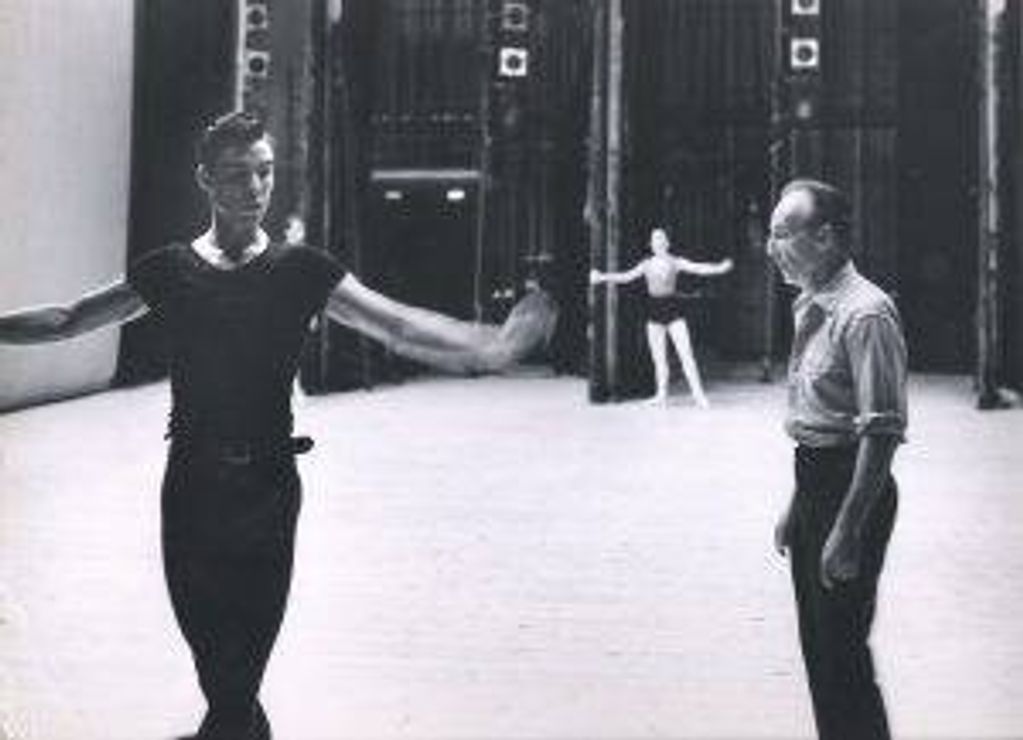

He pulled me aside, and in hushed tones tutored me in the intricacies of the sous-sus, a way of springing softly onto pointe, as NYCB founder George Balanchine preferred. It was just the first of many lessons over our near 50-year friendship — about living as an artist, what comes after the stage, surviving grief, the very meaning of life.

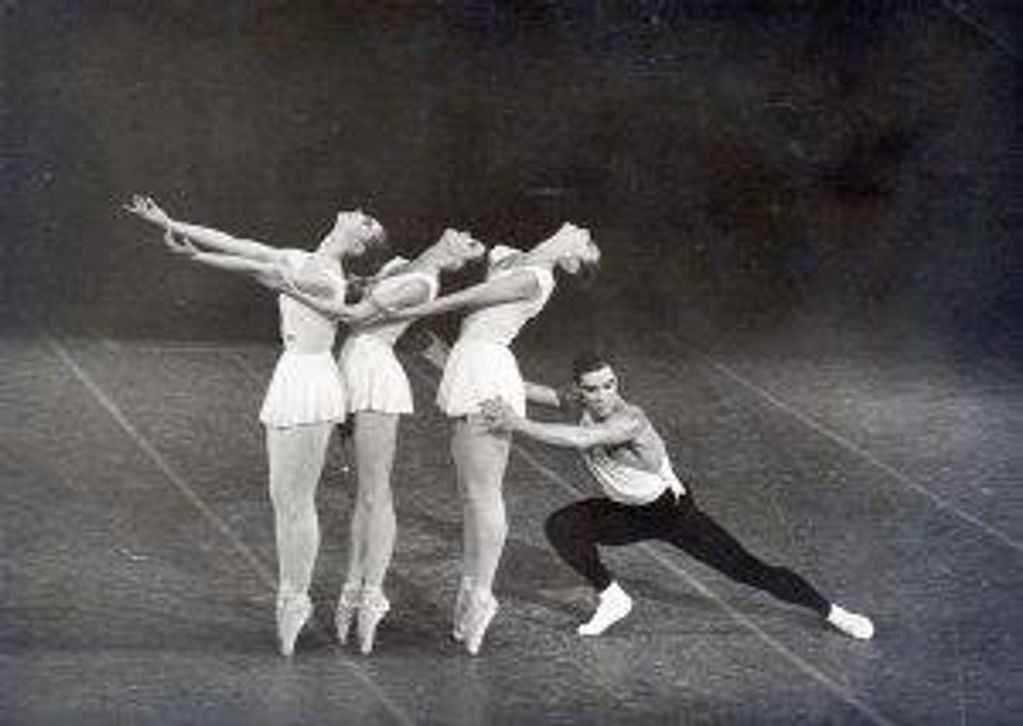

It's hard to overstate how big a star Jacques was in his prime. Not only a principal dancer known for his all-American athleticism, he also acted in movies and danced on Broadway. His signature role as a classical dancer, Apollo, was described by its creator Mr. B (our fond name for Balanchine) as "a wild untamed youth who gains nobility through the arts" — which reflected Jacques' own life story.

"The secret of making anything happen is to question it and edit it," he says. "And don't do everything at once. Do it step by step."

As a teenager, Jacques tells me, he ran with a bunch of street kids, "with gangs like West Side Story," he says. "They were ready to beat me up for being a ballet dancer." You've got the wrong idea, Jacques told them, and through a series of demonstrations and salesmanship that he would later use on children all over the world, he not only convinced the little gangsters to back off, but to come to the theater to see for themselves.

He would sneak his friends up the fire escape to the upper balcony. They didn't mind ogling all those beautiful ballerinas, and from the nosebleed seats, his "thugs," as he called them, would yell and whistle madly for their friend.

In his long career, Jacques, now 85, partnered with the most exquisite ballerinas of his time. He choreographed many works, including Irish Fantasy, which I danced many times under his watchful eye. He is the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, a Kennedy Center Honor, a National Medal of the Arts, as well as honorary doctorates from Julliard, Duke and 10 other universities. The documentary called He Makes Me Feel Like Dancin', about his work as a teacher, won an Oscar in 1983. But first and foremost, he considered himself a dancer.

An Extraordinary Second Act

A dancer lives two distinct lives: the first as a performer, the second, of necessity, an "encore career." The transition can be daunting.

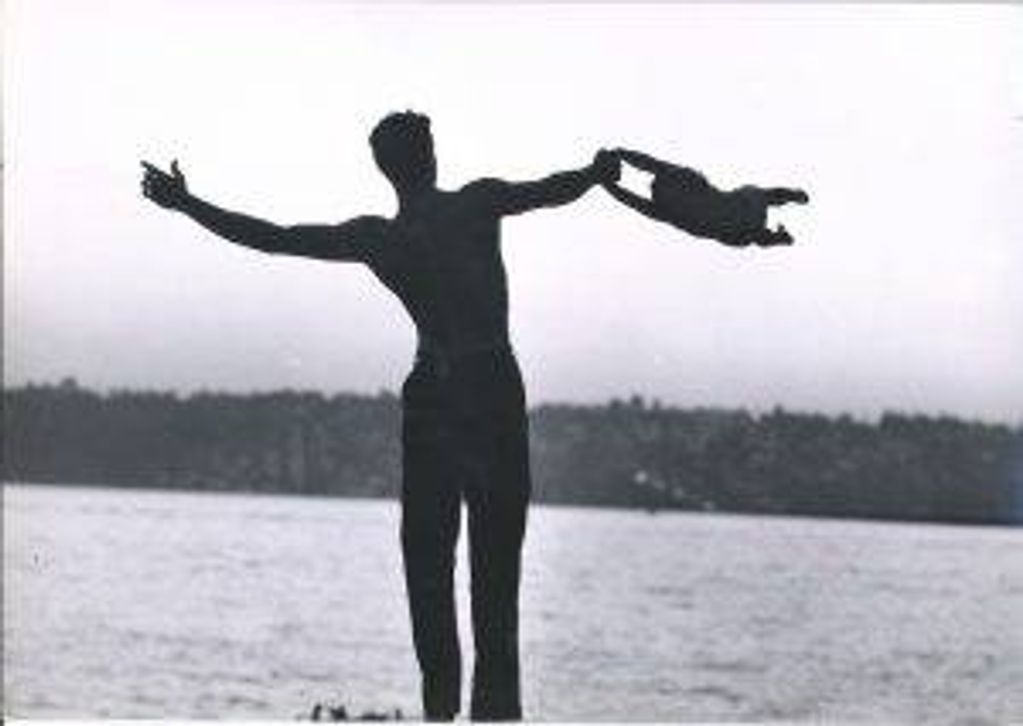

After nearly 35 years with the company, Jacques' final curtain call was a poignant farewell, no grand sendoff, as per his wishes. He tenderly lifted his ballerina, Suzanne Farrell, off the stage for the last time, and whispered the words, Here we go Mr. B, the last of the wine.

Jacques recalls that moment for me, noting that it was a tribute to his late mentor, Balanchine. "It's from a poem by Stephen Vincent Benet," Jacques says. "And he's saying it's the end of an era, the end of a time."

I will always remember the understated power of that performance and his graceful exit from the stage (which I tried to emulate when I retired 15 years later). But what proved more extraordinary would be Jacques' second act.

He did not choose to lead another ballet company, though it was offered. He did not go to Broadway or Hollywood. Instead, he stepped up his work as founder of NDI, a nonprofit that teaches inner-city kids to dance — two million to date, all over the world, all for free.

When I ask why he chose this direction, he answers as if it were obvious: "What a transformation it was for me as a street kid to have ballet and music. So, I thought I would introduce children to what it was like to be a dancer."

But Jacques' dreams grew even larger.

In 1994, he set out on a journey around the world, from the highest point of Nepal to the lowest near the Dead Sea, in search of young dancers. Like a pied piper, he led them to New York, where they joined 1,000 American kids for a grand convocation at Madison Square Garden.

Then, at 65, he fulfilled a lifelong dream to hike the length of the Appalachian Trail (2,200 miles) to raise money for his foundation. He paused occasionally to teach his Trail Dance (a quick jig) to park rangers, schoolchildren and even prisoners, asking them all to pass the dance steps forward.

The Importance of Now

How do you make these big dreams happen? I ask. "The secret of making anything happen is to question it and edit it," he says. "And don't do everything at once, do it step by step."

I mention Goethe's famous quote, "At the moment of commitment, the entire universe conspires to help you." He smiles in agreement.

"I decide to do something and then I tell everybody about it, 'cause when you shoot your mouth off, you've made a public statement — you're going to do this. Then you say to people, 'I need help. Who can join me? How can you help me?' And it's amazing how everybody will," he says.

Along with his successes, Jacques has suffered great losses. And, here too, he has been my inspiration.

His best friend and dear wife of 53 years, Carrie, passed away in 2009. It was his deep connection with people, as I saw firsthand, that helped him navigate onward. Even today, his crowded datebook, written in his spidery scrawl, looks like a Jackson Pollock of places, dates and contacts.

I ask him how he stays so engaged. "People are interesting and everybody has their own story and tragedy and joy and dreams. Everybody has dreams," he says. "You know, the best thing to do is hang around with young people. I like talking to them, find out what they're doing, what music they're listening to. Ask them questions. You know. . .'What did you eat for breakfast?' It's a great opener. Everybody loves to tell you!"

He strolls down the street, turns slightly back and reminds me, "Have joy in your life!"

Perhaps what I admire most about Jacques is not only the bond he has with the children he teaches, but the long-term friendships he so carefully maintains. In his presence, he is right there with you, completely in the moment.

Although he feels this is "just good manners," Jacques firmly believes that when you are with someone, you must "stop and listen."

He continues, "So each time you're with somebody, this is the most important person. Because it's the only thing you control — that one little second called now. Right now! We don't realize what an important word now is, this one second while we're still breathing and in control. I'm with you now. Five minutes from now I may not be here."

As the afternoon ends, we part and he moves off into the distance, onto his next adventure: recording a podcast that evening in front of a live audience. He strolls down the street, turns slightly back and reminds me, "Have joy in your life!"

And with that line he makes his exit, as graceful as I have come to expect from this remarkable man, my friend.