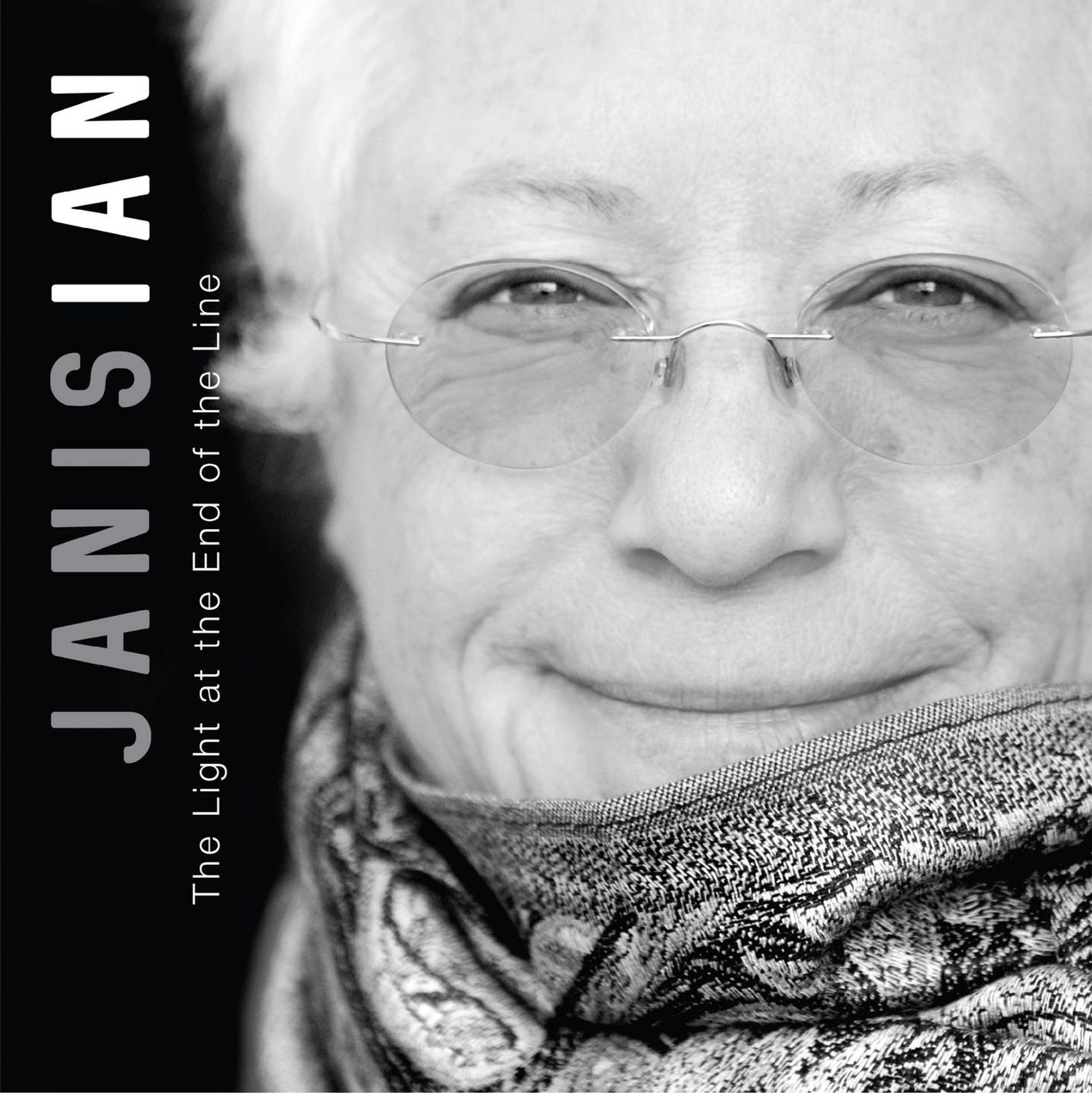

Janis Ian Sees The Light at the End of the Line

The Grammy Award-winning singer/songwriter discusses her latest — and final — solo studio album

Janis Ian was only 14 years old when she penned her first single, "Society's Child (Baby I've Been Thinking)." Though the song, released in 1966, became a hit, its commentary on interracial relationships was enormously controversial for the time and led to hate mail and death threats. But the backlash didn't stop Ian from releasing new music. In the ensuing years, she continued to write and record some of folk music's most enduring songs, including "Jesse," "Stars," and the Grammy Award-winning "At Seventeen."

Now, at 70, Ian is promoting her final solo studio album, The Light at the End of the Line, and its accompanying tour. The album offers a brilliantly crafted collection of songs on aging, identity, and gratitude, and is a bittersweet goodbye of sorts to those fans who have supported her for the last 56 years.

"There are people who literally have stood by me and bought my product when nobody else would, knowing that it was not going to be my best but supporting me nonetheless," Ian tells Next Avenue. "There have been people who have flown from all over the world to come to shows in anything from 80 seats to 8,000. So I think there's an element of gratitude for the gifts you were born with and gratitude for the people who recognize those gifts that comes with maturity."

"I normally try to insinuate my idea, like with 'At Seventeen,' so that before you're even dealing with the lyric, you're already accepting it."

She laughs, adding, "I couldn't possibly have been this gracious when I was younger and thought that I invented the wheel."

Next Avenue recently spoke with Ian over Zoom about the songs on the album, her complicated friendship with the legendary Nina Simone, and what she sees in store for her next chapter.

Next Avenue: What made you decide to release this album now?

Janis Ian: I decided after Folk is the New Black, which was 15 years ago, that if I made another album, it would be as impeccable as possible. It would be songs that lived up to the talent that I think I was born with, which means that I'm competing with my best work. I didn't want to put out an album the way that you have to put them out when you're with a major [label] where, ready or not, here you go. And I didn't want to put it out before I felt like the times made sense for it. You know, Dylan once said, when somebody asked him why he hadn't put out any product in a while, 'The times were not right for a Bob Dylan album.' I thought that was a really intelligent way to look at it. Because there are times that are better for my kind of music and times that are not. So it was a combination of that.

You wrote in your blog that 'Resist' is one of the best songs you've ever written, and it took you almost five years to finish. What was it about that song that was so challenging?

Speaking purely as a writer, sometimes you begin something and you realize you can't follow the regular rules that you've always worked with, so you have to break your own rules, which is really difficult. It was a different way of writing for me. I don't normally get that frontal. I normally try to insinuate my idea, like with 'At Seventeen,' so that before you're even dealing with the lyric, you're already accepting it. 'Resist' doesn't do that. 'Resist' just smacks you in the face right away. And it was one of the few songs that couldn't be finished until I could do it live. I couldn't figure out the ending. I couldn't figure out that it needed the spoken word section until I did it live three or four times and found where it was failing. Not in terms of the audience reaction, but in terms of my internal clock, if you will.

One of the tracks, 'Nina,' was written in homage to Nina Simone. Can you share a bit about your relationship with her and what impact she had on you, not only as a person, but as an artist?

When I was starting as a writer and a performer, Nina was the only woman who was doing everything I wanted to do. Nina was arranging, playing, singing, performing, leading the band, and writing. Even to this day, I'm not aware of someone else in my lifetime who was doing that in 1964 [who was] female. Carole King was writing with Gerry Goffin and Ellie Greenwich was writing with Jeff Barry, and they were singing their demos and doing the arranging, but they weren't out in the world doing that. Nina was it. So it was a huge influence. Her version of 'Pirate Jenny' is a masterclass in drama; how to leave things out, how to not over sing.

I think the first time I met Nina, I was maybe 15. 'Society's Child' had just come out. I got to know her better in my twenties and thirties, and [chuckles] she was not easy. It's rare that you run across someone who, in my profession, at least, is genuinely biologically disturbed. It's usually more badly behaved, or drugs or encouragement from the wrong people. With Nina, I wish that I had understood better what was going on. But we didn't know about stuff like that the way we do now. So my memories of Nina are in that song. It's not just the sense that lightning poured out of her as a performer, but also the craziness. I said to her once when she pulled a payphone out of the wall, 'Nina, you're not in reality. Come back to reality.' I don't know what she was seeing.

She was difficult, frustrating, lovable, amazing. To this day, I have not seen a better solo performer. She was astonishing. I tried very hard not to write that song. I had the guitar part, which turned into a piano, and it just kept coming back to her. I finally gave into it and wrote it.

You wrote 'Better Times Will Come' after the passing of John Prine, and that song led to The Better Times Project. Can you talk a bit about that project and how it came about?

The project began when I wrote the song a day after John died. It hit me very hard. I was doing laundry and the song just started to roll around in my head. And literally in between the washer and dryer and the folding, I wrote the song, sat down on our porch, sang it into my phone, notated it out, and put it up online.

John Gorka got hold of me and said, 'My tour's canceled. I'm worried about my rent.' And I said, 'Try singing this song and put up on Facebook. See what happens.' [It got] 70,000 hits and he sold a mess of merch [merchandise]. So I reached out to some other artists whose tours were being cancelled and said, 'You want to try and experiment?' The conditions were: they had to do it themselves from lockdown. They couldn't go somewhere fancy. They had to give permission for people to download it, to make videos of it, all not for profit. They had to give permission for me to put it on YouTube and Facebook. And in return, I would do whatever I could to help them.

It became people like Jane Hirshfield, the poet, whose book tour got cancelled, and then Sue Coccia, who could no longer do Liberty Puzzles, or [cartoonist] Dave Blazek. And then it became, what about my friends in other countries? Surely they need help, too. So then we had Dutch and Mandarin Chinese [versions]. And then it became, why don't we do sign language versions? Fans started suggesting people that they thought would be helpful. It turned into, I think, 180 different versions. I'm still sitting on 11 that I need to find time to get posted. I finally had to shut it down because there were so many people, and what was supposed to be a couple of weeks turned into months and a lot of money in web stuff.

It's part of what I always believed artists are supposed to do. We're supposed to give back and we're supposed to try and make things better when things are scary. And the amount of people that would come on Facebook or my website and say, 'I wake up every morning to the new version and it makes my day bearable.' To me that's doing what you're supposed to. What I'm supposed to do, anyway.

Though it was released in 1965, 'Society's Child' could still be relevant today. Even 'At Seventeen' doesn't feel far off the mark from what a lot of young people go through now. What is it like to know that a song you write could stand the test of time for decades?

I don't think about it when I'm writing. I think about trying to hit a universal to reach the maximum amount of people emotionally. Certainly with 'Society's Child,' none of us expected it to have the effect it did or the controversy. It's sad to me that both of those songs are still so relevant. It's a sad commentary on our country. I wish somebody like P!nk would cover ['Society's Child'] because I think it could lend some strength to a lot of people.

What did the experience of 'Society's Child' and the backlash it received teach you about the power of songwriting and music to affect change?

Exactly that: the power of a song. A song can pull together an entire movement. Look at 'We Shall Overcome.' A song can be a rallying cry. When I teach, I say, 'Don't forget, we sing them from the cradle to the grave.' That's what songs do; they live in your bedrooms and your living rooms, and your gravesides and your birthing parlors. It's important for us as artists to remember that because with that comes a certain responsibility.

"A song can be a rallying cry. When I teach, I say, 'Don't forget, we sing them from the cradle to the grave.'"

If you think no one's listening, it's really easy. One of the tricks as a writer, as Harlan Ellison said, is that you remind yourself that nobody has to hear it. Because it's too easy to fall into that trap of, 'It's going to go on an album. The record company will be listening. Radio might play it. People will be hearing it.' You can't write from that place for very long. It'll make you crazy. But it's important to remember how powerful a song can be because you're dealing with magic.

You launched your own record label a while back. What was the decision behind going independent completely?

I didn't want to have to answer to anyone. I didn't want to have to make albums on someone else's schedule. It took almost 25 years for me to find out that [the album] Aftertones came out before I thought it was anywhere near ready because the record company kept telling management and production that they needed it for their fourth quarter. I never want that to happen to me again. So once the technology became available, it was logical.

I think it's been good for me creatively, but I have five full-time jobs. I run a record company, a publishing company, my management, and my booking, and I'm still running a foundation. That's a lot of time. I haven't had a weekend off email, let alone a week, in probably 10 years.

I would like time to not be stressed, to not stress out my family with my stress. I would like to not know what I'm doing a year from now. I'm going to be 71 this year. I'd like a little less responsibility. I'm responsible for a lot of people. It's a lot, especially when it all stems from the only part of it that I'm actually really good at, which is being creative. None of this stuff exists without the writing. So why not go back to doing what I do best? And if it ends up being out there, great. If it's not out there, great, too.

You've written books. You've acted on television. You've had many years of success as a musician. And if all goes as planned, as of November, you will be done touring. What do you see as your next chapter?

Oh my God. It's just so many unfinished things. I'm not precluding the idea of going to Europe and the UK one last time. I think Japan and Australia are probably not going to happen, but I do miss those places. My wife and I were going to spend some time in Europe and the UK traveling around seeing friends, and that didn't happen. I'm not discounting the possibility of that. Otherwise, I have a book I want to finish. I have songs I want to finish. I would like to find out whether I will ever be a good short story writer. I'd like to narrate other people's work. I had a blast [narrating] 'Patience and Sarah' [a novel by Isabel Miller] with Jean Smart. I'd like to do more stuff like that.

And I would like to walk on the beach, as cliched as that sounds. I'd like to wake up in the morning and have no agenda. I find most artists create out of boredom, really. You know, you're bored, you start working. And I don't have time to be bored. I miss being bored. I like being bored.

Read More