Laid Off From White-Collar Work? Consider Manufacturing

How this sector is often welcoming to job hunters over 50

Although the coronavirus continues to rattle global markets and industries, some analysts expect to see greater demand for advanced manufacturing talent in the United States as the pandemic diminishes. That could create opportunities for older men and women, including white-collar professionals struggling to find jobs.

Before COVID-19, there were 500,000 manufacturing jobs open in the United States, according to the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). “We’re going to have a need very quickly to ramp up on hiring in those facilities that may have been shut down during the crisis or that need to expand operations,” said NAM president and CEO Jay Timmons in a recent press conference.

As manufacturers frantically try to keep up again with demand for essentials and lifesaving PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) for health care workers as cases rise across the country, their innovation and high-tech problem-solving could help dispel misconceptions that all manufacturing jobs are dirty and physically demanding, said Sara Tracey, project manager of workforce services for the Ohio Manufacturers’ Association in Akron, Ohio.

Manufacturing Jobs and What They Pay

Entry-level manufacturing jobs in industries such as aerospace, technology and defense include CNC operators, set-up technicians and programmers, as well as inspectors, higher-end assembly technicians and quality assurance.

“He said, ‘Why don't you think about changing careers?’”

The pay typically ranges between $35,000 and $65,000, including overtime and benefits, said Richard DuPont, director of community and campus relations for the Advanced Manufacturing Technology Center at Housatonic Community College in Bridgeport, Conn. More experienced professionals can earn upwards of $95,000.

In Ohio, manufacturers have been training and moving some workers into higher positions so the companies can hire and train new candidates for vacated ones, Tracey noted. Resources such as the Making Ohio website let people explore careers in manufacturing, including robotics, automation and 3-D printing.

Industrial maintenance is an important career pathway these days, as well, Tracey said. This sector is expecting more retirements in the near future, which will create jobs from “traditional machine mechanics to troubleshooting state-of-the-art electronic or robotic processes,” Tracey noted.

Connecticut, among other states, now offers training programs with community colleges, state manufacturers and other organizations.

From Banking to Precision Tools

This kind of training helped Allison Clemens-Roberts, who is 50+, find work after losing her clerical job in the pensions department of a Connecticut bank in 2017. A severance package gave her time to look for work, but she couldn’t find even temporary employment. She blames age discrimination by white-collar employers.

“There’s no way to hide how old you are. They can ask when you graduated from school,” Clemens-Roberts said.

But while she was out of work, Clemens-Roberts received a postcard from AARP offering a 25% tuition scholarship on advanced manufacturing programs at Goodwin University, a career-focused school in East Hartford, Conn.

She wasn’t interested until her husband Frank saw a TV commercial touting the benefits of Goodwin’s manufacturing and other programs.

“He said, ‘Why don't you think about changing careers?’” Clemens-Roberts recalled.

So, with several months left on her severance, she enrolled in a full-time, six-month CNC (Computer Numerical Control) Machining, Metrology and Manufacturing Technology certification program. It would prepare her for a job working with automated machine tools which requires mathematical skills, attention to detail and critical thinking.

Scholarships cut Clemens-Roberts’ tuition bill from $7,000 to $3,200. After a two-month paid internship at TOMZ, a manufacturer of precision components for major medical devices in Berlin, Conn., she was hired in April 2019. Six months later, TOMZ reimbursed Clemens-Roberts $1,500 for her education tab.

Clemens-Roberts said her family is now in a better financial position than when she was working in a bank, living paycheck-to-paycheck. Considered an essential worker, she has kept her full-time job through the pandemic, except for three days in March.

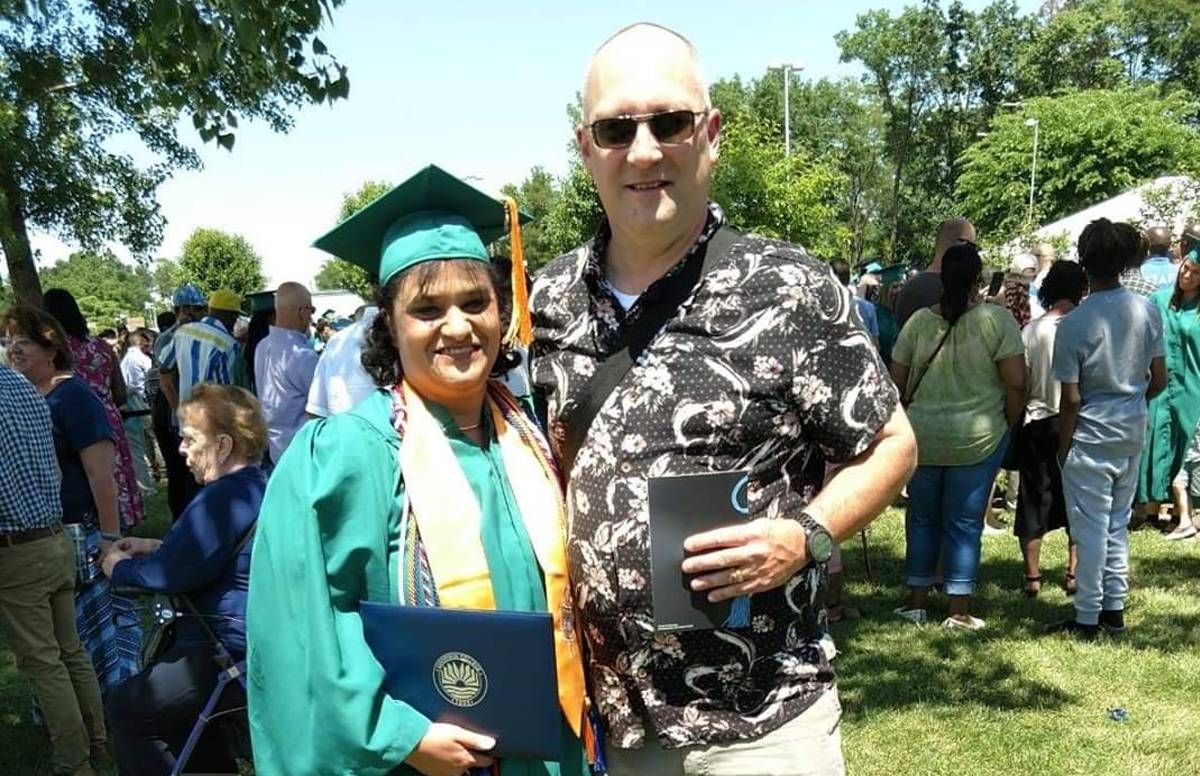

“I never thought I would go to college and participate in a graduation — in cap and gown,” Clemens-Roberts said. “That was a big surprise. And [actor] Danny Glover was the speaker. A bucket-list experience.”

There's “obviously age discrimination, among other things, at play” for job seekers over 50, said Nora Duncan, Connecticut state director of AARP. “The fact that one can get a certificate in about nine months and totally re-career into a nearly guaranteed job is an incredible opportunity for an older worker.”

While AARP helped Clemens-Roberts pay for the tuition initially, the internship helped her get hired as a machine operator.

Older and Younger Manufacturing Workers Helping Each Other

The search for skilled manufacturing labor across the country is creating opportunities for workers of all ages, said DuPont. And older and younger generations working together are assisting each other.

The older students help younger classmates with life skills, while younger students can help with technology,” said DuPont. “Together, they make excellent teams.”

Just ask Fernando Vega, 62, who is now a quality inspector at Forrest Machine, in Berlin, Conn. It makes precision-machined parts and other components for the aerospace and commercial industries. In the 1990s, he was a quality inspector before recessions and outsourcing forced him to consider other careers.

He tried working for a nonprofit and though Vega found the work rewarding, it wasn’t financially sustainable.

So, Vega went back to school in spring 2018 to study advanced manufacturing at Goodwin.

“I was in a class of eighteen, and at first everyone kept to themselves. But when it came time to read blueprints, there was some panic and I said, ‘Don’t panic, I’ll show you.’ The [younger] students helped me with trigonometry, and then we started to work together.”

Vega has worked at his manufacturing job throughout the pandemic. At one point, he was putting in 50 hours a week, but that was reduced to 40 hours plus overtime.

Vega recalled promising his mother that he would go to college. “But that was a long time ago,” he said. His mother never got to see him graduate but Vega feels he’s fulfilled his promise — not only to her, but also to himself. “I love my job,” he said.