Loss and Grief in an Increasingly Secular World

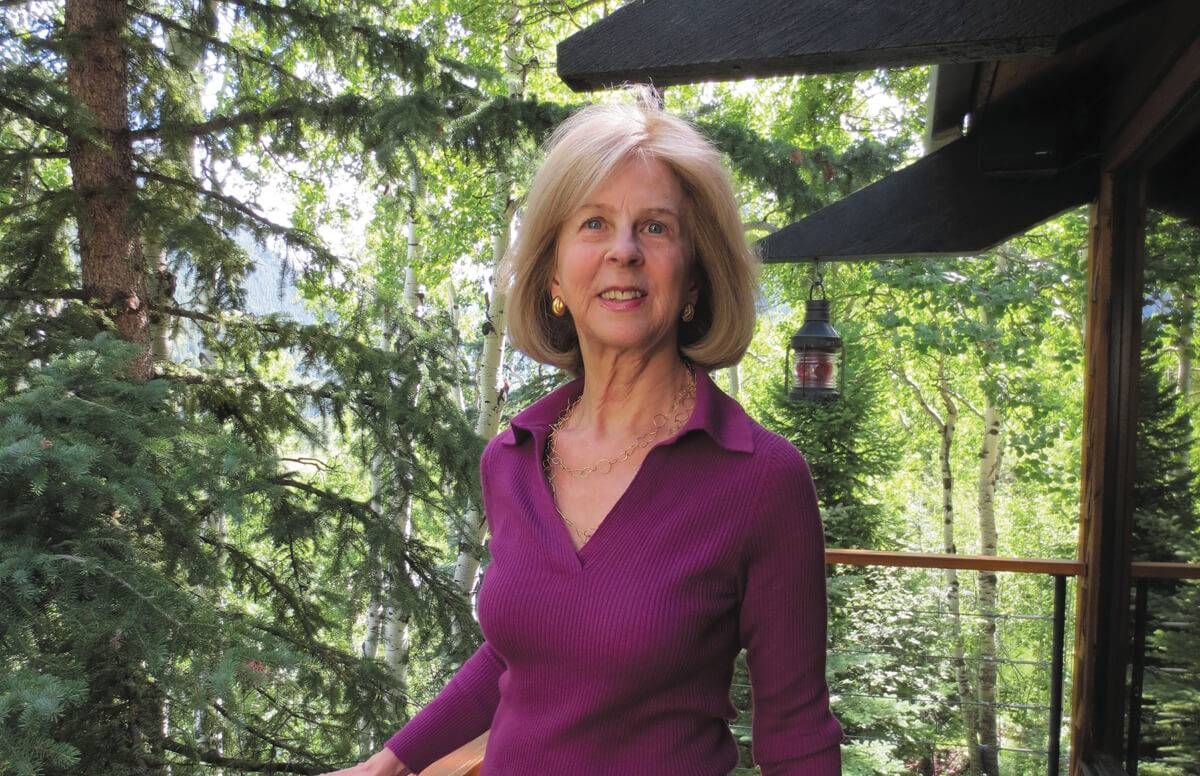

'Why Religion?' author Elaine Pagels talks about her struggles and finding connection

Elaine Pagels, 75, has lived through the best and the worst of times. She is the highly acclaimed author of a long list of scholarly, yet accessible, bestselling books, most notably The Gnostic Gospels; a renowned professor of religious history at Princeton University and winner of a host of prestigious honors, including the 1981 MacArthur Foundation “genius” award.

But these professional triumphs have been shadowed by the anguish of private grief. In 1987, her six-year old son Mark, who was born with a hole in one of the walls of his heart, died after a prolonged illness from a rare lung disease. The next year, her husband, physicist Heinz Pagels, fell to his death when the rocky Colorado mountain path he was descending gave way. He was 49. Pagels was left to cope as the single parent of two toddlers; her daughter Sarah and son David.

In her latest book, Why Religion?: A Personal Story, Pagels interweaves her intensely moving chronicle of grief with her journey as a scholar and seeker of the origins and history of religion. She spoke to Next Avenue about the nature of loss, the relationship between grief and religion and the role of the spiritual in our increasingly secular world. The telephone interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Next Avenue: More than 25 years have passed since the deaths of your son and your husband. Why have you waited until now to tell the story?

Elaine Pagels: I could not have imagined doing this before. Writing it took seven years, and it was hard because I had never written in the first person before and because I was writing about things I didn’t want to think about before. But after my children were grown, in their twenties and out of the house, these experiences emerged in a way that I did have to look back.

I realized that the work that I do as a historian is deeply connected with the questions and experiences I have had to deal with in my life. I wanted to weave those together. I didn’t want to write just a personal memoir, but [show] how the work was a way of exploring my own questions about why we bother with religion.

You write powerfully about the connection between grief and guilt, even when there is no reason to feel guilty.

Your greatest responsibility as a parent is to protect your child. When your child dies, it is as if you have failed, and the grief is huge. But the guilt can also be just as shattering. It was very important to me to come to an understanding that I couldn’t have done anything to prevent it.

And after your husband’s death?

Especially when there is an accident, people say: 'Why? Why me? Why him?' The survivors often feel guilty, as if you could have prevented it, and that is something I had to struggle with. The guilt masks an even more painful awareness that you are helpless, there was nothing you could do, you cannot change it, you have no input; and that is a worse feeling.

But it’s a truer feeling, and in a way more grounding, to realize there was nothing I could do.

How do you respond when people ask about your own beliefs?

After Mark died, when people asked, ‘What is your faith?,' belief in God seemed very abstract. What’s not remote is people gathering, people sitting and talking, the prayer, the music, the sense of shared experience and people participating and connecting with each other. These traditions, thousands of years old or older are ways and practices that move us to hope. And that is one of their deep values.

These days, I meditate and I go to an Episcopal church because the priest has a very deep spiritual sense, and the sense of place there is very powerful.

You write about your experiences with different religious groups through the years and how some helped and some did not. Which did not help?

When I was in high school, I participated in a close-knit [Evangelical Christian] group. After my friend Paul died in a car crash, they said he was going to hell because he was Jewish. I left the group and never went back.

And which did help?

When Mark was in the hospital, I felt grateful as I sank into a wooden pew at the back of a Lutheran church and listened to the choir sing the “Bach Reformation Cantata.”

In Colorado, I had gotten to know the Cistercian [often called Trappist] monks of St. Benedict’s Monastery and learned from them how meditation and contemplative prayer can bring calm. Although I am not Catholic, I often went to evening mass there. It was a deep well of silence, and that was helpful. And some of the Trappist monks said things that were helpful because they spoke to what was happening, rather than in clichés.

Is there of an example of a cliché that hurt?

When the policeman came to tell me that my husband was shockingly, and suddenly, dead, he said, 'God never gives us more than we can handle.' I thought: 'What makes you think I can handle this a year after our six-year old son died?'

He didn’t know that, or that we had just adopted two children. But I was livid. That kind of nice sentimental comment is just salt in a wound. I was standing by the deck of the house and I just twisted the handle of the door and it came off its hinges. I couldn’t speak, I was speechless.

And yet you did go on.

There’s the line from Samuel Beckett, 'I can’t go on, I’ll go on.' Yes, of course we go on, and that’s amazing. It’s amazing how resilient we are, far more than we ever could imagine.

How do we do that? With me, it had to do with friends, with time and with exploring the emotional intensity of what had happened. And the work that I do also became a means of struggling through some of these experiences.

The stories in the Hebrew Bible, in Genesis and Job, for instance, and the death of Jesus — these are such powerful stories. We still read them because they speak to the complexity of the ways we experience loss.

By contrast, the awareness of the complexity of dealing with loss is so often simplified and stripped of the huge emotional spectrum and the enormous range of ways that we find to go on.

These days, many people prefer to say they’re 'spiritual,' rather than 'religious.' How do you interpret that?

There are enormously powerful ways religions shape our identity and our feelings even when we’re unaware of it and not religious.

I think that people who say 'I’m spiritual' have usually been either harmed or turned off by institutions. They feel alienated from them. They are aware of a need to have a spiritual dimension in their lives, but can’t do it through an institution.

Are there alternative ways to find that kind of powerful connection?

Not everybody needs religion. My husband’s sense of transcendence came through physics. I also know many people who find that articulated through poetry, music, art or helping people, whether as part of a community, a volunteer or being a doctor or nurse.

For me, the power of story and emotion connect me to religion. I need to engage these traditions. I feel the need for connection with other people. But it’s not necessarily a matter of belief.