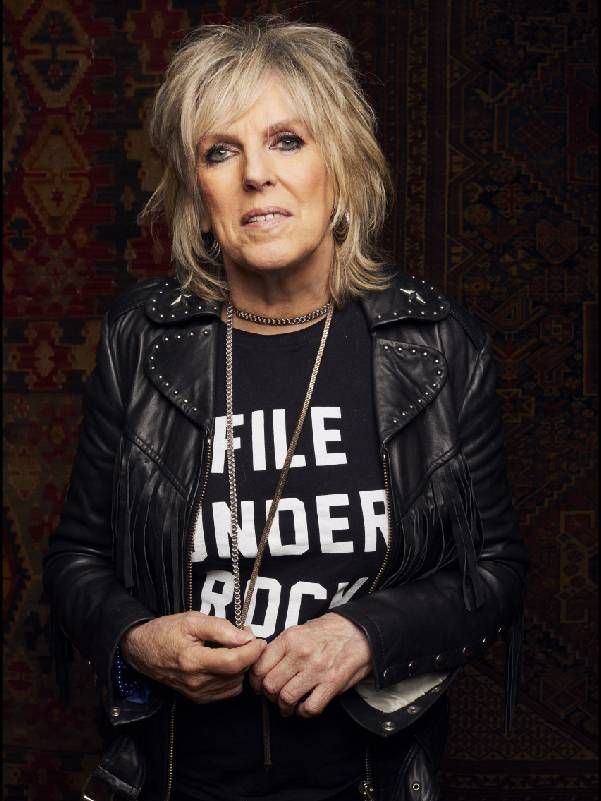

Lucinda Williams Is Telling Secrets

At 70, the singer-songwriter, who has recovered from a 2020 stroke, finds new ways to live creatively and has a memoir and an album to show for it

Singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams is known for the spare honesty of her musical stories filled with quirky characters and telling details.

Now in a case of art inspiring art, Williams has released a memoir called "Don't Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You" that combines tales from her personal life and career with anecdotes about the direct inspirations for her songs.

In a writing voice that's as plaintive as her vocal style, the three-time Grammy winner recounts an itinerant childhood as her poet father Miller Williams moved the family multiple times before becoming a professor at the University of Arkansas in 1970. Her parents divorced in the mid-'60s and her father retained custody of Williams and her two siblings. Her mother, Lucille Day, struggled with mental illness for much of her adult life and, according to the book, was sexually abused as a child.

In 2020, her home in Nashville suffered damage from a tornado and later that year Williams had a stroke that left her with impaired motor skills on her left side.

In "Secrets," Williams details the life of an up-and-coming performer — including the day jobs, dive bars and bad relationships that would fuel her writing — and the stop-start journey that would culminate decades later in a sold-out performance at Radio City Music Hall.

Now 70, Williams has overcome some major challenges over the past few years. In 2020, her home in Nashville suffered damage from a tornado and later that year, Williams had a stroke that left her with impaired motor skills on her left side. She learned to walk again but was unable to resume playing the guitar.

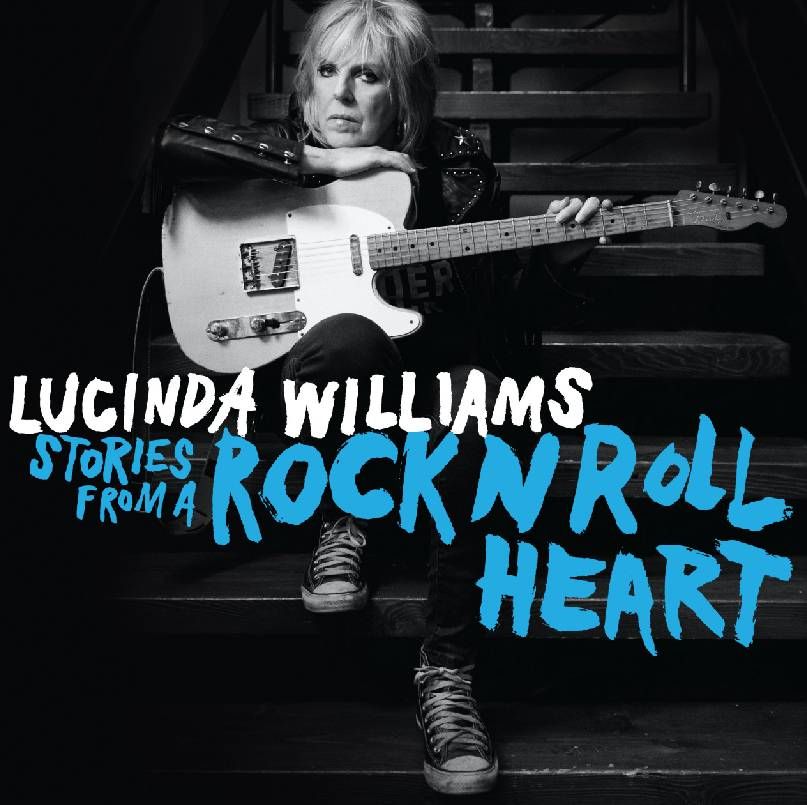

Her new album, "Stories from a Rock n Roll Heart," which comes out on June 30, is her first release since the stroke. Produced by Williams, her husband Tom Overby and Ray Kennedy, it reflects a greater level of collaboration than ever before and features special guests including Jesse Malin, Margo Price, Jeremy Ivey, Angel Olsen and Buddy Miller.

Williams talked to Next Avenue about staying true to her musical instincts, finding success at mid-life and having to pivot creatively after her stroke.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

As a musical storyteller, how did writing your book compare to making a record?

I don't record a song until it's finished and it's ready, and I decide when it's finished. That's the difference — I have more control.

How do you know when a song is finished?

It's kind of gut instinct. I collaborate a little with my husband Tom — he's a good sounding board. It's important to have someone like that you can bounce stuff off of — he's honest with me and will tell me if it's not that great or doesn't seem finished.

Then when he says he really likes it, I know it's really good.

I also used to show things to my dad. A lot of times when I was just starting out writing songs, I would show him lyrics, and sometimes he would point something out and make a suggestion — little bitty things that would make a difference. It was kind of like an apprenticeship.

"I felt a bit embarrassed, writing about all these boyfriends. I had this crush on this one and this crush on this one."

One time I was working on a song, a descriptive thing that said 'blue dress.' My dad read the lyrics. He knew what I was writing about, and he said, 'Honey, it would be much more descriptive if you said something like sad blue dress,' which of course was wonderful.

Remembering Crushes

In your new book, you recount the real people and situations that helped inspire your material. "Lake Charles," for example is about a colorful ex-boyfriend from the '80s who said he was from Louisiana but was really from East Texas, while "Greenville" came about from a random encounter with a Vietnam War veteran from Greenville, Mississippi. What was that like to go behind the music, especially when talking about ex-boyfriends and crushes?

I felt kind of shy about certain things and also worried what the person is going to feel like — the person I'm writing about. Am I being sensitive enough and how is it coming across? I didn't want to do that too much because I didn't want to censor myself. That's something my dad taught me. I had to balance that.

I felt a bit embarrassed, writing about all these boyfriends. I had this crush on this one and this crush on this one. I was worried people are going to think I'm a nut. I thought it sounded adolescent.

But they were crushes; I didn't know how else to say it. It's like a 70-year-old woman shouldn't say that. Maybe I'm going to bring the word back.

You write that the book took a lifetime to come together. What were some of the challenges you faced as a writer?

On the one hand, I felt ready. But as I got going with it, I didn't know how to get started. When I write songs, I have the luxury of waiting until I'm in the mood — I couldn't do that with this book. I had to sit down and write down all this stuff that I wasn't necessarily in the mood to write about or think about.

Creative Inspiration

I'm not used to writing against a deadline. What would happen is I would write a bunch of stuff and a few weeks later, I realized I'd forgotten something, or I would read something and wouldn't like what I'd written. I'm a natural-born editor — I can't read without editing. That became a big challenge — I always wanted to change things or fix things.

You grew up among a world of creative people. What did you draw from your childhood, as far as music is concerned?

There was a little bit of a generation gap with my dad as far as music. I loved the Doors — he wasn't into them. But there was a lot of stuff we both listened to — blues stuff and R&B — and my mother loved folk music. She turned me on to Joan Baez and Leonard Cohen. That led me into the whole contemporary folk scene — Bob Dylan, Gordon Lightfoot, Buffy Saint Marie, Judy Collins.

I would try to learn some of those songs; those were the easiest songs to learn and sing. I used to feel self-conscious because I wanted to learn to sing like Joan Baez and Judy Collins with these beautiful high voices. But it wasn't my natural range.

Then I got introduced to Bobbie Gentry — she changed those things. Her voice and songwriting made a huge impact on me. She had this smoky lower range, and the way she looked and everything — the whole package. Then I had someone to identify with in that way.

As you write in your book, you wanted to rock like Chrissie Hynde (of The Pretenders) but were considered too country, while the country establishment thought you were too rock for Nashville. How did you break through those limitations?

The Key is Perseverance

Just perseverance — that's pretty much what it was. I still had this urge to go out and sing. I enjoyed the feeling of getting up on stage and doing that.

Moving to LA in the '80s marked a turning point. But it wasn't easy because you were playing shows at clubs like Raji's in Hollywood, where the pay was $5 for the band.

I was living in LA, and there was that feeling where you think you need to be in a place like this. When you go out, you never know who you might run into, even if you're playing a dive like Raji's. The head of Sony Records might come in. Those little feelings of hope would find a place to live in my mind.

It was exciting — that sense of who knows what might happen. As long as that's there, that's what propelled me forward. I got enough encouragement from other people. The LA Weekly was really supportive, and I had other musicians who wanted to play with me. All of these things combined helped push things forward.

At age 45, you achieved mainstream success with the Grammy-winning "Car Wheels on a Gravel Road," which took six years to produce. Did you always have the belief that something big would happen with your music?

"I used to feel self-conscious because I wanted to learn to sing like Joan Baez and Judy Collins with these beautiful high voices. But it wasn't my natural range."

Maybe it's because my dad was hell-bound for some kind of success on his road as a writer — he ran into some big boulders along the way, and also he was a Southerner. Back then, it wasn't considered cool to be from the South, and then it got cool. When he was first starting out, he ran into some issues with that around New York publishing companies, the New York literati world — they didn't get it, they didn't get him.

I think I picked up his attitude about them, which was f--- them. But you have to know when and where to say that. I had good instincts about that sort of thing, being at the right place at the right time. I remember knowing other artists who would get offered a pretty good publishing deal but would turn it down because the percentage wasn't high enough or something. I would say: 'But it's a good step, just take the step, and then you move into something that's better later.'

You describe being starstruck when you met Bob Dylan in 1979 at a club in New York City. What did that teach you about fame?

It's good to have those moments, it's good to be starstruck, it's good to have somebody to look up to who you feel is a little bit better than you are — or more than a little bit better. I wish I could do what he or she does. Aspirations are good — it's part of that fairy tale world — that's where I want to be.

But then [years later] I went out and opened for Van Morrison and Bob Dylan. They were playing in big arenas. I thought they were going to be hanging out after the show and we would be sitting around and telling stories. They kept to themselves, and no one seemed really happy.

I saw that and said, 'I don't really want this.' This isn't the part I want to aspire to.

Special Guests: Springsteen and Scialfa

You had a much more positive experience when you met Bruce Springsteen after one of his performances and got to have dinner with him. Fast forward to your new album, and Springsteen and his wife, Patti Scialfa, are singing backing vocals on the first single, "New York Comeback," and the title track.

The Boss — it still blows my mind that he's on there.

How did you get them to sing on the record?

We got a couple of songs written and hadn't gotten them cut yet. We were sitting around the table, talking about different songs and fantasizing about who we would like to get.

Jesse Malin was involved in a lot of the co-writing, and he said, 'I know some people who can reach out to Bruce.' He's from New York, and he's like the mayor of the East Village, and he just knows everybody. He managed to get an invitation out to Bruce and Bruce said yes — he and Patti, both. We sent them the tracks, and they did their thing. We didn't tell them what to do. Then we got [the tracks] back, and we were doing the happy dance.

What was it like for you to write songs without being able to play guitar? Me not playing guitar is what led up to the cowriting thing. I thought I've got stuff in my head. If I could find somebody to be me on guitar, that was what led to the collaboration thing. Another friend of ours — Travis Stephens (our tour manager) — was part of that effort, too. He jumped in and offered quite a bit of musical and lyrical support. That was the first time I ever collaborated like that.

"We sent them the tracks, and they did their thing. We didn't tell them what to do. Then we got [the tracks] back, and we were doing the happy dance."

I was never interested in it before. After I moved to Nashville, everybody was cowriting, and I wasn't into it. Then I realized if you know the people, so much of it has to do with who it is. In this case, it was Tom and Jesse and our friend Travis. It felt more organic. It wasn't like a forced set up time, like a meeting: I'm going to write with so and so at this time on a Wednesday. I enjoyed the collaborative effort in this case, and we got some good songs.

How was it to work with your husband in a creative context?

As it turns out, Tom, much to my surprise and delight, is a really good lyricist. I didn't realize he had been interested in creative writing for a long time. At first, he was kind of shy and I was kind of shy about it. Neither one of us was sure about working together in that capacity. He said, 'I've got these lines, you don't have to use them, but I thought I would show you just in case.'

At first, I was thinking, 'Oh no, what if I don't like them?' Then I would look at them and they were good. A lot of the songs came from his ideas, it was very satisfying to see the songs come together like that.

You seem at peace with your past. Did the book help you process it or was it something you had to reach to write the book?

I think I had to come to terms with it before — [writing a book] brings up a lot of stuff that you feel like isn't resolved.

A funny little thing: I was sitting backstage after a show with Roseanne Cash, and we were talking about this very thing. She leans over and smiles, and says, 'Lucinda, you don't have to be James Joyce.'

I said: 'That's the problem. I want to be James Joyce.'