Making Peace With the Road Not Taken

The 'How Did I Get Here?' author on looking back at 50

If you’ve hit the half-century mark, odds are you’ve asked yourself: Would my life have been better if I…? You can fill in the rest of the sentence, but it likely concerns a career decision you made early in your adulthood.

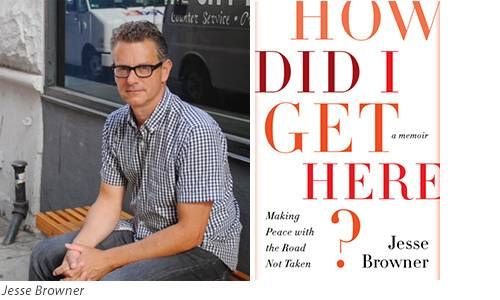

In his thought-provoking new memoir, How Did I Get Here?: Making Peace With the Road Not Taken, New York-based novelist Jesse Browner, 54, reflects on a key choice he made around age 30: taking a full-time, secure civil service job and writing for pleasure on the side. He runs a small language service for the United Nations, a kind of Congressional Record for the UN, and has squeezed in early-morning time to write five books before this one.

I just interviewed Browner about his riff on the classic Robert Frost poem (you remember, the traveler encountering two paths and taking “the one less traveled by” which “has made all the difference”). Browner, who is married to an editor and father of two, revealed what he discovered about himself and offered a way for the rest of us to not look back in anger — or regret.

Incidentally, if you’d like to read an actual line-by-line assessment of The Road Not Taken that will likely change the way you think about the poem, pick up the new book by New York Times poetry columnist David Orr, The Road Not Taken: Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong.

Highlights from my conversation with Jesse Browner:

Next Avenue: Why did you decide to write this book?

Browner: I’d known from a very young age that the only thing I wanted to do and that I was good at was writing. Yet somehow, I strayed from that path and took this job at age 30 — the first job I’d ever had and I’ve been in the same job ever since. I’m the very embodiment of the man in gray flannel suit.

I wanted to ask myself: Have I damaged myself as an artist and my career as a novelist because of the decisions I made?

What was your answer?

The exercise of writing the book taught me that I am doing exactly what I want to do. I focused on the idea that if only I had not taken this job, my life would’ve been completely different. And I found the more I focused on it, the more unreal and untenable that was. Taking the job was not in any way a cause of anything.

Any feeling that I’d made an error over the past 25 years was a result of an imperfect understanding of my own impulses and seeing myself through the lens of a 25-year-old man.

You write that you started thinking about ‘the road not taken’ when you turned 50 and felt trapped. Why did you feel trapped?

As I’m sure anybody who reaches the age of 50 knows, at that age, you tend to enter your most productive years and if you’re smart, they’re years when you take on a lot of commitments, especially financial. We had two mortgages, our kids were in private school and they were likely to go to private universities.

As a literary novelist, I had very few options; I had to make money. And once you assume commitments, you have to see them through.

So were you feeling sorry for yourself?

Not at all. I feel grateful for what I have. But I’m still curious about the lack of self-understanding that brought me to this path.

Do you think many others in their 50s and 60s are asking the same question you did?

Judging from the reaction to the book, and from people I talked to while writing it, a lot of us are; there’s no question about it.

Virtually nobody I know achieved exactly what they set out for at 25. It makes us feel inadequate or subject to failure at some level. Nobody wants to feel like a failure.

What can the rest of us learn from your introspection once we turn 50?

The conclusion I came to in writing the book is that when we reach this age, in many cases we have to learn to unsee ourselves, erase the image we have built up like grime on window over the past 25 or 30 years and that has become clouded and inaccurate.

When we reach 50, we’re in exactly the right position to take a big cloth to that window and clean it off so we can start again.

People our age tend to think of 40 as the age of maturity, because that’s what it was for our parents. But now, so many of us will remain productive so long, when you reach 50, it’s probably safe to say you’re in the middle of your adult life, with 30 years of adulthood behind you and probably 30 years ahead.

It’s the perfect moment to pause in your ascent and take a breath and really try to reinterpret your own sense of who you are.

Time is more limited, and you don’t want to resume that ascent with unnecessary, obsolete clutter. You want to get rid of as much baggage as you can since you’re about to climb the most important part of your journey.

Is there really one moment or one decision that separates a person’s life in two: before and after? You write that a “before and after scenario can be very seductive.”

I come to the conclusion that, for the most part, that’s a fiction. If we have a sense of before and after, we use it as a crutch. But that’s not true for people who’ve experienced tragedy in their lives — if they lost a child or had a near-death experience.

In my case, I had to shed this idea there was a before and after period in my life. The idea that my first wrong turn was when I decided to take a full-time job was a complete fiction. My life was already changing in many ways. Taking a job was not at all a watershed moment; on the contrary, it was one manifestation of changes that were inexorable and fully developed.

How would you tell people who want to make peace with the road not taken?

I’d tell them, just like the Robert Frost poem, the whole idea of the road not taken is essentially irrelevant. You have to remind yourself that you are a free agent and most of the decisions you made in course of your life you made freely.

I don’t know if this works for everybody; I know it works for me: Instead of focusing on what I didn’t do, I started focusing on what I did do and gave myself enough credit, for once, that the decisions I made were oriented toward what I really wanted. I realized my entire life was a vector pointing at things I wanted even when I was unaware of wanting them.

What’s your interpretation of The Road Not Taken poem?

Most people read the poem and interpret it as a roadmap for the American way of life: If you take the road less traveled, become the rugged individual and don’t let societal expectations guide your decisions, that will make all the difference in your life, so you can realize your full potential.

There is virtually no evidence in the poem or in Frost’s life to justify that interpretation. Also, he says taking the road made all the difference, but he doesn’t say if it is a positive difference or if he is talking from jail or the bottom of a ditch. Maybe he has had a terrible life.

He’s saying that no matter what you do, you’re always going to be thinking about what you didn’t do, that whatever road you chose could make a difference. But the difference is all in your head.

Character is destiny. Who we are is infinitely more important than what we’ve done.