Malaria, My Mother and Me

What happened when I was a baby and how that changed my mom's life

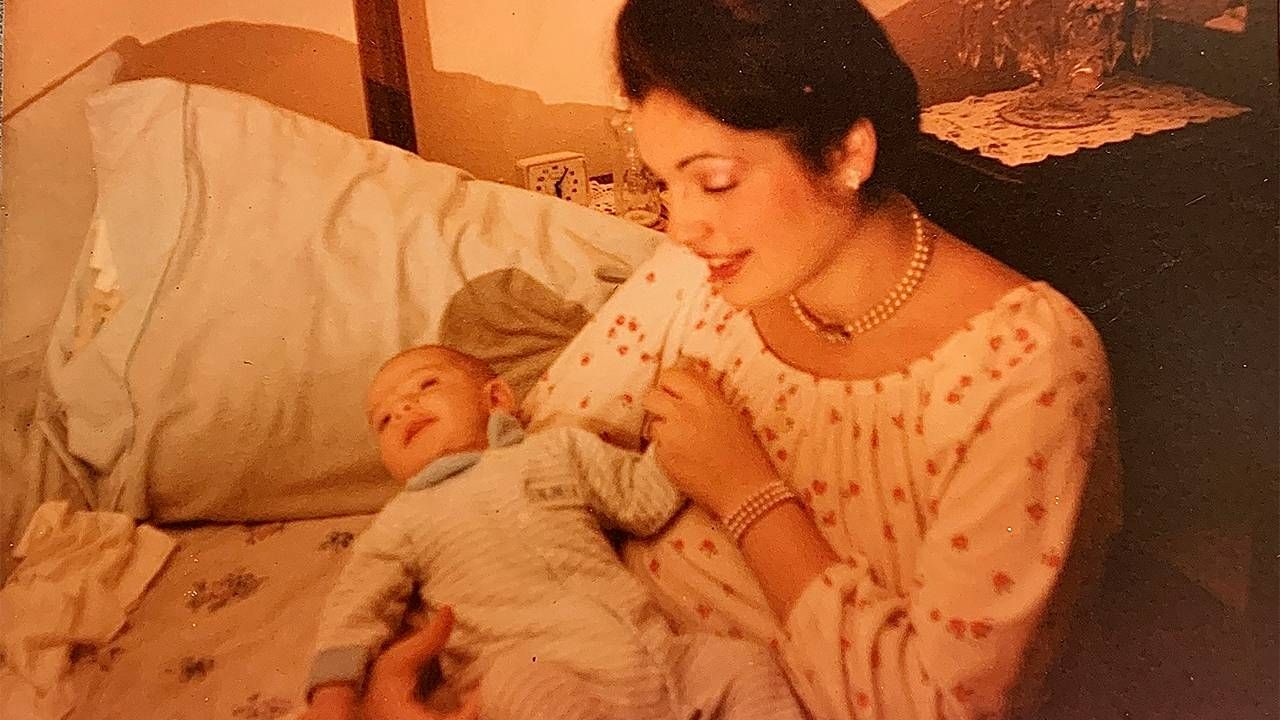

I was less than one-year-old when I contracted malaria in 1988. At the time, my mother Loretta, an Italian and Puerto Rican American from The Bronx, and my father Roop, an Indian American who'd emigrated to the U.S. a decade earlier, brought my four-year-old brother Ravi and me back to my dad's homeland for the first time to meet his family.

Before departing from New York to Mumbai, Ravi was given travel vaccines. I was deemed too young to receive shots and given only spoonfuls of a basic prophylactic as a preventative measure. Each time my mother tried to give me the bitter syrup, I spit it out.

Barely 30, my mom was nervous to bring her young children across the world to a country mostly unfamiliar to her. Only a few months earlier, she lost her father to cancer at 50. So, between giving birth to me and accompanying my grandfather at his bedside as he lay dying, she'd spent most of 1987 in hospitals.

Still, although apprehensive, this trip was an opportunity for her to set aside an arduous year.

A Trip to India, Then a High, Consistent Fever

India was still a developing nation in 1988, lacking proper health care and hygiene for many of its citizens. Although we were safe at my father's parents' home, my only protection from deadly insects was a light cloth over my face during the day and netting around my crib at night.

My mother practically lived in the Pediatric Ward, sleeping in a chair by my bed each night.

My mother did her best to protect me, but Mumbai's crowded, dirty streets and natural elements were difficult to avoid.

Upon returning to New York, she was relieved to have her children back home after a long and exhausting trip. But within a few weeks, I developed a dangerously high fever of 104°F. My mother rushed me to the ER where I was given a chest x-ray and treated for flu-like symptoms. The doctors waited for my temperature to drop and sent me home that day.

A few days later, the heightened fever mysteriously returned, I was rushed back to the hospital and received a second chest x-ray. The doctor merely advised my mother to give me an ice bath. It didn't work.

Days later, the fever returned. Another ER visit and chest x-ray. Nothing could be done, the doctors said.

Finally, after the fever reappeared for the sixth time in three weeks, now 106°F, the doctors finally admitted me for further evaluation.

I remained in the hospital for three more weeks as doctors poked and prodded me with needles and instruments, continuously drawing blood to determine the problem. My mother practically lived in the Pediatric Ward, sleeping in a chair by my bed each night.

In and Out and In the Hospital

By week three, a specialist in tropical diseases was called in to check me for malaria. However, after more tests, there was no sign of the disease in my blood.

"Two or three times a day, I brought you into the examination room, so they could draw blood," my mother recalled. "It was terrible. You cried and screamed and I had to hold your little black-and-blue arm down so they could inject the needle."

My mother was in agony, certain it was malaria. But no doctor in the hospital was confident enough to make that conclusion. We went home again.

A few weeks later, the rapid fever returned and the process started all over.

That year, my family spent most of their free time at the hospital. My mother became so familiar with the floor staff that she knew them on a first-name basis. She took out library books to study my symptoms, trying to convince the doctors that I had malaria. They disagreed, while remaining puzzled by my condition.

However, during one examination, a doctor pulled my mother aside to confide that he believed I had contracted a deadly form of malaria. Because that wasn't detectable in my bloodwork, though, he couldn't present a case to treat me for it. He advised my mother to prepare for her son's imminent death.

My parents then got ahold of my dad's cousin in Nevada who, as a student in India, studied malaria closely and treated patients in small, remote villages. After explaining my year of symptoms, he agreed that I was a victim of the disease.

He called my pediatrician and presented his argument over the phone. Whether the hospital doctors respected his opinion or not, or were simply desperate for another professional opinion, they finally prescribed the immunosuppressive malaria drug Chloroquine.

Within a couple of days, my symptoms faded and I was discharged — for the last time. Though we were warned my symptoms could return for up to nine years, they never did.

What My Mother Wound Up Doing

Inspired by the experience and by the nurses who cared for her baby, my mother soon enrolled in a local community college to study nursing. Her career as an RN lasted nearly three decades.

A few years following my traumatic episode, my mother and I went to the pediatrician for a routine checkup. Our regular doctor was out, so her substitute stepped in to give me a physical.

My case had been presented as an effective solution to treating malaria in children.

"This is your son?" he asked my mother, seemingly excited to meet me as if he'd known me.

He went on to explain that I was a featured subject at a national conference for doctors a couple of years prior; my case had been presented as an effective solution to treating malaria in children.

My mother was stunned, yet also proud that our experience had been used to help others. Today, I wonder if my case really provided any aid toward the understanding of the treatment of malaria. I like to think it may have helped doctors take visible signs and symptoms of malaria more seriously when test results fail to produce sustainable evidence.

Three decades after my malaria scare, the pandemic has only served as a reminder of humankind's vulnerability toward diseases, no matter their origin.

What My Story Can Teach Us All

Until recently, however, most foreign-born diseases were deemed a minimal threat to Americans. From our historical vantage point, it appeared that deadly viruses were pretty much a problem for people of developing nations.

It's true that diseases are among the top causes of deaths in low-income countries due to communicability, poor living conditions and nutritional deficiencies. It's also evident that a 140-year-old disease like malaria doesn't reach the United States frequently. About 2,000 cases are reported here annually, compared to more than 200 million cases worldwide as recently as 2018, resulting in over 400,000 deaths.

Only time will tell if new advancements in medical technology will rid the world of malaria and other deadly diseases. But for now, we shouldn't let our guard down.