Measles Outbreak: Do You Need a Shot?

A Q&A about measles with two infectious disease experts

(This article appeared previously on the PBS NewsHour website and it is an abridged version. Click here to see the entire article.)

The U.S. could be eight months or so away from losing its “measles-free” status.

The measles virus was eliminated from the U.S. in 2000, meaning there was no longer continuous transmission of the disease for more than 12 months anywhere in the country. Since then, the disease has occasionally sprouted up due to travelers, mostly Americans, getting infected abroad and returning home. Though those outbreaks create public health hazards, especially for children and pregnant women, the incidents tend to stick to single locations — Anaheim, California, in the winter of 2015 or Minnesota in 2017 — and then fizzle out.

That trend started to shift last October, when New York City — namely Brooklyn and Queens — began reporting continuous measles episodes. On Monday, as the epidemic in Washington State came to a conclusion, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced new outbreaks in Los Angeles, Sacramento, Georgia and Maryland.

Outbreaks in Nine U.S. Counties

Outbreaks are now ongoing in nine counties in the country, and 2019’s case count of 704 is the nation’s highest since 1994’s tally of 963 cases. (Reminder: It’s only April.) On Friday, two Los Angeles universities quarantined more than 1,000 students and staff members, meaning they were confined to quarters on campus or sent home— and President Donald Trump, who formerly spread misinformation about vaccination and its false connection to autism, encouraged unvaccinated children to get immunized.

If the U.S. loses its “measles elimination” status, it will join Venezuela as the only other country in North and South America with this distinction. Measles was declared eliminated across the Americas in 2016, but within a year, an outbreak sparked in Venezuela that has persisted up to the current day.

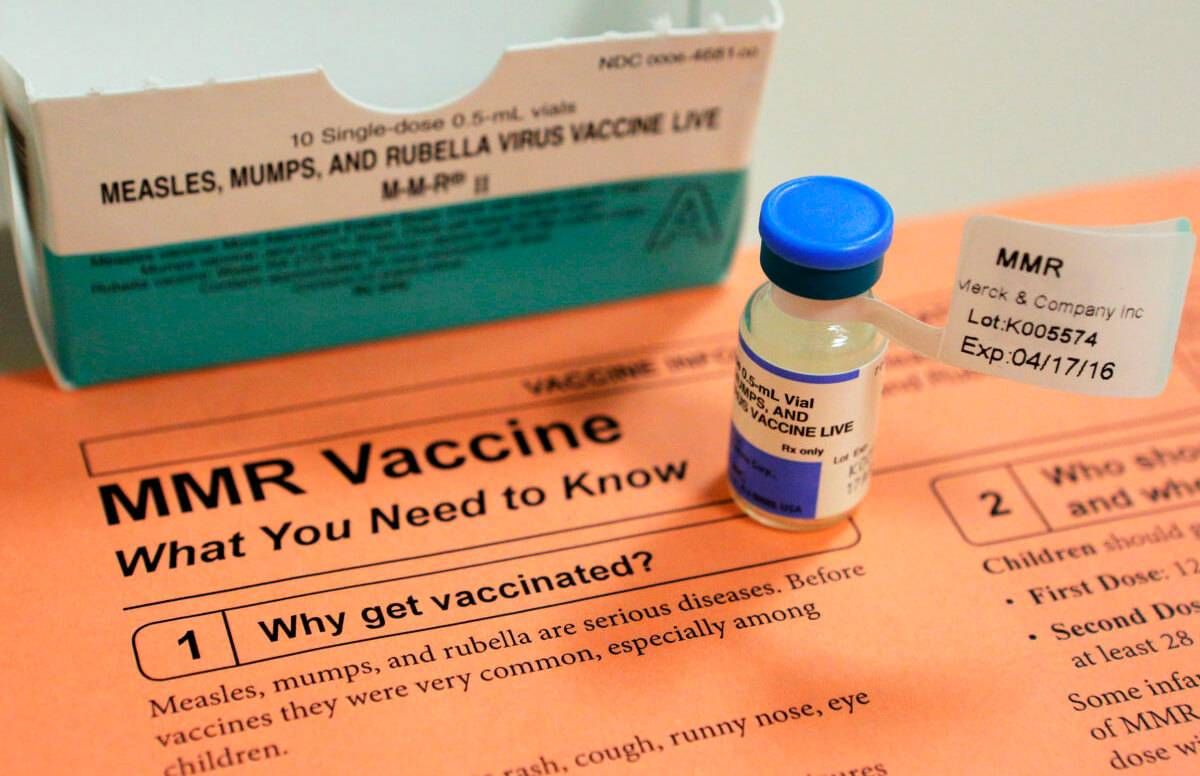

For most Americans, these outbreaks are a bittersweet wake-up call about the importance of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. Thanks to the success of vaccination programs, most people are unfamiliar with measles itself — which means they may be unsure about how to approach these outbreaks and protect themselves.

The PBS NewsHour posed these questions and concerns to two experts: Stephen Morse, director of the infectious disease epidemiology program at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and Dr. William Moss, a infectious disease epidemiologist and pediatrician at Johns Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Who is most vulnerable during a measles outbreak?

Stephen Morse: Children are usually the major targets in part because the youngest children don’t have immunity at all.

Dr. William Moss: Because the vaccine has been so effective in the United States and around the world, I think people have forgotten about measles and have underestimated the risk of measles. [Globally,] more than 100,000 children die each year, or about 300 children per day. Measles can also cause lifelong disability [such as deafness].

Morse: The virus can incubate slowly in the brain over years. Then suddenly, usually when the patient is much older [up to 10 years after a person has measles], the infection will reactivate and you get this very severe progressive inflammation in the brain called Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE).

[SSPE has long been considered rare, but a 2017 study from the California Department of Health estimated 1 in 600 infants developed the condition after they caught measles.]

What if you’re a healthy but unvaccinated adult -- should you be worried about catching the measles?

Morse: There are actually serious complications that occur in unvaccinated adults who catch measles, namely pneumonia.

Pregnant women are certainly at risk too. These issues may not be as well publicized as the Zika virus, but measles-related pregnancy complications exist [such as stillbirths, miscarriages and low-birth weight]. There were a lot of those going around in the old days.

That said, pregnant women should avoid getting the MMR vaccination for the same reason that measles infection is so dangerous for them: Their immune systems are compromised. Once their child is born, they can get vaccinated and do things like breastfeed without any concerns. Should anyone else avoid taking the vaccine?

Morse: People who have immunosuppression or some immunodeficiency, which are considered rare exceptions.

If you think you have the measles, what’s the best course of action?

Morse: Stay home and call your doctor or your health care provider before you head to a medical office or emergency room. If you do visit a doctor’s office or ER, immediately notify the staff, so they can take the proper precautions.

What if you’re an older adult and you had measles as a child? Do you still need to get a shot?

Moss: This is somewhat arbitrary, but we generally say that people born before 1957 are immune, because almost everyone got measles before then. The vaccine was introduced in the United States in 1963.

Morse: And we believe that if you actually had it and recovered, you have lifelong immunity, which is good.

Moss: So, there’s no good evidence that once a person has developed protective immunity to measles, either because they had the infection before or from the vaccine, that that protection wanes over time.

But America has experienced recent bumps in another disease -- the mumps, which I heard was due to the immunization wearing off?

Moss: That’s a great question, and you’re exactly right. What we’ve learned in the past couple of years because of large mumps outbreaks, particularly on college campuses, is that it does appear that immunity to mumps virus wanes. It’s recommended during mumps outbreaks that individuals who’ve had prior mumps vaccine get an additional dose if they’re at high risk for exposure.

There’s no evidence that the immunity to rubella wanes.

And if waning immunity was a real phenomenon with measles vaccine, we would be seeing these outbreaks spreading out into the general population and particularly affecting older adults, and we’re just not seeing that.

Right. So to recap: If an adult catches the measles, it most likely means that they never had the disease as a child or they only received one dose of the vaccine in their life. That means if you were born between the late 1950s and 1989, then you might want to get another MMR shot?

Morse: Yes. What we say to people is if you’re not sure about your vaccine status, especially if you’re traveling, take another MMR shot.

What do you do if you can’t remember if you were vaccinated or lost your documentation?

Moss: There is a blood test to check for measles immunity. It can measure if your body is making antibodies to the measles virus. Those antibodies have a pretty good correlation with protection. It is what we call a serological test.

It’s used, for example, to test health care workers. We want to ensure that the employees within hospitals — nurses, doctors, other employees — are immune from measles, to not only protect that individual but to prevent the spread of measles within a hospital.

At the moment, it’s not widely used during outbreaks or in the general population. But it is being increasingly used to identify susceptible clusters of individuals outside of the United States.