Meet the Auntie Sewing Squad

A group of Asian American women from across the country started by making masks, which inspired a book about how sewing is connected to racial and ethnic issues

Performance artist and comedian Kristina Wong planned to go on tour in March 2020. For reasons we're all too familiar with, she didn't, leading to her feeling depressed and unsettled, both by the loss of her occupation and the global pandemic.

Wong sews pieces for her shows, so at the beginning of the pandemic, when trying to think of a way to help, she hit upon making masks. Wong felt getting these to people in great need — farm workers, members of Indigenous communities, and people in prison — was the most patriotic thing she could do.

"I'm never going to be in the position where people are like, 'Oh, if I don't have some smart social commentary, I'm going to die,'" Wong said. "That never happens. I had actual people who were saving other people's lives like firefighters and nurses who were running out of masks."

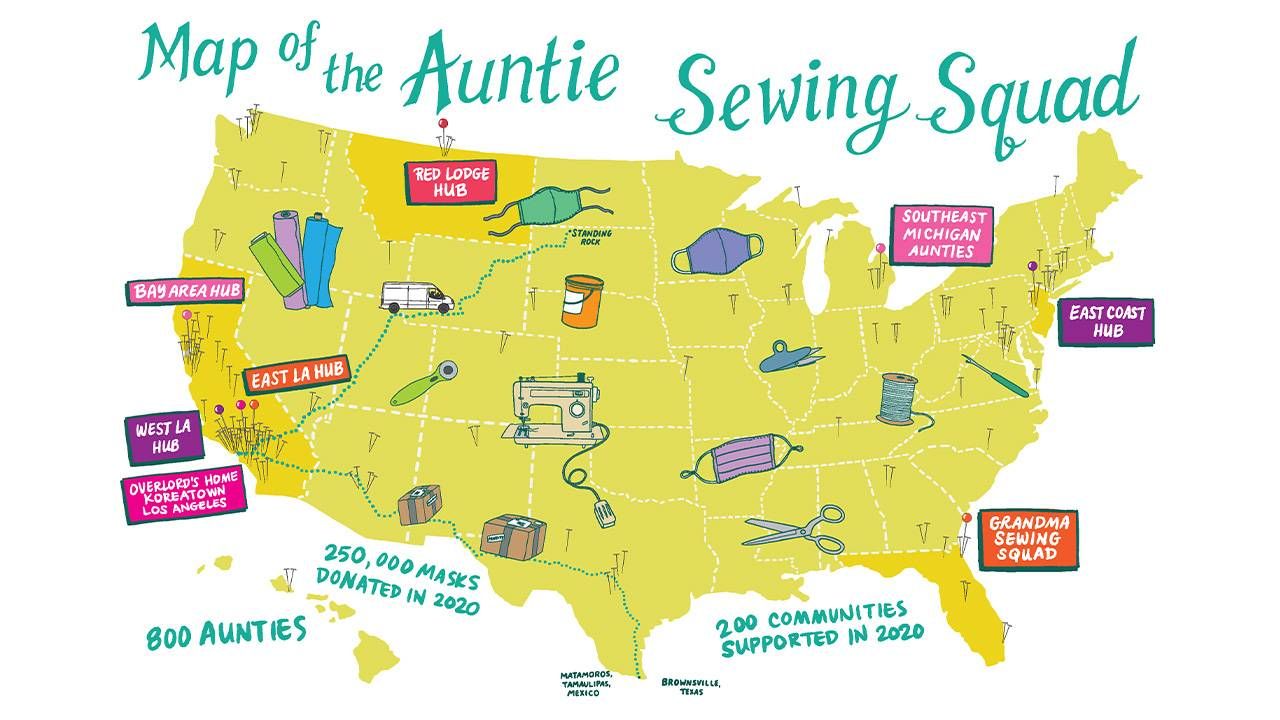

The Auntie Sewing Squad sent out more than 300,000 masks all across the United States.

As requests for two masks turned into four, then turned into hundreds, Wong realized she couldn't possibly keep up herself, so she started an informal Facebook group, asking for people who knew how to sew (or were willing to learn) and who wanted to help make masks for people who needed them.

Like requests for masks, the number of volunteers grew and grew until there were hundreds of people around the country, many of them Asian American women, calling themselves the Auntie Sewing Squad, with Wong using "Sweatshop Overlord" as her title. (In Asian culture, the word "auntie" is used as a sign of respect and affection.)

The Auntie Sewing Squad sent out more than 300,000 masks all across the United States.

Their Story Became a Book

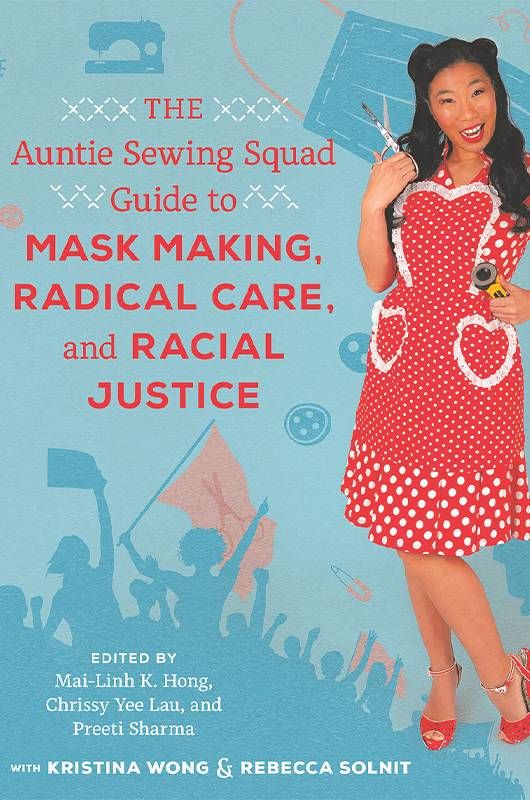

Now the group has put out a book, "The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice", with essays, drawings, photos, and patterns for masks, along with recipes for things like vegan kimchee, chocolate shortbread cookies, and a nourishing salve.

Edited by three California professors, Mai-Linh K. Hong, Chrissy Yee Lau, and Preeti Sharma, the topics include sewing masks for fun and no profit, ancestors, and sewing as care work. Wong, historian and writer Rebecca Solnit, and dozens of other Aunties contributed essays.

The book has received praise from a diverse group, including author Maxine Hong Kingston, comedian Margaret Cho and New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino.

The problem they faced, Wong says, along with the scarcity of materials to make masks, was how to get the masks to their destinations in places like rural areas or indigenous communities. This led to a system of "Super Aunties" making sure things would get to where they needed to go.

Wong, accustomed to writing grants from her years in theater, decided they needed some simple markers to track their progress, such as how many masks people needed, who they should be sent to or who would pick them up, and the date they were needed.

"We decided to just sort of lay out some conditions; [we wanted] people to stop for a second and name their needs instead of just passing their panic onto us," Wong said. "You have to set up a structure or everyone will feel helpless; it's just like people are yelling at me, 'Homeless people need masks!' That's not going to help."

The book came about, Wong says, because some academics in the group were interested in how the Auntie Sewing Squad fit into histories of immigration and sewing.

Interviews on Social Change and Asian American Women

One of the editors, Lau, didn't really sew herself before joining, but her grandmother worked for 30 years at a garment factory in Los Angeles' Chinatown. A history professor at California State University, Monterey Bay, Lau did an oral history project about the Squad, and more than 100 of her students interviewed dozens of Aunties, asking them about social change and Asian American women.

"They were in the driver's seat, determining the agenda and what [questions] were asked," she said about the students. "They were in awe of the Aunties and wanted to learn from them."

Lau says she loved working on the book with Hong, a professor of literature at University of California, Merced, who specializes in Asian American studies, race, and refugees, as well as Sharma, a professor of American studies at California State University, Long Beach, focusing on labor, gender, and immigration issues.

"I'm a historian by training, and I tend to work alone," Lau said. "I loved working with Mai-Linh and Preeti and talking about how sewing is connected to racial and ethnic issues."

Wong's friend Valerie Soe, a filmmaker, professor and an OG (original) Auntie, wrote the book's introduction, "We Go Down Sewing," with the editors.

Understanding the Auntie Phenomenon

Soe also made a short video, Radical Care: The Auntie Sewing Squad, asking the Aunties to send her clips she could put together since due to COVID she couldn't film them inside. And Soe's friend Solnit, who has previously written about mutual aid societies, introduced them to her editor at University of California Press.

"I want history to remember that we stepped up to do this. It felt like the labor of sewing is historically so invisible and undervalued."

"The book is amazing and in the collaborative spirit of the Auntie Sewing Squad," Soe said. "It's a fun snapshot of a moment with a scholarly framing, and I hope it helps people understand Auntie phenomenon."

"I think the books are wonderful — and I would think that even if I wasn't in it," said Vibrina Coronada, a theater artist in a small North Carolina town, who wrote an essay about being a Technical Assistance Auntie, using her skills with repairing sewing machines to help others.

"I bought a bunch of copies and sent it friends, and they really liked it. It's a nice antidote to how confined the pandemic has made life for some people," said Coronada." It's like the proverbial 'make lemonade out of lemons,' and I personally love lemonade."

Wong also created a show about the group, Kristina Wong: Sweatshop Overlord, which played off-Broadway in the fall of 2021 and ended up on several critics' Best Of lists. She says part of the impetus behind the show, like with the book, is wanting a record of what the group accomplished.

"I want history to remember that we stepped up to do this. It felt like the labor of sewing is historically so invisible and undervalued. This was sometimes reflected back to us in people saying something like, "Can you just sew up something like this for me?" It was like, "Uh, I know you are used to pressing two buttons and something shows up the next day, but that's not how this is going to work,'" Wong said.

She continued, "I wanted to educate people and remind them that we did this work, and we weren't just people who quietly clutched our pearls watching our family members be beat up in the street. We also are people who did solidarity work, and who really cared."