The Science Behind the COVID-19 Vaccines Could Be a Lifesaver for Melanoma Patients

One woman who's lived in the shadow of melanoma wants to know: Could this be just more false hope?

As the young nurse squeezed the syringe of Pfizer-BioNTech coronavirus vaccine into my freckled upper left arm in mid-April, I quietly hummed Happy Birthday.

"Sorry, that kind of tumbled out," I told her, slightly embarrassed about the unplanned serenade. "I just turned sixty and what a gift this is. We haven't celebrated the science of this extraordinary achievement enough."

She smiled and handed me my small white vaccination card after validating shot number two. I knew she was an oncology nurse, but our brief encounter at a Washington, D.C. hospital didn't allow a conversation as to why an mRNA jab — short for messenger ribonucleic acid — had so much promise beyond protection from COVID-19.

A Vial of False Hope?

Long before the pandemic highlighted mRNA vaccines in headlines, cancer researchers were experimenting with that same type of biotechnology to shrink tumors in patients with melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. While an mRNA cancer vaccine is not yet on the market, researchers' knowledge became an invaluable scientific foundation for mRNA coronavirus vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna.

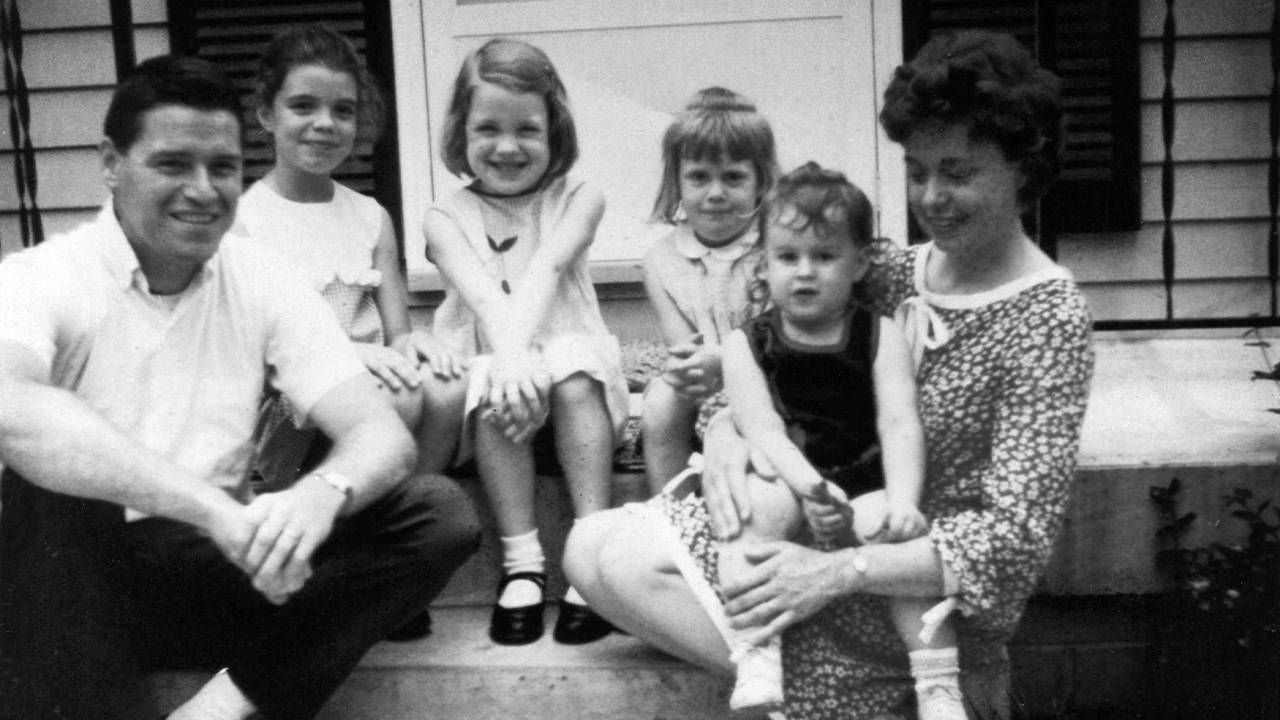

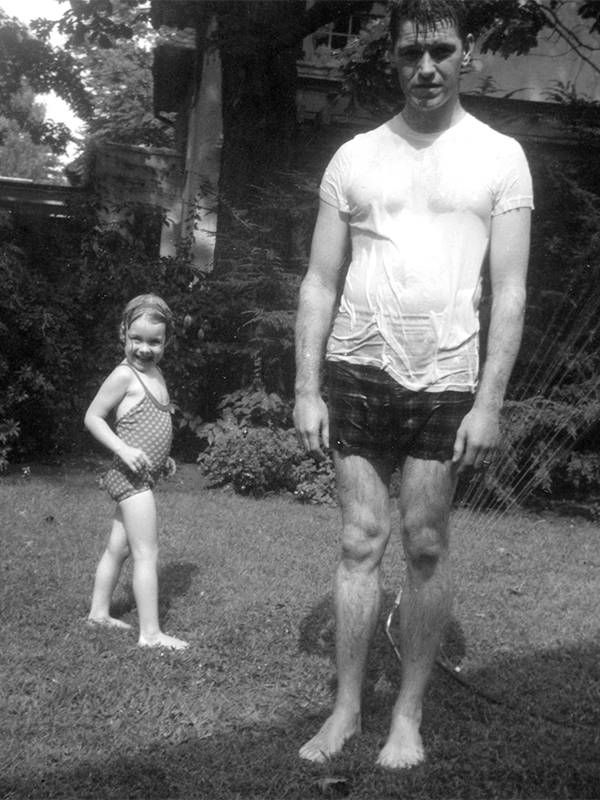

As a teen, I had watched melanoma kill my father at age 44 after he endured a series of surgeries and barbaric experimental treatments most of his adult life.

I paid close attention to those news snippets because I had grown up with melanoma. I found out how mRNA vaccines are also in the works for other cancers and infectious diseases such as malaria and various flus.

As a teen, I had watched melanoma kill my father at age 44 after he endured a series of surgeries and barbaric experimental treatments most of his adult life. No wonder I thought his fate was mine when I was first diagnosed in my early 20s.

Over the next 11 years, the melanoma spread from my skin to my lymph system, lungs, liver and beyond, before I was finally declared cancer-free more than two decades ago. Along the way, my doctor had advised against an experimental melanoma vaccine, not an mRNA type, fearing it might disrupt my immune system.

But with mRNA vaccines in the spotlight, what's the likelihood of one advancing beyond the early trial phase to treat, and even prevent, melanoma? Is that merely a vial of false hope, a solution for a tomorrow that never arrives?

Guardedly Optimistic

Dr. Nina Bhardwaj, director of immunotherapy at the Tisch Cancer Institute at New York City's Mount Sinai Hospital, said there's every reason to be optimistic, but guardedly so.

"It's a very exciting time. We have very interesting results coming in. We're learning a lot," she said, then adding in the next breath, "but I think we should be skeptical because of the long history of trying cancer vaccines."

A vaccine alone likely won't be enough.

In Bhardwaj's book, the next chapter will combine a vaccine with one or more of the four checkpoint inhibitors already greenlit to treat melanoma or other immunotherapies — some of which are still in the research pipeline. Inhibitors are immunotherapies that release a natural brake on an immune system so T-cells, the body's defenders, can recognize and attack tumors.

Bhardwaj lauded the mRNA coronavirus vaccines as "amazing, fantastic and extraordinary." Dr. Patrick Ott, who teaches at Harvard Medical School and directs the Melanoma Treatment Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, echoed those accolades.

Ott emphasized that large pharmaceutical companies could quickly pivot from cancer to the coronavirus because it had an identifiable target — the telltale spike protein. The human-made mRNA vaccine prompts humans to make the spike, recognize it as an invader and destroy it.

"The coronavirus genome was sequenced within a few weeks so they knew what to vaccinate against," Ott said. "A melanoma tumor is different because it's a cel,l not a virus. It arises from a melanocyte, which is a normal cell that becomes malignant."

While both doctors have spent years researching personalized melanoma vaccines that don't involve mRNA, they stay abreast of all relevant vaccine studies.

"For cancer, we don't know if mRNA is the best approach," Ott said. "Just because it worked for COVID doesn't mean we should drop everything else. But we can learn so much having watched the COVID vaccine develop. It was a lot of reality right in front of our eyes."

Why mRNA Cancer Vaccines Are Tricky

Every cell in our bodies already makes mRNA, genetic material that offers instructions on making proteins. Years ago, several dogged scientists figured mRNA could teach human cells to generate their own medicine.

Researchers have gravitated to melanoma for decades because the tumors have well-defined proteins for a vaccine to target. Cells damaged by ultraviolet light, which mutates their DNA, become tumors easily "seen" by the immune system.

"Pancreatic cancer, for instance, is not as identifiable by the immune system because unlike melanoma, it's not caused by an environmental assault on cells," explained Kristen Mueller, senior director of the science program at the Melanoma Research Alliance.

What's especially tricky about creating personalized vaccines for melanoma — whether deploying mRNA or another method — is that tumor mutations number in the thousands. Even though researchers now have speedier computer algorithms to sequence a specific tumor's DNA, choosing the right mix of mutations for a vaccine intended to stimulate a person's immune system to tackle a tumor is daunting, Ott said.

Today, about half of patients with advanced melanoma respond to — and are even cured by — an array of newer therapies approved by the Food & Drug Administration. That's a remarkable leap from 2007 when only 5% to 10% of patients responded.

Still, some of the more toxic immunotherapies can cause Type 1 diabetes, inflammation of the heart muscle and other permanent side effects, Mueller said.

What's especially tricky about creating personalized vaccines for melanoma — whether deploying mRNA or another method — is that tumor mutations number in the thousands.

An mRNA vaccine, or any vaccine for that matter, could be a boon for patients in early stages of melanoma and as an alternative to harsh therapies, she noted, because vaccines are extremely safe and side effects such as injection site pain and fever disappear quickly.

If a vaccine alone isn't enough, Mueller envisions a world where a vaccine could be administered to prevent melanoma, but also delivered directly into a patient's tumors with intravenous infusions of checkpoint inhibitors as a treatment regimen.

First, however, vaccine studies have to advance beyond phase one and two clinical trials, which are experimental and limited in size.

BioNTech, which collaborated with Pfizer on the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, has had notable success shrinking the tumors of patients with advanced melanoma in its early mRNA vaccine trials. In June, the German company announced the start of a phase two trial involving 120 patients.

Launching a phase three trial requires millions of dollars, hundreds of patients and FDA approval.

Nobody is there yet, but the pursuit is not slowing.

My spirited father, Ronald S. McGowan, was a willing guinea pig for pilot therapies, figuring any advance would eventually benefit somebody. In my mind's eye, I can picture a phase three trial coming to fruition — and him, with his sleeve rolled up, first in line.

Longtime energy and environment reporter Elizabeth H. McGowan is a Pulitzer Prize winner and the author of “Outpedaling ‘The Big C’: My Healing Cycle Across America," published in 2020 by Bancroft Press. She lives in Washington, D.C. Her Twitter is @ehmcgowanNEWS and you can visit her website: elizabethmcgowan-author.com Read More