What to Know About Microdosing

With psilocybin having a moment in American mainstream, it is worth considering the potential, anectodal benefits of microdosing

I live in one of the handfuls of American cities and states where psilocybin, though still federally banned, has been decriminalized and where the University of Washington Medical School, like many others across the country, has recently opened a center for research and study of this and other psychedelics.

Mushrooms are having more than a moment in the American mainstream and are being taken seriously as a treatment, if not a panacea, for many of the mental ills that trouble us.

But unfortunately, few studies focus on the risks or benefits of psychedelics for older adults, even though we, too, suffer from mental ills. Many of us are turning to them to delay the ones we worry about — waning cognitive powers, memory loss and even diagnosable dementia, to name a few.

Unfortunately, few studies focus on the risks or benefits of psychedelics for older adults, even though we, too, suffer from mental ills.

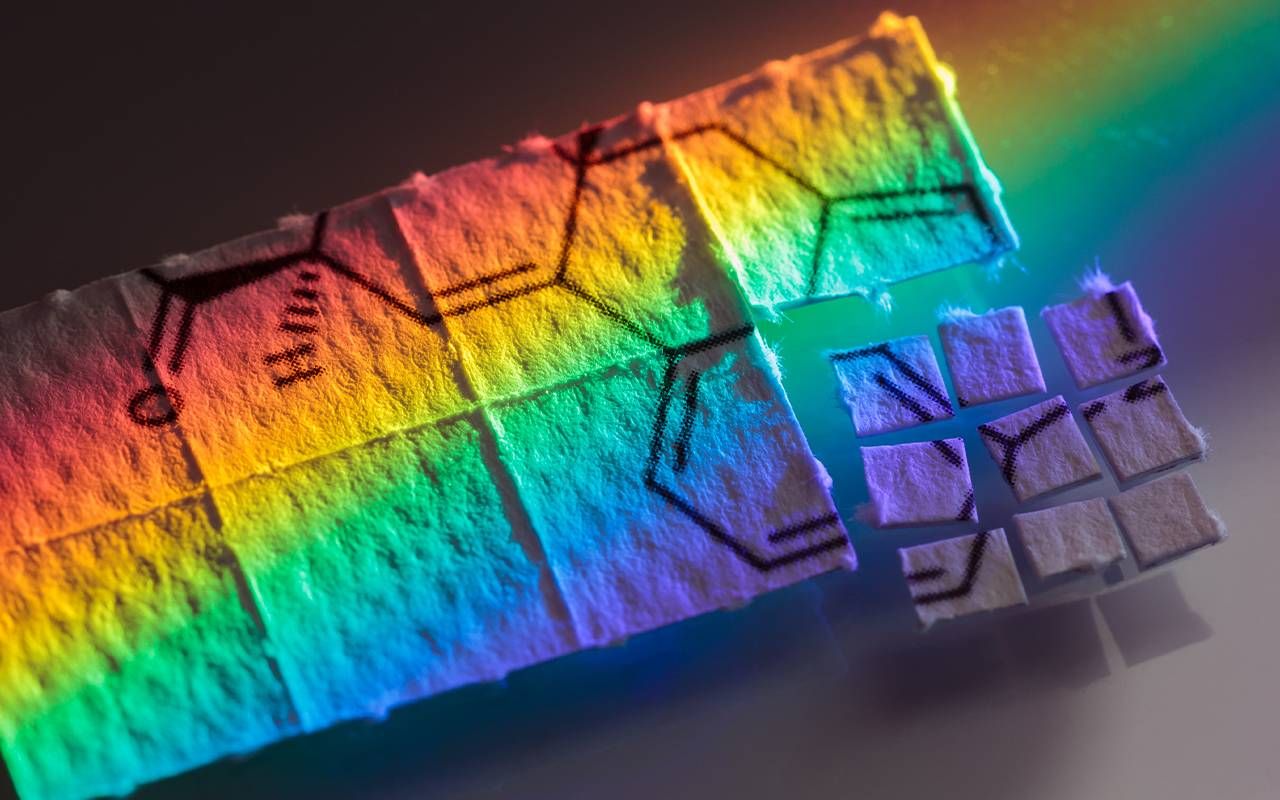

So, tuned in as we are by Michael Pollan's book and documentary, "How to Change Your Mind"; unsurprisingly, much of what we've been talking, reading, and hearing about is microdosing, which refers to a minute quantity of psilocybin or LSD taken regularly.

A microdose is measured in milligrams, akin to what in other substances might be considered a homeopathic amount, and the effect is sub-perceptual; a tripping dose, the kind that noticeably alters your perception, is 4 grams.

For a few who've begun taking what one friend calls her homeopathic medicine, on a regular schedule, the effect has been significant, while for others, it has been minimal.

So Far, Small Studies

Much of the early research into microdosing has been anecdotal. While laboratory studies tend to support claims of improvements in mood, attention, and creativity, these studies have generally been small, as the New York Times and other articles in the scholarly and popular press have pointed out.

Most studies didn't compare a microdose to a placebo, and none focused on older adults. However, a study reported in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry questioning the potential benefits of psychedelic medicines and related compounds for this age group said that they had shown promise in the treatment of a variety of conditions prevalent in older adults.

These include mood disorders, distress associated with a severe illness, end-of-life anxiety, PTSD, substance use disorders, and dementia.

While research suggests that psychedelics are relatively safe when given in controlled conditions, few older adults with some or many of these complaints have been included in clinical trials to date, making the generalization to them uncertain.

There is theoretical evidence to suggest that prolonged and repeated microdosing may cause valvular heart disease, and those with a history of cardiac disease are advised, even by doctors who support plant medicine, to avoid them.

On the other hand, psychedelics are potent 5HT-2A-R receptor agonists; this receptor is found in high concentrations in brain regions vulnerable to dementia, such as the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.

Psychedelics stimulate neurogenesis, restore brain plasticity and enhance functional neuronal connectivity; furthermore, all known genetic and environmental risk factors for Alzheimer's disease are associated with increased inflammation, and psychedelics have strong anti-inflammatory properties.

A Husband and Wife Try Microdosing

A thorough review of the science, especially studies conducted in the UK, convinced my long-time friend Michael to try microdosing himself and his wife, Anne. She was diagnosed a year and a half ago at 82 with Alzheimer's disease.

No placebo effect would influence her response to it, although it might color his; despite a successful career and a happy remarriage in his early 70s, his energy, creativity and motivation had begun to ebb even before his wife's diagnosis.

Psychedelics stimulate neurogenesis, restore brain plasticity and enhance functional neuronal connectivity.

He'd been managing Anne's medical care since then; although he told her what the 100 mg. capsule of psilocybin was that he added to her assortment of pills every other day, she didn't remember.

Microdoses of psychedelics have a sub-perceptual effect, with none of the visual distortions, hallucinations, or "trippy" results of a total dose, which, as stated, is generally 3 to 4 grams. Nevertheless, Michael was intrigued by what he read: "It can't hurt, and it might help," he said.

He was as objective as the scientist he is about his response as about hers, even accounting for the expectancy effect. After almost three months, he reports that using psilocybin every other day has resulted in observable improvement for both of them.

Michael, who weighs almost twice as much as his wife, takes a 250 mg. capsule, and while he doesn't compare it to a tripping dose, he has noticed a feeling of greater clarity and alertness soon after ingesting it.

The body begins to metabolize psilocybin immediately; in an hour or so, its effect is at its peak, and after three or four hours, most of the psychoactive compounds are out of the system.

"With my wife, microdosing seems to have slowed down the progression of her disease. As a result, she's much more alert, her energy level is higher and her attention span better," he said.

"There's not a big effect on her short-term memory; she might not remember that we discussed something an hour ago, but she'll remember that we did talk about it — just not when. And her long-term memory for people and events is excellent," he added.

A magic mushroom trip with slightly younger friends who've remained committed to their recreational use over the years was as much fun as it used to be.

For Michael, the results of microdosing have been more dramatic. "My mood and tone are much lighter, and after a long spell of being uninterested in writing or painting, my creativity is flourishing. I don't feel as bogged down as I used to; I feel, not high, but elevated," he says.

Since I've been writing about psychedelics, acquaintances and friends of friends have shared their experiences, concerns, and expectations. The local psychedelic community gatherings attract many elders who do likewise.

Some people I know who microdose report lessening anxiety, especially concerning their health or worries about their grown children and grandchildren. Others call it a tune-up for the brain: "Whenever I see those ads for Prevagen, I wonder if mushrooms are the hidden ingredient," a Facebook friend posts.

"I don't get knocked back by the bad stuff that happens, not how I used to," said one of a few people I know who've tapered off years of antidepressants and started microdosing instead.

Most people my age last tripped on psychedelics four or five decades ago. Back then, we were largely unaware of their medicinal properties, intent on letting them alter our every perception, heighten all our senses, and detach not only our observing ego from our consciousness but also any recognizable sense of time and space.

A Burst of Motivation

What remained in my memory of those long-ago trips besides how much pure fun they were was the extraordinary sense of connection I felt to the universe; it was as close to transcendence as I'd ever experienced.

I wondered if it was possible to recapture that cosmic consciousness. And at 82, would it be like a preview of coming attractions?

Well, not exactly. A magic mushroom trip with slightly younger friends who've remained committed to their recreational use over the years was as much fun as it used to be, and although I did feel connected to the universe, sometimes I think that way without drugs, too.

But tripping on a full dose didn't do much to lift me out of the same place Michael felt stuck in before he began microdosing. My creative gas tank was still empty; I lacked the motivation to finish my half-completed essays, go back to the memoir I had abandoned in a dusty folder, complete the online course I'd signed up for, or even wake up in the morning without any enthusiasm for the day ahead.

I wasn't clinically depressed, but I found it hard to get excited about things that used to give me pleasure. In short, I had "the dwindles," my phrase for that blah feeling of time passing me by. And in your 80s, every day counts — or should.

It's beneficial to my mood, motivation, creativity and enthusiasm.

Microdosing has changed all that. It's beneficial to my mood, motivation, creativity and enthusiasm. On days when I microdose 150 mg. capsules of psilocybin, I feel a wave rather than a burst of energy, a sense of lightness, a lifting of burdens I wasn't aware of carrying.

It is like having your hair in a ponytail for so long that when you take off the rubber band and shake it out, you realize how long you've had a low-grade headache. Of course, the effect wanes by the next day, but even then, I work, play, and socialize with renewed interest in the world around me and its people.

I have no hangover on non-dose days, but I'm still motivated to do what needs to be done to keep my professional and personal life functioning. My resilience was in short supply before I started microdosing, but now, even when the news is bad or the hits keep coming, the setbacks seem manageable and don't drain the pleasure out of every day.

I told my doctor about my new regimen at a recent visit, reporting that despite some painful symptoms and iffy lab results, I felt mentally and emotionally much better than I did the last time I saw her six months ago.

She was interested, curious, and non-judgmental; either I'm not her only microdosing patient, or she's aware that psilocybin is having a moment in Seattle and knows me well enough not to be surprised that I'm having one, too.

"Whatever plant medicine you're doing, it's doing well by you," she said, as close to approval as I need to keep doing it.