Mo Willems Wants You to Have Fun

The beloved children's book author-illustrator discusses 20 years of The Pigeon, his experience working for 'Sesame Street' and why art for art's sake is so critical

Though he'd been working in various artistic mediums for years, Mo Willems first entered the picture book landscape in 2003 with "Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus!," the story of a pushy bird who insists he has every right to take control of a motor vehicle. It was a book, Willems says, that was unlike anything he'd ever created before.

"All characters are planted," he tells Next Avenue. "They are little idea seeds and you put them in your notebook, which is a garden, and they grow. Some of them don't, and some of them are invasive, and some of them become the characters you hope them to be. The Pigeon was not one of those things. He just showed up one day, fully formed and angry that I was writing about other things, that I just wasn't focused on him."

This fully formed, temperamental "rat with wings," as Willems refers to him, became a massive hit. "Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus!" went on to receive the Caldecott Honor, considered one of the most prestigious awards for children's books, and was followed by seven additional Pigeon titles, which have sold more than six million copies combined in North America. Many of Willems' other works, including the "Elephant and Piggie" series and the "Knuffle Bunny" trilogy, have become bestsellers and award winners, as well.

"All characters are planted. They are little idea seeds and you put them in your notebook, which is a garden, and they grow."

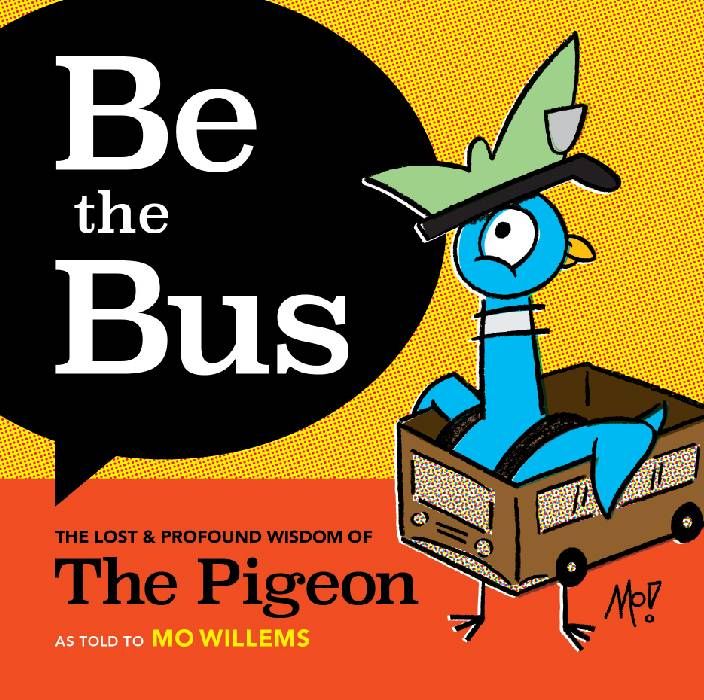

Now, he's releasing his first book aimed at adult audiences. The Pigeon turns 20 this year, and he's ready to share some advice. "Be the Bus: The Lost & Profound Wisdom of the Pigeon" aims to help young-at-heart readers ponder The Pigeon's take on life. Simultaneously, a special 20th anniversary of the original picture book will be published, featuring an exclusive board game.

With all of his work, Willems aspires to have — and encourage — fun. He prefers that his books be played, not just read, and he says his goal is to "spark readers to make or create for the fun of it." He recently spoke with Next Avenue about creativity, art making and why "Sesame Street" was his graduate school.

Congratulations on 20 years of The Pigeon! Where did the idea for this cranky character come from?

A long time ago, [my wife and I] took a month off and we moved to Oxford, England, where I had spent some time when I was young, and I decided I was going to write the great American picture book. I was going to be in this little house and sit in the garden and write every day. About halfway through the trip, this pigeon started showing up in my notebook, complaining that I wasn't writing about him. So, to placate him, I made a little sketchbook. At the time I was doing animated films and my production company was making these little sketchbooks, so more or less what the first book ["Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus!"] ended up being was this sketchbook, which I just thought was a gag book for clients and friends.

My wife was working as a school substitute teacher and librarian, and she started reading [the sketchbook] to kids. She was the one who was like, "This is a children's book that you made." To which I was like, "Pfft. No. You don't know what you're talking about." Obviously, she was right. So, it's really a weird thing. The pigeon bypassed a whole bunch of steps that I usually take when I'm creating a character and was both in design and personality pretty close to fully formed from the beginning.

What made you decide to write "Be the Bus," the new book of Pigeon-isms for adults?

The Pigeon is, for worse or for worse, somewhat part of my personality, and kids have now grown up with this pigeon. And this is the first book that The Pigeon is in any way cognizant of the fact that it's in a book. If you were to tell The Pigeon beforehand, "You are in books and people laugh at you," it would be shocking news for it. First of all, it'd be like, "I'm in books? These are tragedies! Every one of them ends poorly. I never get what I want! But now it turns out, children are laughing at me?!" The Pigeon would molt into nothingness. So here's the chance for The Pigeon to get some revenge and write what it thinks a book about The Pigeon should be.

Early on in your career, you worked for "Sesame Street." What did that experience teach you about writing for younger audiences?

It taught me that I wanted to do it. It took me a couple seasons. I was writing sketch comedy, and it took me a while to realize that what I like about writing for new people at the party [children] is that they don't know where the bathroom is, they don't know where the crudité is, they don't know where the keg is. So you get to write about fundamental things, which are essentially philosophy, love, hatred, jealousy, wanting to drive a bus — those core Greek values. If you're writing for adults, you're writing about the latest band or something in politics or news or celebrity, and it's all very ephemeral. And as someone who doesn't really watch enough pop culture, I couldn't keep up.

The other thing that was great at "Sesame Street" is — and I do recommend this for anybody who wants to write children's books — you learn so much and your name isn't on it. If I write a script that isn't great, the worst that a kid could say was, "Elmo wasn't as funny today." You could learn and discover and have a rhythm without your name on the cover, with all of the support of the other writers and the performers who knew how to make something work. You could also start to find your own voice in that space. So for me, it was going to graduate school.

The first time I read "Knuffle Bunny," I was so taken by the combination of drawings with photographs. How do you determine from series to series or book to book how you want it to look visually?

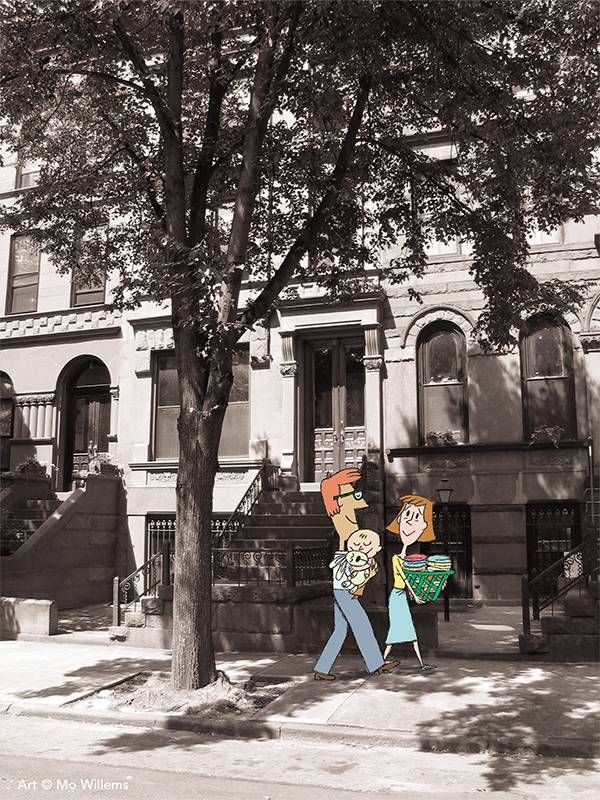

It's casting. Think about: you're casting your character, you're drawing them, you're figuring out what is the paper and what is the technique. With the "Knuffle Bunny" books, it's a small story. And the rule that it breaks is, usually a picture book is about a kid the age of the reader or a year or two older. This book is about a character that is a year or two younger than the intended audience. It is the first time that a child can have nostalgia and start to say, "What was I like when I was a kid?" So the physical format of the sculpture — I think of books as sculpture — is it's a photo album. The photographs are black and white because you are reminiscing. You're going back in time and you're turning the pages and looking at the photos. The whole thing invites you into a certain sort of space.

"I was happy to do the 'Lunch Doodles' because I believe that if I'm afraid, maybe other people are."

The key with that book was the amount of work taking objects out of the photographs, getting rid of all the air conditioning, all of the trash, all of the things that your eyes get rid of naturally, that when you see in a photograph they're somewhat shocking. I needed it to be emotionally true, more than visually true, and that was the trick. So every book, there's a reason for [the appearance]. The shape of the book, whether it's tall or big or wide, is all integrated into what the story is. You never know when it's right, but you definitely know when it's wrong, so you just do it until it stops being wrong.

Not long after you were named the first-ever Education Artist-in-Residence at the Kennedy Center, COVID-19 hit and you began hosting "Lunch Doodles" from your home studio. That series was so helpful to kids as well as parents; what impact did it have on you personally and on your work?

I was happy to do the "Lunch Doodles" because I believe that if I'm afraid, maybe other people are. It gave me a bit of solace and gave me some agency, because I think we all felt like we had no control. I did have a little bit of control; I would write this thing, and my son would shoot it, and my wife would help me and we would build props, and then we would shoot and then it would go on air. It was something that we did as a family, and being together as a family was very important at that time.

"I only choose things I know nothing about. There's a gleeful terror in it. I'm now working on my third opera. What do I know about opera? I know nothing about opera."

I started to see in a deeper way the balance between science and art and the value of art as solace. Not just looking at or experiencing art, but the making of it. I feel like we as a culture are discouraging art making unless it is a living-making. We don't discourage sport-making. We play basketball, we play kickball, we go running. Music is a physicalized form of emotion, sport is a physicalized form of understanding oneself, and drawing is a physicalized form of empathy, because you are thinking of what you are drawing. Even if it's a teapot, you are thinking about what is the teapottiness of that teapot.

So being able to draw and paint really became a solace. I started making very large-scale abstractions. Just the making was super great for me. And the idea that I could encourage the making to people who will not make a living at it, who don't aspire to that, but just [participate in] the joy of making and the power of that, that was really important to me and it became more so in that time.

So many of us are afraid to try new artistic things for that very reason you just mentioned — that unless it's for external validation, it's not worth it. For example, when I try to write fiction, I often quit because I'm afraid people won't like it. Do you have any advice on how to enjoy the process and not get bogged down with fears about the outcome?

If you are writing something, you are writing it for other people, absolutely, but you're not writing it for everybody. If I expected everybody to love this new Pigeon book, I'd be sorely disappointed. Sorely, sorely disappointed. It's okay! You don't have to love my work. That's not what it's about. There's power in the doing. If your kid is inclined to write a letter, or write a poem, or write silly lyrics, that's your opportunity to do a verse, as well. A part of what makes this easier is to do it in tandem.

We put out a big thing of butcher block paper every night on the dining room table. We have crayons, we draw every night. And we have family and friends who do not consider themselves artistically inclined and they say, "I can't draw." And we say, "You do not have a choice. This is not about whether you can or can't. Write a laundry list. Write your name over and over again. Do whatever." And by the end, everybody's drawing. There's no judgement, it's all going to be recycled. But the conversation flows through the drawing. You see [someone say], "I like the color you're using there. You know, I remember I once went to England and it was so green. It was like this crayon, only a little bit more so..." It becomes a larger thing.

You've worked in so many different artistic mediums, both on your own and through the residency at the Kennedy Center. Do you ever think, "I can't create art around dance or symphonic music. I know nothing about those subjects!"

Oh, yeah, that's why I do it! I only choose things I know nothing about. There's a gleeful terror in it. I'm now working on my third opera. What do I know about opera? I know nothing about opera. But, you know what? You go to someone who's a great opera singer and you say, "I know nothing about opera, except [that] opera is about big emotions and children's books are about big emotions. There's got to be a commonality there." And then we make opera. I don't see any point in trying to do something that I already know how to do. So the answer to your question, why [write] "Be the Bus"? Because I haven't done that before. That's enough reason.

What has been the most rewarding aspect of your career so far?

Hmm. [long pause] That I have one. [laughs] That I get to do these things. I get to play in all these different sandboxes. It really is remarkable. Often, I am doing something I have never done with people who are doing something they have never done. So I'm working on an opera with someone who's never done stuff for children, or I'm making a cartoon with actors who usually are on Broadway, and a trumpeter who does jazz and hip hop, but has never made kids cartoons. None of us have done it. That's exciting! That I get to have a career is a gift, and I certainly deeply appreciate that opportunity. And the idea that for whatever reason, people seem to say yes to these terrible ideas is just so great. I almost have a moral obligation to do them.

Read More