The Moment That Changed Mitch Albom’s Life

The author of ‘Tuesdays With Morrie’ reveals his own greatest life lesson

Imagine you're channel surfing when you suddenly recognize a familiar face on TV. It's your favorite professor from college, someone you haven't seen for many years. He's sharing the news that he's dying. That's exactly what happened one March night 22 years ago to Detroit sportswriter Mitch Albom. He was flipping around when he saw his mentor at Brandeis University, Morrie Schwartz, telling Ted Koppel on Nightline that he was dying of ALS, Lou Gehrig's disease. From that moment on, Albom's life would never be the same.

Albom was stunned. And horrified that 16 years earlier at his college graduation, Morrie — that's what everyone called him — had asked Albom to promise he would stay in touch and he had agreed. But as Albom wrote in his paper, The Detroit Free Press, “I broke that promise every day, week, month and year — for 16 years."

After processing what his sociology professor was saying — not just that he was facing death but that he wanted to share bits of wisdom on how to live ("Learn to forgive yourself and others"), Albom summoned up the courage to call Morrie. He then visited him on a Tuesday, then the Tuesday after that, and then weekly for the next six months as Morrie's disease progressed. To help pay Morrie’s medical bills, Albom wrote a slim book from their recorded conversations. Publisher after publisher rejected the book proposal.

Just weeks before Morrie died, Albom was able to give him the news that Tuesdays With Morrie was finally sold. Morrie didn't get a chance to read it before he died, but oh how his words have echoed around the globe.

Tuesdays With Morrie became the biggest-selling memoir in the history of publishing — 15 million copies worldwide. Schools teach the book and Morrie's lessons. It's been translated into some 45 languages, spawned an Oprah-produced made-for-TV movie and a play that continues to be staged around the globe. Morrie's younger son, Rob, a Tokyo-based journalist, has traveled around Asia doing Q & A's after its performances and says, "The response to the play in Asia — especially China — has been remarkable. People really seem to connect with Dad, despite the cultural divide."

On the 20th anniversary of Tuesdays With Morrie, appropriately a Tuesday, I asked Albom, 58, to reflect on reconnecting with Morrie and how his weekly visits to his dying professor changed the essence of who he is. Highlights from our conversation:

Next Avenue: Near the end of Tuesdays With Morrie, you wrote: 'I look back sometimes at the person I was before I rediscovered my old college professor. I want to talk to that person.' Who was that person?

Mitch Albom: Very driven. Very goal-oriented, ambitious, very much looking at every day as a commodity of hours to be utilized for my own betterment or advancement. If I could work seven days and that would yield something better than six days, there was no concern about what days I was giving up. I accepted every television request, every magazine request, every newspaper request, every freelance assignment — in addition to my regular job.

I spent very little time in any kind of meaningful conversation or relationships outside of my immediate family. They were very perfunctory and professional and always with a sense that there was endless time. Time was a commodity to be given away in exchange for advancement.

Twenty years have gone by since you wrote that if it were possible, 'you’d like to tell that person [the pre-1995 Mitch] what to look out for, what mistakes to avoid.'

I would say be careful how you give away your time. Even in well-meaning efforts, you can lose yourself in things that seem important or that are important to somebody else. You wake up later in life realizing you’re not only getting that time back, you don’t even have a reservoir of that time left. Ask yourself: If I commit to doing this, how much of my life am I going to have to end up devoting to doing it and what is that going to cost me in terms of what I could be doing elsewhere?

You’ve said one of the costs of being a workaholic before reconnecting with Morrie in 1995 was not making time to have children.

I would say that the joy of children, the majesty of children, has become much more apparent to me in these 20 years. I would have told myself not to be personally so afraid of the commitment of family. Pay better attention to what Morrie said about family. 'The fact is' he told me, 'there is no foundation, no secure ground, upon which people may stand today if it isn't the family.'

I remember writing that down, but never took it to heart in terms of the family you create. I took it to heart to the family you had. I was close with my family and I cherish my time with my existing brothers and sisters and my folks — my mom passed away. But the creation of a family is the single most important thing that anyone can do.

All the values that you aspire to in life. All the things you want to accomplish in your life, the lessons you want to teach other people in your life, the legacy you want to leave behind after you leave this Earth can all be done within the family that you create and continue to spread out to the rest of the world long after you’re gone.

Writing can be an egotistical profession, disguised in nobility. It’s not like being an action movie star where everyone knows it's kind of vacuous, but you’re still famous. You can be famous for writing books and have a lot of respect. But I’ve seen a lot of people throw themselves into books or projects with a message, determined to leave this message to the world in their work. And yet they don’t take the time to put that message into their own children.

And what I’ve learned is if you do it in children and they absorb what you have been trying to get across, you will have affected the world a lot more than if you have a book that sits on a library shelf for all time.

If you create three little human beings who really know the lessons you were trying to get into that book and really live them, and you think about the number of people they touch for the rest of their lives and they have their own family and they do the same, they’re going to reach a lot more than that book. And I didn’t know that back then. Biologically, it came too late for me and my wife to do anything about that within our own reproduction.

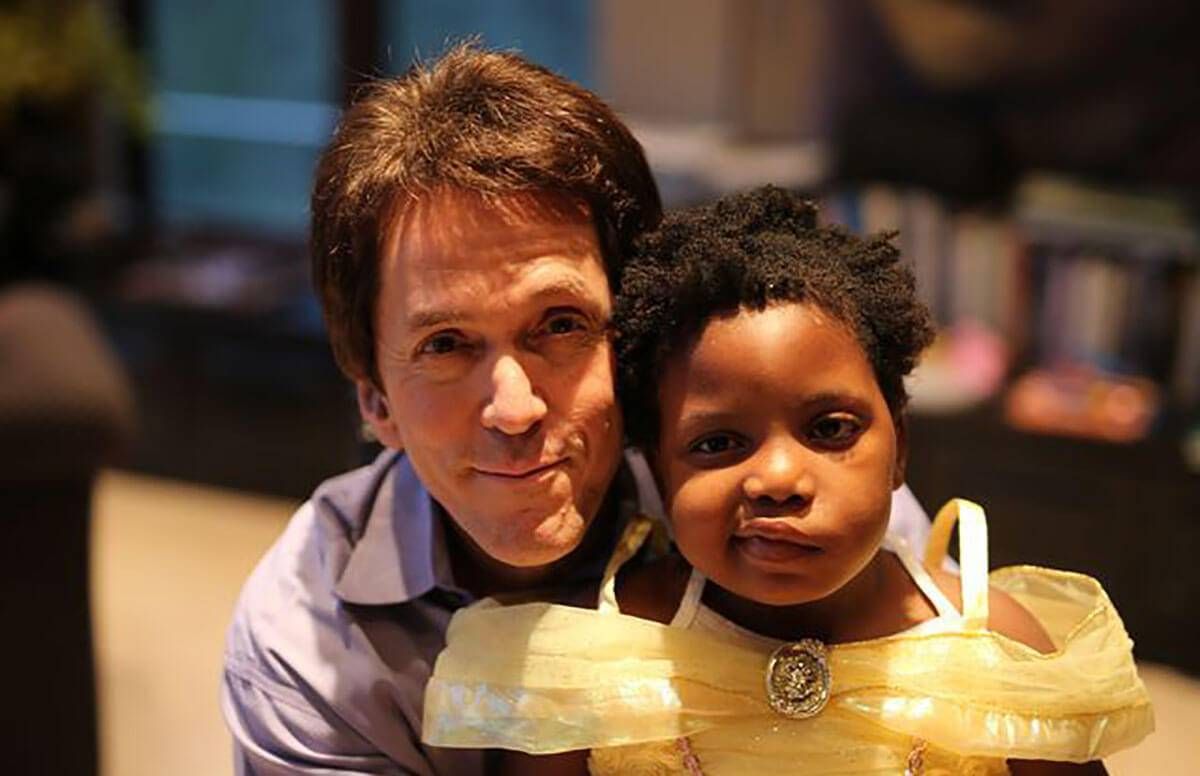

One of the many charitable works you've taken on since Morrie told you 'Giving makes me feel like I'm living' is an orphanage you founded in Haiti that you visit monthly.

I was given this huge blessing and huge opportunity. I cherish the time that I spend there and the learning these kids do and my ability now at this age to pass on lessons that I can watch them absorb. And I know that they will take that into their own life. And caring for Chika [a 7-year-old girl from the orphanage with a brain tumor] the last three years [at home], I’ve had a chance to be a parent to a little girl and to watch her grow. I cannot overemphasize how much differently I feel today about children being the saving grace of adult life than I did 20 years ago.

You write in the afterword that you’ve 'never felt so alive' since you began caring for Chika. She is your 'obsession.'

That’s true. Obviously she’s sick and that’s a whole different thing. I loved Morrie and I didn’t want to lose Morrie. It broke my heart when I knew I was seeing Morrie for the last time. But it wasn’t in my DNA or my mental capacity to throw myself on top of Morrie and say, 'No, no take me.' ... Morrie never asked me to protect him. Morrie never looked at me and said, 'Can’t you do something to get me out of this?'

Morrie was more concerned about leaving me with something — before I go, I want you to have this — which I totally understand now. With Chika, sometimes I look at her — even though she doesn’t speak anymore — I think I hear her saying to me: 'Can’t you do something to make this go away so I can play again? 'There’s not a more helpless and heartbreaking feeling than I have experienced in my life.

How often do you think about the odd events in life that had to come together to create the Morrie phenomenon that led you to change your outlook on life?

Every day. Every day in some capacity. Sometimes, it’s somebody who comes to talk to me and stops me and says, 'I read Tuesdays With Morrie' or I get a letter from a school that says, 'We’re writing essays.' You think: If I hadn’t turned the television on... How much of my day is spent on this thing?... A box of books arrives from Indochina with my name on it and some weird translation —Tuesdays With Morrie in a language I don’t understand.

Even when it’s not specifically about Tuesdays With Morrie, I think: 'Should I just go do this or should I not, whatever this might be? Should I drive myself down to talk to someone because I know this person is in hell?' I always push myself to do it because I think 'if you had not made that phone call to Morrie ...'

What about all the people who’ve never had a Morrie in their life, someone to inspire them. How does the average person become less self-absorbed and more attentive to the needs of others?

I’ll be blunt and honest. It’s a lot easier when you have a Morrie. They take you by the horns. And they force you to look at what’s important. The other way is harder. You have to do it on your own. It’s the difference between a running jump and standing still and jumping. In theory, they’re both jumps, but you get a lot more momentum if someone is pushing you or you have a life-changing event. You have a cancer scare, a near accident, you lose a job at the height of your career. These things force your eyes to be open.

If you don’t have that happen, look around at how many people do have that happen and pay close attention to how their thinking gets turned around. I’m 58 and am endlessly running into people who go from something that defined them — their career —and are let go 10 years shy of when they wanted to be let go and cannot find anything else to do. They are brilliant, accomplished people who are being told: you’re too old to be desirable and too young to die.

Now that has not happened to me — yet — but I have seen it happen enough to know there is no reason I’m going to be spared from that and I think that’s something people can do: develop a sensitivity to other people’s suffering and recognize it’s not just 'There but for the grace of God, go I.' But the odds eventually catch up with you.

Every day, Morrie would put a bluebird on his shoulder, that was his way of doing it. Every day you have the bluebird on your shoulder and you turn to the bluebird and you say, 'Is the day I’m going to die?' And you know that every day of your life but one, the bird is going to say 'no' and you think you can simply go on with your business but you can’t go on with your business because by forcing yourself to ask, 'Is this the day I'm going to die?' you're forcing yourself to think, 'Am I prepared for the Yes answer?' And if you can look at other people suffering and say, 'Am I prepared if that happened to me? What would I do?' you can adjust your life accordingly — you don’t have to have Morrie come tell you. You can just use the world as your Morrie.

The theme of your new afterword is Morrie's aphorism that 'Giving is living.' More than any of his other pearls of wisdom, is that the one you hope sticks with people?

It’s always a bit of a competition with Morrie when people say: 'What’s your favorite line?,' like it’s the Olympics — a gold medal, silver medal, I can’t really do that with all the wonderful philosophies he had. But I would say at the core of every single one of his thoughts was that giving is living. You’re most alive when you’re giving to someone else. He lived his life that way, and that’s why he was as happy as he was in his misery. I have found that to be true with Chika and other things. Yeah, If I had to pick a little sentence to sum up Morrie, that would be it.

A Different Afterward

Like Albom and millions of others, I, too, have benefited from Morrie's wisdom. I often wonder what might have happened if I hadn't been reading my hometown paper, The Boston Globe, on March 9, 1995. What if I hadn't noticed the headline: "A Professor’s Final Course: His Own Death."

I was senior producer of Nightline at the time. The story reminded me of a conversation I had one night after the show when Koppel gave me a ride home. He told me people in England, where he grew up, were more willing to talk openly about death than Americans, who seemed more reticent on the subject. and he had wanted to do a Nightline program on that phenomenon. So I showed him the story of Morrie Schwartz. He asked me to call him and see if he'd be willing to talk about his lessons learned over a lifetime. A bit reluctantly, Morrie agreed.

And Mitch Albom clicked his remote control at just the right time.

More than two decades after his death, Morrie's lessons continue to teach new generations.

Before he rediscovered his mentor, sportswriter Albom would be stopped at airports with people asking, "Who's going to win the Super Bowl?" Today, he says, he's gone "from being a 100-hour-a-week sports journalist to someone asked to speak at funerals, at hospice groups, at universities and at the bedside of dying patients." And today, the airport encounters often go like this: "My mother just died of from cancer and the last thing we did was read Tuesdays With Morrie together. Can I talk with you?"