How Muhammad Ali's Lessons Have Spanned Generations

In advance of the premiere of the PBS documentary 'Muhammad Ali,' former NFL great Reggie Williams and his son Julien, a martial arts trainer, reflect on Ali's echoing impact

How you react to the four-part documentary "Muhammad Ali," by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon, premiering Sunday September 19 on PBS (8 p.m. ET/7 p.m. CT) might hinge on your age.

If you're under 50, you might see it as akin to Ken Burns' past epics such as "The Civil War," "Baseball" and "Jazz" — a superbly crafted history lesson, but a bit distant. If, however, you are (like me) a boomer, it will be like your favorite classic rock albums.

As the tumultuous life of the most famous athlete of the 20th century unspools, each bout in and out of the ring may well remind you of where you were when the event was taking place. All the greatest hits, the jabs and the jabbering ("I am the greatest!"), will be like Proust's madeleine.

"I remember listening to his first fight against Liston on the radio under my covers."

Of all the boomer icons, there are two of whom it can be said changed everything: Elvis and Ali. In Ali's case, when he came on the scene, neither Blacks, nor athletes, nor especially Black athletes, were licensed to operate the way he did.

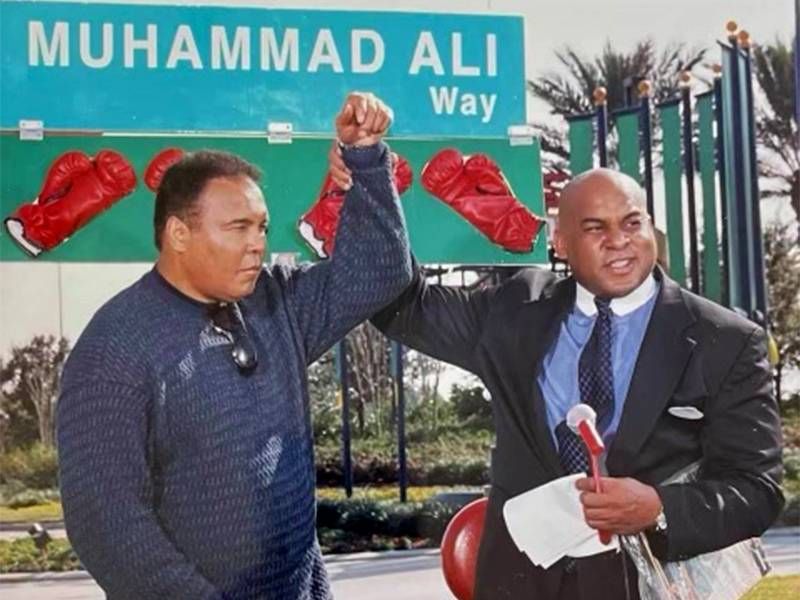

Reggie Williams will turn 67 on the day of the premiere. He grew up in Flint, Mich., became an All-America football player at Dartmouth, played 14 years as linebacker in the NFL for the Cincinnati Bengals, served as a Cincinnati City Councilman and oversaw the creation of Disney's Wide World of Sports complex in Orlando, Fla., whose entry street is named Muhammad Ali Way.

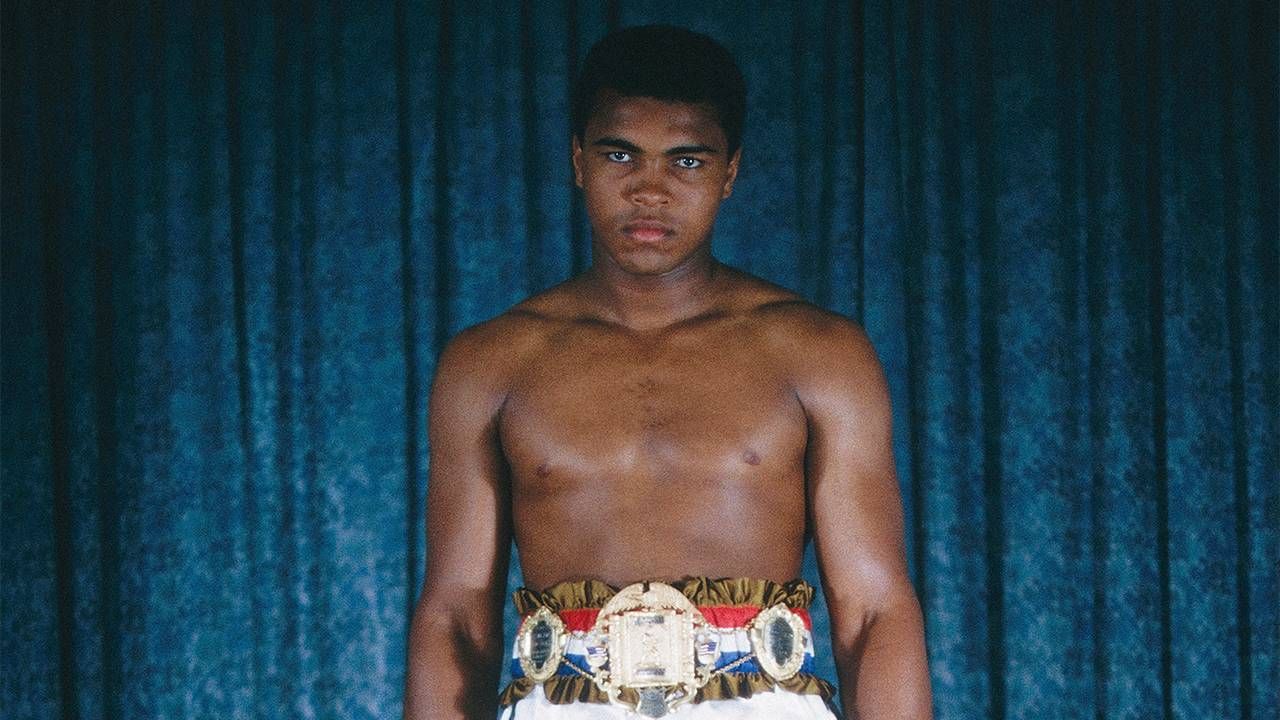

In 1960, when Williams, who is Black, was six, 18-year-old Cassius Clay burst out of Louisville, Ky. to dazzle as a light-heavyweight at the Rome Olympics.

"I remember the Rome Olympics," says Williams. "That's where I 'discovered' [Clay]. Or, that's where he discovered himself. He was absolutely my first hero."

Clay was dubbed "The Louisville Lip" by white sportswriters who didn't know what to make of him.

When a lean and hungry Cassius commenced his professional career, a ritual began among all of us youngsters that culminated in 1964 with Clay's upset victory over Sonny Liston that turned over the heavyweight title and, in Clay's own words, "shocked the world."

Says Williams, "I remember listening to his first fight against Liston on the radio under my covers." We all did. In those pre-ESPN days, that's how we had to consume our sports, which left much to our fevered imaginations.

The Most Polarizing Athlete in America

Quickly thereafter began in earnest the fighter's role as the most polarizing athlete in America. Becoming a Muslim, he changed his name to Muhammad Ali. You either loved him (as most young people did) or hated him (as most of our parents did).

He talked trash. With his versifying ("Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, rumble, young man, rumble!"), he was never less than entertaining, especially when he appeared on "ABC's Wide World of Sports" with his comedic foil, sportscaster Howard Cosell, another man who was loved and hated in equal measure.

"It was a great comedy act," says Williams. "Ali used to kid him about his toupee. He was the only one who could get away with stuff like that. Howard Cosell was a Jewish man who was very supportive of many of the Civil Rights efforts of Blacks. He and Ali sort of demonstrated a white person and a Black person getting along — having a sense of humor, having a rapport, to agree to disagree and still have fun."

During that era, the late '60s, Ali established several things. One, he was a hell of a fighter. He may or may not be the greatest of all time (Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis must also be in the discussion), but one thing is incontrovertible: He is the fastest great heavyweight of all time.

In his prime, no one could touch him. This comes through in all the old highlights, and even today's younger generation is dazzled by the footwork, especially the trademark "Ali Shuffle."

Reggie Williams' son Julien, 39, trains mixed martial arts fighters in Ocoee, Fla. Julien named his son Cassius: "My wife and I liked the name, but it's also an homage."

Julien is steeped in Ali lore. "My dad literally made me sit and watch 'When We Were Kings'" — the 1996 film about Ali's 1974 "Rumble in the Jungle" with George Foreman — "maybe ten times. I almost know it by heart."

As a professional, Julien can appraise Ali coolly and technically.

"My fighters study his ability to move, to be light on his feet," says Julien. "A lot of times, he had his hands down, which allows you to have better evasive movement. He was the best of the best at it. And he could still knock guys out. I still don't know how he applied so much power when he was moving. That's a skill you can't teach, really."

Likewise, his trademark showmanship.

"It is kind of a part of the job now, to have that showmanship," Julien adds.

A Man of Conscience

As Ali fought, bragged and entertained, he became a symbol for Black people worldwide.

"What was pivotal was the fact that he was so self-confident," says Reggie Williams. "And he was self-confident in saying 'I'm pretty.' That was so important for Black men and women back then. There were no commercials featuring Black people. America was not marketing to Black America."

In his biggest battle, Ali established was that he was a man of conscience. In 1966, at the height of the Vietnam War, he was drafted by the Army. Ali declared himself a conscientious objector and refused to be inducted.

"Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?" he famously declared, winning the hearts of many, Black and white, and the enmity of many others.

Convicted in 1967, he was sentenced to five years in prison; in every state, he was stripped of his boxing licenses. Four years later, the Supreme Court reversed the decision upon appeal.

"I was so impressed with his defiance of the military, refusing induction," says Reggie Williams. "This was a big issue for me. Because there was such fear at getting drafted, to be sent to a war in which I saw so many older kids in the neighborhood. If they came back, they came back with PTSD, they came back with injuries, they came back smoking dope, they came back with horror stories. And Muhammad Ali was standing up for his religious beliefs. But he was also standing up against Black people being sent over to Vietnam to die."

Without Ali, There Is No Colin Kaepernick

This became a critical part of the Ali legacy. Without Ali, there is no Colin Kaepernick (the former NFL player who is now a civil rights activist).

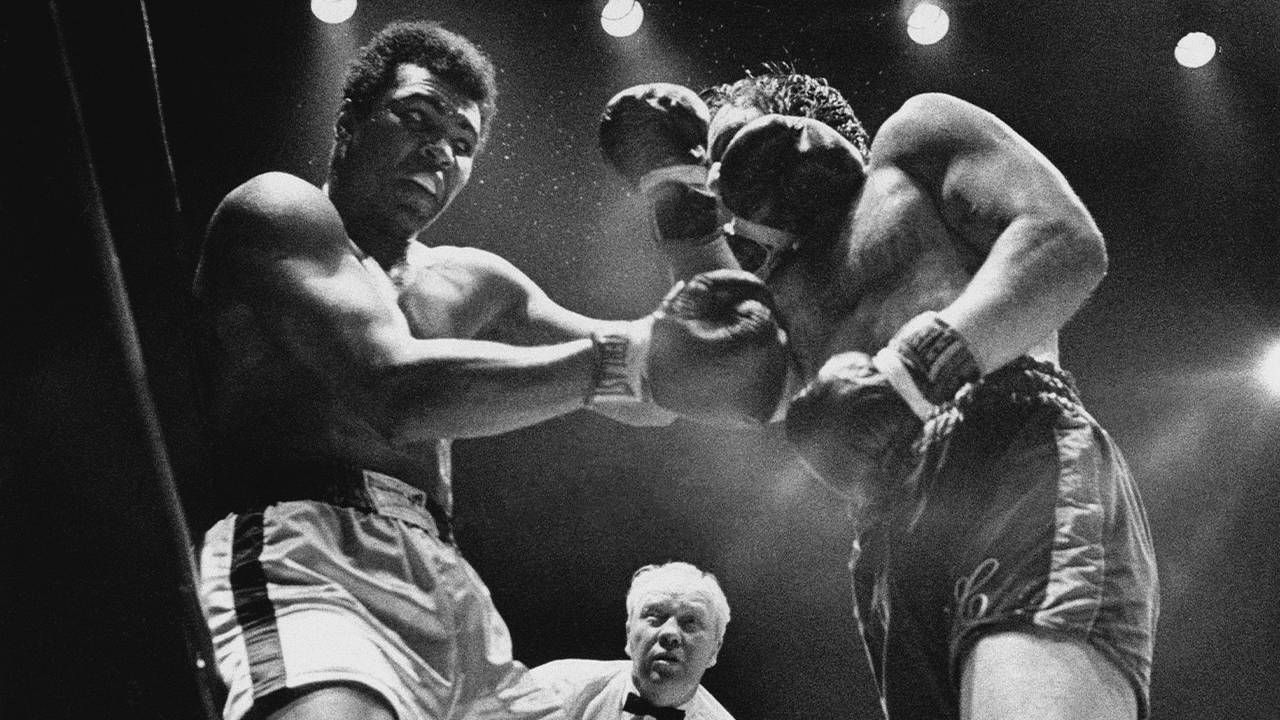

Ali was unable to obtain a license to box until 1970. Returning to the ring, he was rusty and had slowed just enough for champion Joe Frazier to be able to tag him with a sledgehammer left hook in their epic 1971 "Fight of the Century" at New York City's Madison Square Garden.

I was at a closed-circuit broadcast of the bout at Boston Garden, yet another way we were forced to get our boxing in those days. (Admission: $15.) And what amazed me was not that Ali got hit, but that he got up; any other human would have been dead.

I was a big Joe Frazier fan and when I exulted to one of my friends, a Black woman and an Ali fan, she responded bitterly, "That's what happens when you take away a man's livelihood for three years."

For the rest of his career, which ended in 1980, Ali took the pounding that no doubt contributed to his death from Parkinson's disease in 2016 at age 74. Of course, every time he got hit, he shook his head as if to say he wasn't hurt, when everyone knew he was.

"Now, when somebody gets hurt and they shake their head — then you know they're hurt," says Julien Williams.

"He told me to believe in myself. That's how you become a hero. Here was a champion telling me to be a champion."

As an elder statesman, Ali became a profile in courage and the most famous man in the world. (This is not to ignore his less edifying aspects, most notably his notorious womanizing.)

Everybody everywhere knew Ali.

"There was something I used to do at Dartmouth when I was on language study abroad in Mexico City," says Reggie Williams. "There were these huge plazas and there would be thousands and thousands of kids there. Every now and then when I would be really bored, I would get up on top of a concrete seat. I kind of looked like Ali — my 'fro was cut exactly like his. And I started doing the Ali Shuffle. Within seconds there would be this chant: 'Ali, Ali, Ali!' From total strangers in Mexico City!"

More crucially, Williams got to meet his idol on an airplane flight after college when he had played in postseason All-Star games but been dissed by a coach who told him an Ivy Leaguer never could make it in the NFL.

"I was just sitting there in tears," says Williams, "and there comes Muhammad Ali, walking down the aisle. I said, 'Wow, I gotta go talk to him.' And I walked up to him and introduced myself. And he was so encouraging. He told me to believe in myself. That's how you become a hero. Here was a champion telling me to be a champion."

Yes, kids, it was all as exhilarating, entertaining and enthralling as no doubt it will look in the documentary. I might even get under the covers and watch it on my smartphone.