My Father's Library

Looking for answers in the books that my dad is no longer healthy enough to read

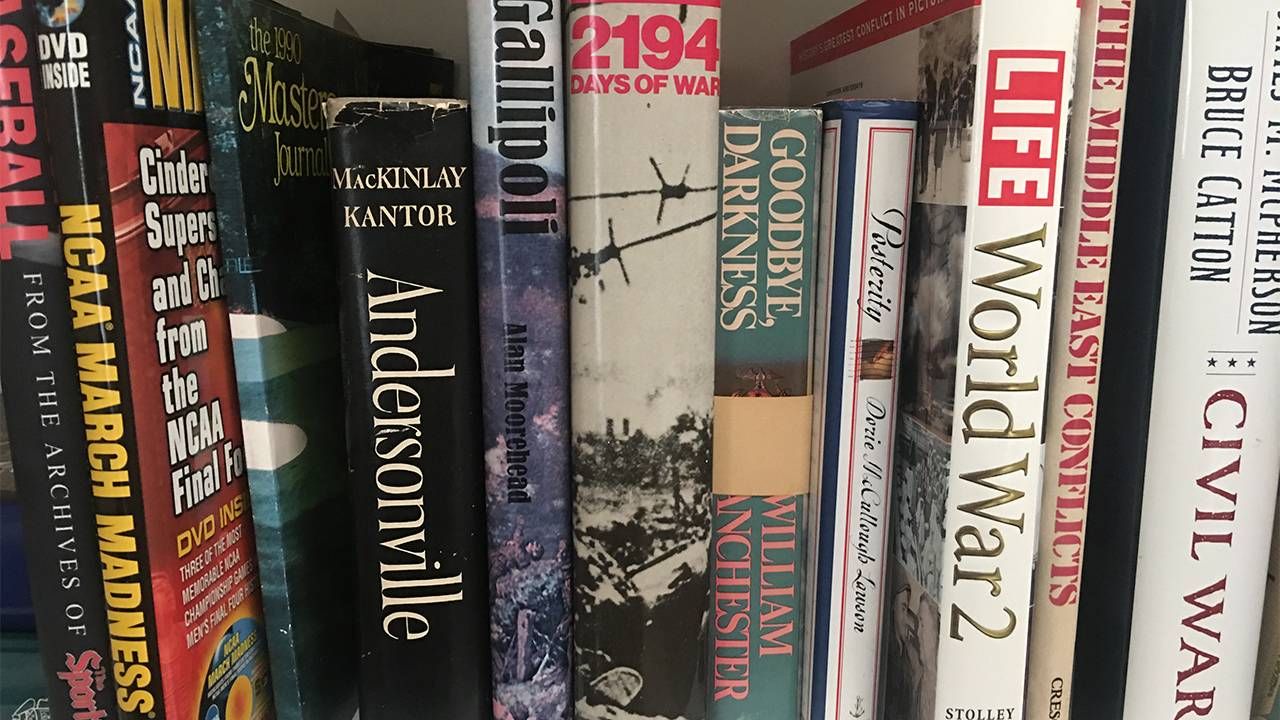

My dad's books cover an entire wall of the upstairs loft in his home in a 55-and-over community. The top two rows are arranged by author: James Michener, Alan Moorehead, Thomas Flanagan, Herman Wouk, plus a handful of old atlases and nonfiction works by David McCullough and Doris Kearns Goodwin.

The bottom row, which sits on a long, wide hutch, is lined with oversize coffeetable books that he picked up over a lifetime of browsing the bargain tables of Crown Books and Zern's, an indoor-outdoor flea market in Biglersville, Pa., where books shared vendor space with braided rugs, old beer steins and shoo-fly pies.

My dad, 83, owns so many coffeetable books he can't display them in the intended way, so most of them are visible only by their spines: "Gallipoli," "The Napoleonic Wars," "The History of the English Language," "Boxing's Greatest Fights" and "Sea Voyages that Changed the World."

These books I had barely glanced at as a kid suddenly became a window into the man who was fading from our grasp, a little bit each day.

There are also treasury-size compilations of Prince Valiant and Dick Tracy, "Andrew Wyeth: The Helga Pictures" and a still-in-plastic-wrap edition of "The Complete Cartoons of the New Yorker" from 2004.

One rainy day last fall, I found myself studying the books with atypical intensity. I had just spent the morning with my dad, and it was clear: He was no longer the father I had always known, the active pickleball-playing man who was ready to talk about the War of 1812 at 7 a.m. if you let him.

Two years of dialysis, coupled with a wide range of treatments for back pain and seizures, had taken their toll on his body and brain. Most disturbingly, he was no longer able to focus on the books that had shaped, comforted and engaged him most of his life.

'Mall Books' and Much More

These books I had barely glanced at as a kid suddenly became a window into the man who was fading from our grasp, a little bit each day.

The books in front of me were his favorites, the ones that made the cut when he and my mom downsized 15 years ago and he had to reduce his collection by a third.

He had paperbacks too, but they were deemed unfit to show off and always hidden in cabinets or closets. He called them his "mall books," lightweight books he could pull out of his pocket when my mom ducked into a store to browse or when he had to wait for a baseball game to start or a chair to open up at the barbershop.

My dad never left the house without a book. He did the bulk of his reading on his daily train commute to Philadelphia. Once, the train broke down between stations and passengers were stuck in their seats for hours. He had no reading material that day, and it lives on in family lore as one of the worst days of my father's life.

His briefcases took a beating and had to be replaced regularly -- less from work documents than from the weight of James Michener's latest 1,000-page novel.

Besides being an enthusiastic reader, my dad was also an avid note taker. He kept notes, in his broad Catholic-school cursive, on everything from doctor's appointments to road trips he and my mom took to Nova Scotia, the Grand Canyon and other destinations.

He also jotted down things as they occurred to him on scraps of paper and tucked them into whatever book he was reading at the time: topics to broach with his grandkids the next time he spoke with them, old Sports Illustrated issues he wanted to add to his collection, a list of all the U.S. presidents on a lined yellow piece of paper.

Sometimes he placed random newspaper articles between the pages: There was one about a cinnamon bun sale at a local senior center, another about the 1951-52 basketball team at La Salle College, his alma mater.

My father also kept an annual log of the books he read. Between 1972 and 2016, he read 1,076 books, an average of 24 per year.

His peak year was 2004, which topped 40 books and was wide in scope: "To the Heart of the Nile" by Pat Shipman, "The Shelters of Stone" by Jean Auel, "The Pigeon Project" by Irving Wallace, "Saddam Hussein: The Politics of Revenge by Said K. Aburish, "Violets Are Blue" by James Patterson, "The Perfect Storm" by Sebastian Junger and "Disasters Illustrated: Two Hundred Years of American Misfortune" by Woody Gelman.

Questions I Regretted Not Asking Sooner

My dad's book list stops at 2016. And, as far as I can tell, his notes and articles end about a year after that. That was when his health issues ramped up and my parents jumped on the treadmill of doctor's visits, medicine adjustments and days that were measured by pain intensity.

Realizing this felt like I had entered a classroom that had been shut down abruptly last year in a coronavirus-propelled frenzy -- science projects half-completed, pencil boxes left open on desks, St. Patrick's Day decor still hanging on walls. Wistful reminders of another time and the unsettling feeling of not knowing when, or if, that time will ever be fully recaptured.

Now it is my mom who seeks comfort in a good book after a day of taking care of my dad.

As I studied my dad's books, so many questions surfaced that I regretted not asking him sooner.

How did the son of a Whitman's Candies shift supervisor discover the Australian-born author and historian Alan Moorehead? Was there a particular book or author that caused him to pivot from a kid obsessed with comic books to a more serious reader? Why did he pursue a career in human resources rather than one that capitalized on his obvious love of history?

My Mom's Reading Habits

I'm not sure if I will ever get the answers. For the last year or so, my dad has stuck to reading newspaper and magazine articles. Even his "mall books" can't hold his attention.

My mom and I recently encouraged him to try reading Carl Hiassen's "The Downhill Lie," a humorous take on golf, his favorite sport. He took the book willingly enough, but gave it back to me the next day with a "thank you" and a shake of his head. In a year of sad moments, this was among the hardest to stomach.

Unlike my dad, my mom has never felt the need to surround herself with her favorite books. She prefers to patronize the library bookmobile, a reconfigured school bus that travels to outer areas of the county and parks outside the local Kohl's store every couple of weeks. She often relies on the reading suggestions of the bus librarian, with whom she has become friendly over the years.

Now it is my mom who seeks comfort in a good book after a day of taking care of my dad. It helps her leave behind the tedium and challenges of home dialysis, as well as the exasperation and sadness that comes with watching your spouse of 54 years forget rituals like birthday cakes and good-morning kisses.

It is heartbreaking to see my mom reading upright in bed while my dad sleeps deeply next to the whirring machine that keeps him alive, yet it lifts me up at the same time. Whatever the genre or page count, books have a remarkable way of soothing in so many ways, at all different stages of life.

Read More